Ancient ‘monster penguin’ is largest ever discovered and weighed as much as a gorilla

Ancient penguins ‘would have been an utterly astonishing sight on the beaches of New Zealand’, says researcher

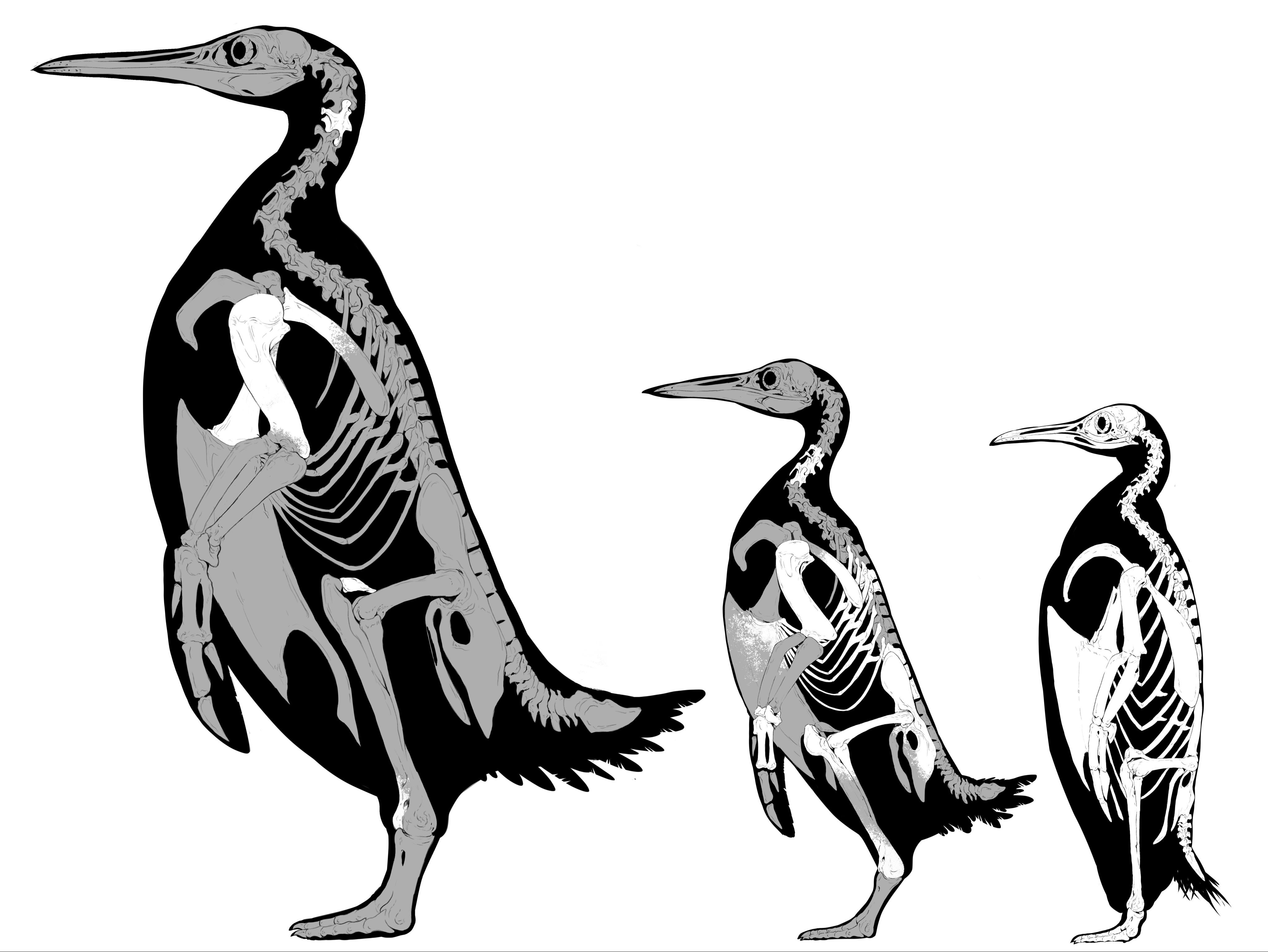

Scientists have discovered a new “monster” penguin species, which lived 57 million years ago and was three times the size of its predecessors alive today.

Weighing nearly 160kg, the same as an adult gorilla, the fossilised bones of Kumimanu fordycei was discovered in 57 million-year-old beach boulders in North Otago, on New Zealand’s South Island in 2017.

Kumimanu is an existing genus, which means “monster bird”, while the second part of the name honours Dr Ewan Fordyce, who is said to have been instrumental in building New Zealand’s paleontology programme.

The penguin is thought to have lived roughly five to 10 million years after the end-Cretaceous extinction which wiped out non-avian dinosaurs.

“Fossils provide us with evidence of the history of life, and sometimes that evidence is truly surprising,” said co-author Dr Daniel Field, from the University of Cambridge. “Many early fossil penguins attained enormous sizes, easily dwarfing the largest penguins alive today.

“Our new species, Kumimanu fordycei, is the largest fossil penguin ever discovered—at approximately 350 pounds, it would have weighed more than [basketball player] Shaquille O'Neal at the peak of his dominance.”

Once the bones were exposed from the boulders, the team used laser scanners to create digital models of them and compare them to other fossil species, modern penguins, and flying diving birds like auks.

To estimate the size of the new species, the team measured hundreds of modern penguin bones and calculated a regression using flipper bone dimensions to predict weight.

They concluded that the largest flipper bones belong to a penguin that tipped the scales at 154 kg – multiple times heavier than a modern-day emperor penguins, which typically weigh between 22 and 45kg and are the tallest and heaviest of all living penguins.

Penguins have the richest fossil record of any bird because their strong, dense bones were more likely to be preserved than the fragile skeletons of other species, according to Dr Field.

Multiple specimens of a second, albeit smaller, penguin species were also found, weighing 50kg and named Petradyptes stonehousei – in honour of the late Dr Bernard Stonehouse (1926-2014), the first person to observe the full breeding cycle of the emperor penguin, a major milestone in penguin biology.

While penguins were previously much larger than they are today, Dr Field told The Times that he suspects they later shrank in size as large mammals, including the precursors to whales, moved into the seas and began to compete with them for food.

Writing about their find in the Journal of Paleontology, Daniel Ksepka, a curator at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, said the bird’s massive size may have given it a competitive edge, which enabled it to beat rivals for food and territory, and maintain its body heat underwater.

“Size conveys many advantages,” said Dr Ksepa. “A bigger penguin could capture larger prey, and more importantly it would have been better at conserving body temperature in cold waters.

“It is possible breaking the 100lb size barrier allowed the earliest penguins to spread from New Zealand to other parts of the world.”

Co-author Dr Daniel Thomas, from Auckland’s Massey University, questioned whether Kumimanu fordycei “had an ecology that penguins today don’t have, by being able to reach deeper waters and find food that isn’t accessible to living penguins”.

Dr Field said he hoped that future fossil discoveries would shed more light on the early penguin’s biology.

“Kumimanu fordycei would have been an utterly astonishing sight on the beaches of New Zealand 57 million years ago, and the combination of its sheer size and the incomplete nature of its fossil remains makes it one of the most intriguing fossil birds ever found,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments