Mission to the sun will protect us from devastating solar storms and help us travel deeper into space

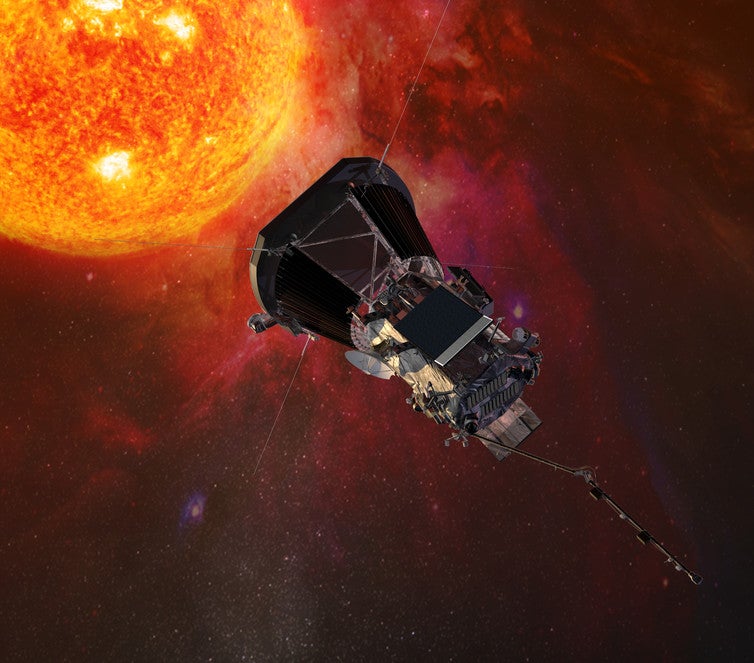

The Parker probe will go closer to the sun than any other spacecraft has dared go before – literally touching it

From prayer and sacrifice to sunbathing, humans have worshipped the sun since time immemorial. And it’s no wonder. At around 150m km away, it is close enough to provide the light, heat and energy to sustain the entire human race.

But despite the fact that our parent star has been studied extensively with modern telescopes – both from home and in space – there’s a lot we don’t know about it.

This is why NASA has recently announced plans to launch a revolutionary probe, set to lift-off in 2018, that will literally touch it.

Initially dubbed the Solar Probe Plus mission, the spacecraft has now been renamed the Parker Solar Probe. This is to honour physicist Eugene Parker who carried out important work on the solar wind – a stream of charged particles from the sun.

There have been many missions to investigate the sun. In 1976, the Helios 2 spacecraft came as close as 43m km from the sun’s atmosphere.

But the $1.5 billion Parker probe will travel to just 6m km above the solar surface – some nine times closer than any spacecraft has ever gone before. This will open a new era of understanding as, for the first time, sensors will be able to detect and analyse phenomena as they occur in the sun.

While the cruising altitude of the mission may sound like a safe distance at millions of kilometres, the sun’s immense energy will relentlessly bombard the payload with heat. An 11.5cm thick carbon composite shroud, similar to what modern Formula 1 race cars employ in their high-performance braking systems, will shield the sensitive equipment. This will be crucial as temperatures will soar beyond 1,400°C.

At these extreme temperatures, the solar arrays that power the spacecraft will retract. This manoeuvre will allow the instruments and power sources to remain close to room temperature in the shadow of the carbon composite shield. Just as well, as the spacecraft will experience radiation 475 times more intense than Earth orbit.

Any errors in the planned spacecraft trajectories could result in the probe sinking deeper into the sun’s atmosphere, which is several million degrees hot. This could ultimately destroy the spacecraft.

Solar science

So what can we learn from this risky mission? The dynamic activity brought about by supercharged particles and radiation being released from the sun – encountering the Earth as they pass through the inner solar system – is called space weather. The consequences of space weather can be catastrophic, including the loss of satellite communications, changes to the orbits of spacecraft around Earth and damaging surges throughout global power grids. Most important is the risk to astronauts exposed to the powerful ionising radiation.

The devastating cost of such fierce electromagnetic storms has been estimated at $2 trillion, resulting in space weather being formally listed in the UK’s National Risk Registry.

The new solar probe will revolutionise our understanding of what conditions are necessary in the sun’s atmosphere to generate severe bouts of space weather by making direct measurements of the magnetic fields, plasma densities and atmosphere temperatures for the first time. In a similar way to how an elastic band can snap following excessive stretching, it is believed that the continual twisting and churning of the magnetic field lines that permeate the solar atmosphere may give rise to particle acceleration and radiation bombardment. Once the magnetic fields break, we can experience severe space weather.

Unfortunately, we presently have no direct method of sampling the sun’s magnetic fields. Scientists are attempting to uncover new techniques that will allow the twists, strengths and directions of the sun’s powerful fields to be determined, but so far they can’t provide an accurate enough understanding. This is where the Parker probe will provide a new age of understanding, since it will be able to sample the sun’s powerful magnetic fields while there.

Round-the-clock observations and direct measurements of the atmospheric conditions responsible for increased levels of space weather are paramount in order to provide crucial warning of imminent solar threats. An instrument suite on-board the probe, the FIELDS suite, will provide such unprecedented information. Scientists can then feed this into intensive computer models, ultimately allowing space, aviation, power and telecommunication authorities to be alerted when potentially devastating space weather is imminent.

Of course, understanding the origins of space weather also has implications for other important areas of astrophysical research. It will allow space agencies to better protect astronauts during future manned missions to Mars, where the thinner Martian atmosphere offers little protection to incoming solar radiation.

Also, by being able to accurately model the effects of the streaming solar wind, future spacecraft will be able to effectively use solar sails to help them reach further into the depths of the solar system, perhaps eventually opening up the possibility of truly interstellar travel.

David Jess is a lecturer and STFC Ernest Rutherford fellow at Queen's University Belfast. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.conversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments