NASA astronaut Scott Kelly's year-long space trip is a rehearsal for Mars

As ISS astronauts return to a battery of tests, NASA is gathering data for even longer trips

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After the best part of a year in space and a re-entry which subjected his body to more than four times gravity’s earthly pull after 340 days of weightlessness, Scott Kelly might have been forgiven for wanting a hard-earned rest.

But within minutes of a blackened Soyuz capsule carrying him and two Russian colleagues from the International Space Station (ISS) landing on the icy steppe of Kazakhstan, the NASA astronaut was ushered into a tent and made to run around an obstacle course.

Commander Kelly explained: “We go through about an hour of field tests of various kinds - one is even like an obstacle course, where you run around, stand up from a sitting position and jump.”

Such is life when, as one of his colleagues at America’s space agency put it, your role is to be a “living, breathing, walking medical specimen”.

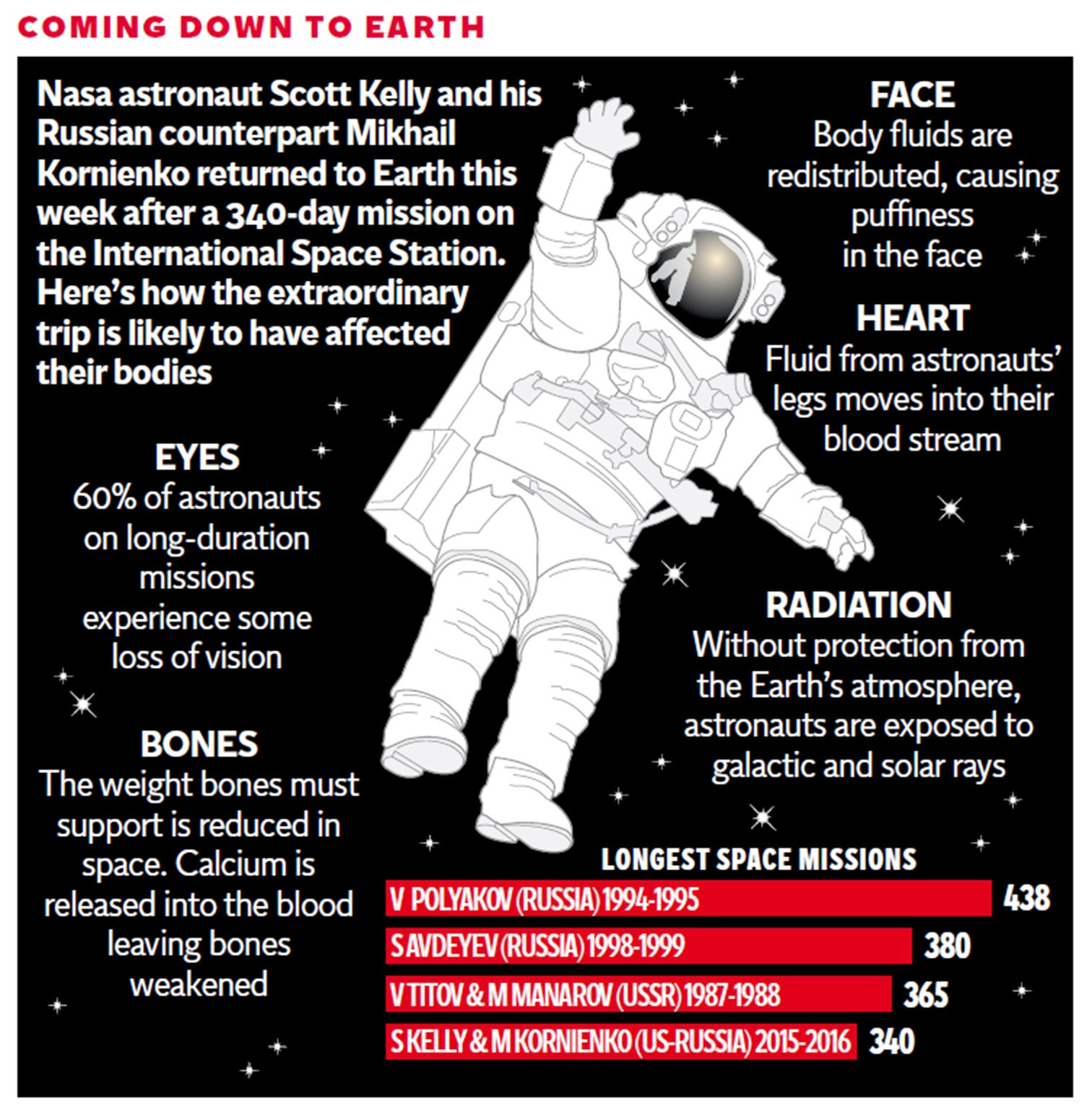

Kelly returned to Earth in the early hours after the longest stay in space by an American (the overall record of 437 days is held by Russian Valeri Polyakov) which encompassed both routine cosmos-based duties - fixing ammonia cooling systems and routing cables for docking ports - and a very particular role as a guinea pig for humanity’s eventual effort to reach Mars.

The 52-year-old and his Russian colleague, Mikhail Kornienko, had been the subject of dozens of medical and scientific experiments during their stay on the ISS to further examine how the body responds to weightlessness and being bombarded with radiation while some 270 miles above Earth.

The research, which includes a unique comparative study between Kelly and his earthbound identical twin brother Mark, also a former astronaut, is designed to help NASA prepare for the physical and psychological demands that will be made of the crew of a Mars mission that would last an estimated 30 months. The American space agency has set the 2030s as the target for its first manned mission to the Red Planet.

In order to make such a feat even feasible, scientists need to find ways to counter some of the effects that long-term exposure to weightlessness is known to have on astronauts, such as the upwards redistribution of fluid around the body.

The phenomenon has a number of negative effects, ranging from a puffy face to the heart having to pump a higher volume of liquid to increased pressure on the eyeball which can cause problems with vision and, in extremis, blindness. One study has found that nearly two-thirds of astronauts on long missions suffer some form of visual impairment as a result of being in space.

Kelly and Kornienko, whose colleagues on the ISS included British astronaut Tim Peake, tested special Russian equipment designed to return fluid to the lower limbs as well as special exercise regimes designed to counter the wastage of bone and muscle caused by the lightened physical load of zero gravity.

The result is an often difficult transition for astronauts once they return to terra firma as they learn to recalibrate every part of their body, including lips and tongue, to the pull of gravity.

Aside from the effects of sleep loss, increased risk of kidney problems and a 20 per cent dip in aerobic capacity, some of the harshest problems faced by astronauts are psychological.

Speaking before he landed, Kelly said: “Physically I feel pretty good but the hardest part is being isolated in the physical sense from people on the ground who are important to you. There’s a loss of connection.”

Scientists are concerned that extending such a disconnection over a period of double the longest previous space journey and a distance of some 48 million miles may create difficulties every bit as tricky to overcome as the physical problems of flying to Mars.

Not that the physical effects of space on the human body are undaunting.

One of the experiments conducted on Kelly is to measure the effects of space radiation on small sections of DNA called telomeres, which help regulate the body’s rate of ageing and its susceptibility to diseases such as cancer.

Scientists believe that as well travelling at 17,000mph in orbit, astronauts may be therefore also ageing faster than their earthbound brethren.

NASA nonetheless last night remained resolutely upbeat about the usefulness of its study. Charles Bolden, the head of the agency, said: “Scott has become the first American astronaut to spend a year in space, and in so doing helped us take one giant leap toward putting boots on Mars.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments