The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Scientist on hike discovers organism so unusual it sits on new 'major branch' of tree of life

'There's nothing we know that's closely related to them,' biology professor says

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A scientist on a hike in the Canadian woods has discovered an organism that appears to sit on a new “major branch” of the evolutionary tree of life.

Two species of the microscopic creatures, called hemimastigotes, were found in earth collected in Nova Scotia by Dalhousie University graduate student Yana Eglit.

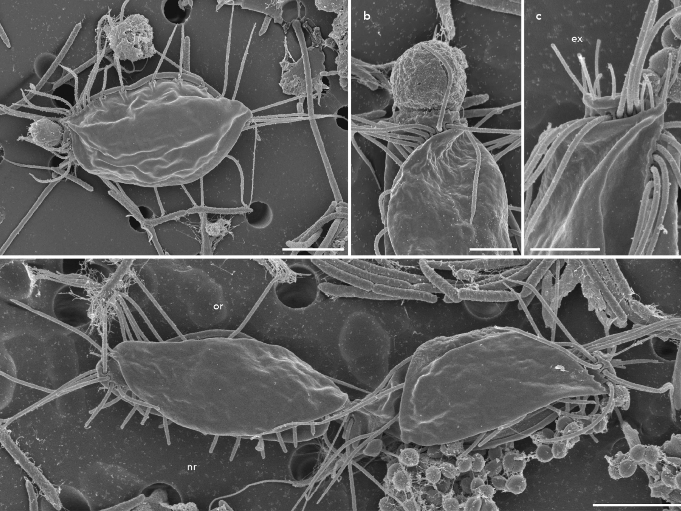

Unlike anything found in the animal or plant world, single-celled hemimastigotes are about two-hundredths of a millimetre in length, and scuttle around using a dozen or more hairs - known as flagellas - that stick out either side of it.

They were first described in the 19th century, but have remained, until now, a “tantalizing mystery” due to the inability of scientists to figure out which kingdom the creatures belong to, Ms Eglit told CBC News.

Like animals, plants, funghi and amoeba, hemimastigotes belong to a domain of organisms called eukaryotes, which all consist of cells in which DNA in the form of chromosomes is contained within a distinct nucleus.

But unlike other microscopic organisms, hemimastigotes move their flagella in an apparently random manner, rather than co-ordinated waves.

An advanced genetic analysis run by a team at Dalhousie University shows they are more different from other organisms than animals and funghi are from each other, for example, and represent an early new branch on the tree of life.

"They represent a major branch… that we didn't know we were missing," said Alastair Simpson, Dalhousie biology professor and co-author of a study on the organisms published in Nature.

He estimates the organisms have no common ancestors with any other living thing in the last billion years. "There's nothing we know that's closely related to them,” he added.

Described as “voracious little ogres” by the Dalhousie University research team, the organism - which "looks like a pistachio nut," according to Mr Simpson - catches other microscopic creatures using a “harpoon system” at the front of the cell, or by using its flagella to grasp its prey.

Ms Eglit discovered the rare creatures after soaking in water dirt she had picked up along the Bluff Wilderness Trail. Over the next few weeks, she checked to see if the water had revived any dormant microbes.

It had – she found two different types of hemimastigote in the soil, one of which was an entirely new species.

Once she worked out its diet, which includes a microbe called Spumella, Ms Eglit began to breed the new species, which the team named Hemimastix kukwesjijk.

The breeding programme will allow scientists to do a more complete genetic analysis of the organism, and to work out more precisely where it fits into earth’s evolutionary past.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments