Neanderthals lived alongside humans for centuries, latest study shows

How our closest cousins met their demise in Belgium

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Belgium holds the secret to producing some of the finest chocolate, waffles and beer in the world but it turns out the country may also have the answer to where the last Neanderthals died out.

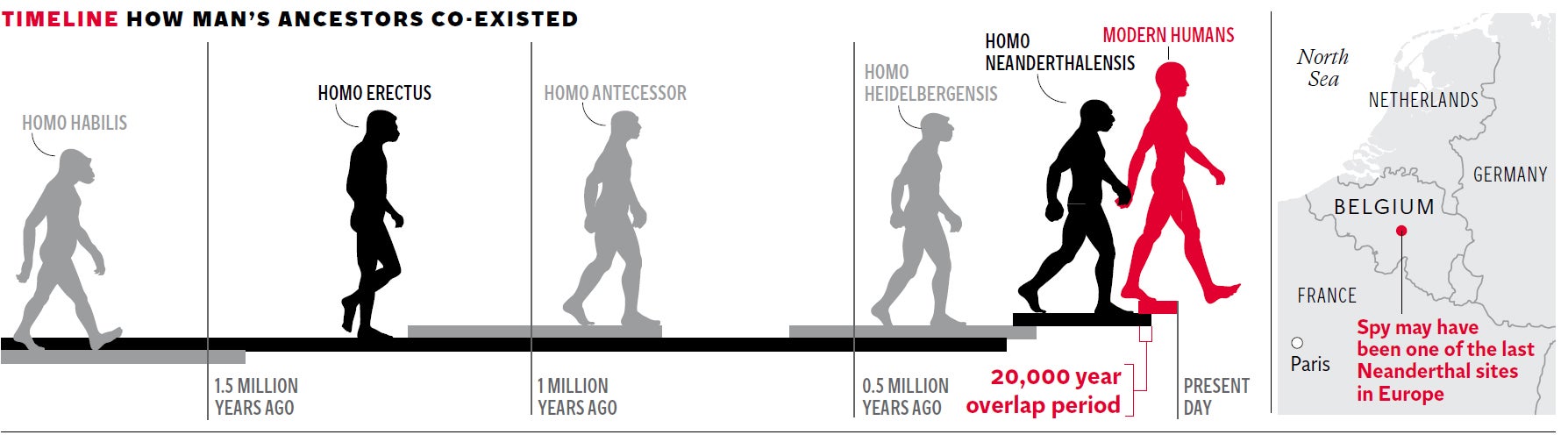

The latest and most precise date for when Neanderthals finally disappeared shows that the last time they walked the earth was 40,000 years ago, and they probably went extinct in Western Europe.

This means that they would have lived alongside anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens, for as long as 20,000 years, giving ample time for the exchange of culture and genes, scientists said.

How and when the Neanderthals – close cousins of H. sapiens – died out have been two of the great mysteries of evolution, but a new set of radiocarbon dates of Neanderthal bones and artefacts has finally solved the latter.

Scientists have analysed 196 samples of bone, charcoal and shell from 40 key Neanderthal sites from Spain to Russia and concluded that this species of thick-set humans who adapted to cold climates disappeared throughout this entire region before 39,000 years ago.

This means that the overlap in Europe with the newly arrived Homo sapiens, with their more gracile anatomy and more complex stone and bone tools, must have lasted at least 4,000 years.

It could have been as long as 20,000 years in Asia, which anatomically modern humans had colonised long before reaching Europe.

Previous studies have suggested that Neanderthals, which first emerged in Eurasia about 250,000 years ago, quickly died out when H. sapiens appeared, suggesting intense competition for resources and even violent conflict, culminating in a “last-stand” in southern Spain.

However, more recent studies have found that there was a degree of genetic mixing and interbreeding between the two strands of humanity, especially in Asia, although this did not extend to a compete assimilation of the two.

The latest study produced the first accurate dates for the final decline of the Neanderthals with the help of sophisticated developments in radio-carbon dating. It found a clear overlap within Europe that spanned some 25 to 250 generations – between 470 and 4,900 years depending on the region.

The overlap also fits with archaeological data on the kind of tools that each used, suggesting a period when Neanderthals began to copy the more sophisticated tool-making of the new migrants.

“We believe we now have the first robust timeline that sheds new light on some of the key questions around the possible interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans,” said Professor Tom Higham of Oxford University, lead author of the study published in the journal Nature.

“The chronology also pinpoints the timing of the Neanderthals’ disappearance, and suggests they may have survived in dwindling populations in pockets of Europe before they became extinct,” Professor Higham said.

Click HERE for full-size version of graphic

A cave system near Spy in Belgium, rather than caves in Spain, may be one of the last sites in Europe for Neanderthals to have lived, although it is still too early to say this for sure, he said.

However, Professor Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, said that the new analysis did not extend to eastern Neanderthal sites in Uzbekistan and Siberia – meaning it is possible that the species still survived in these enclaves for longer than in Europe.

“But the overall pattern seems clear. The Neanderthals had largely, and perhaps entirely, vanished from their known range by 39,000 years ago,” Professor Stringer said.

The demise coincided with a change in the climate to colder, drier conditions, he added. “It remains to be seen whether that event delivered the coup de grace to a Neanderthal population that was already low in numbers and genetic diversity, and trying to cope with the economic competition from incoming groups of H. sapiens,” he said.

Making history: carbon dating

The new dating technique eliminates the problem of contaminating carbon in archaeological artefacts. It uses a filtration system that eliminates particles from earlier periods in history that may have settled within the samples being analysed.

This has shown that some previous radiocarbon dates have been inaccurate, suggesting a long overlap between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens that did not actually occur, Professor Tom Higham said.

For instance, previous dates of Neanderthal fossils found at Zafarraya in southern Spain suggested they were 33,000 years old, which would mean several thousand years of overlap with modern humans – who were known to have appeared here about 40,000 years ago.

However, the actual dates of the Neanderthal fossils at Zafarraya are more than 47,000 years old, calling into question whether there was any overlap at all with modern humans at this site.

“Previous radiocarbon dates have often underestimated the age of samples because the organic matter was contaminated with modern particles,” Professor Higham said. “We used ultrafiltration methods which purify the extracted collagen from bone, to avoid the risk of modern contamination.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments