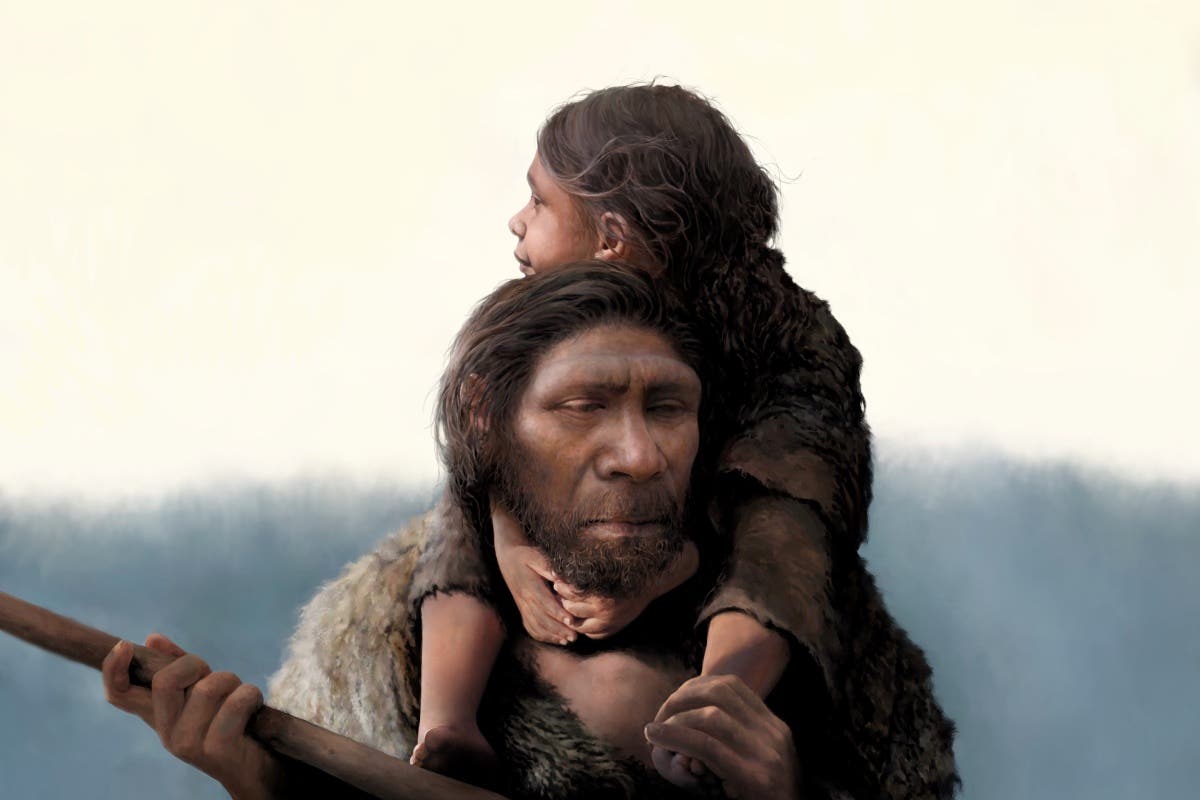

Neanderthal women ‘left home to be with their partners while men stayed put’

Around 60% of females are likely to have migrated to join their mates, DNA analysis suggests.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Neanderthal women, who lived in the Siberian mountains around 54,000 years ago, left their homes to join their partners in other communities while the men stayed local, research suggests.

DNA analysis suggests around 60% or more females who lived in the Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov Caves in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, Russia, moved to be with their mates, thus creating a connection between these small localities.

The researchers said their findings, published in the journal Nature, helps shed light on to the social structures of man’s closest extinct relative.

Dr Benjamin Peter, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, who is one of the authors on the study, said: “Our study provides a concrete picture of what a Neandertal community may have looked like.

“It makes Neandertals seem much more human to me.”

In what is thought to be the largest genetic study of Neanderthals reported to date, the researchers analysed data from the remains of 11 Neanderthals from Chagyrskaya Cave and two from Okladnikov Cave.

The remains show seven males and six females, of which eight were adults and five were children and young adolescents.

The researchers found that within these Neanderthal communities, the genetic diversity of Y chromosomes – which is passed down the male line – was a lot lower than that of the mitochondrial DNA – which is passed from mothers.

According to the team, this suggests that women were more likely to leave their homes than men.

The authors believe that within these small communities – comprising between 10 and 30 individuals per group – around 60% of females are likely to have migrated to join their partners.

The researchers also found that some Chagyrskaya individuals were closely related, including a father and his teenage daughter, along with a pair of second-degree relatives – perhaps a cousin, aunt or grandmother.

Analysis suggests some of them may have lived around the same time.

Another finding described “striking” by the researchers is the extremely low genetic diversity within this Neandertal community – which is usually seen in endangered species at the verge of extinction.

However, the authors cautioned that the sample size is small and further research is required to shed more light on the social lives of these people.

Neanderthals, or Homo neanderthalensis, lived across Europe and south west and central Asia between about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago.

According to the researchers, the Neandertals at Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov caves hunted ibex, horses, bison and other animals that migrated through the river valleys that the caves overlook.

They collected raw materials for their stone tools dozens of kilometres away.

Other materials seen at both caves also supports the genetic data that the groups inhabiting these localities were closely linked, the researchers said.