Maria Reiche: Who was the German governess who devoted her life to Peru's mysterious Nazca Lines?

'Lady of the Lines' theorised strange drawings of birds and animals carved into desert plains were part of ancient astronomical calendar and was crucial to securing their preservation

German mathematician Maria Reiche (1903-98), known for her pioneering work into Peru's ancient Nazca Lines, was born in Dresden 115 years ago today.

Honoured in today's Google Doodle, Reiche became obsessed with solving one of Latin America's greatest mysteries: why did the land's ancient people carve giant bird and animal geoglyphs into the desert plains?

She had first arrived in Peru in 1932 after completing her studies, having accepted a job as governess to the children of the German consul in Cuzco.

She quickly became enraptured by the country - despite losing a finger to gangrene after being pricked by a cactus - visiting the Andes and the high plains of southern Peru before relocating to Lima in 1934.

Here she worked as teacher of German and befriended American ex-pat Amy Meredith, who would become her partner and who ran a fashionable local coffee shop where she first encountered New York academic Paul Kosok.

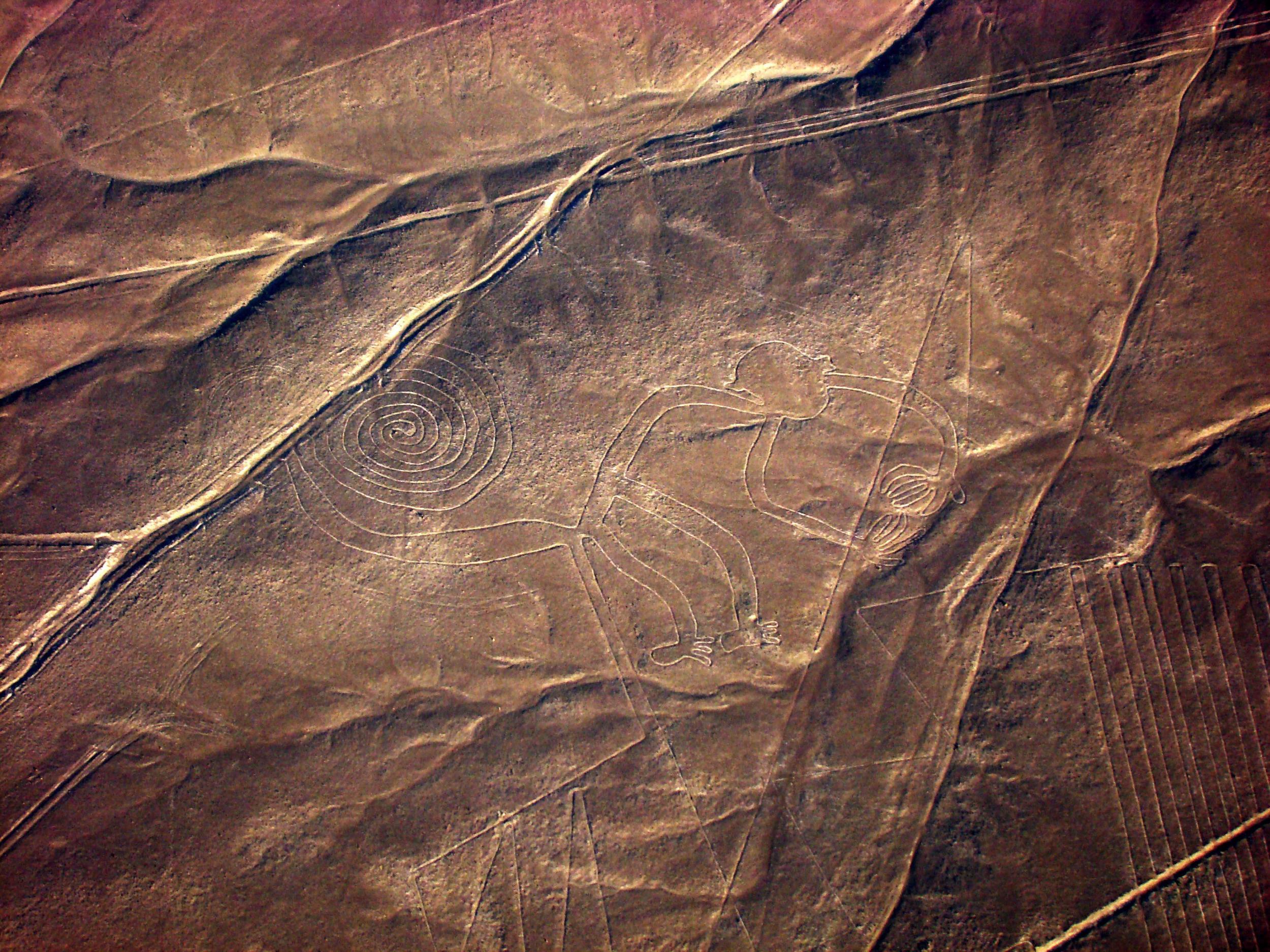

It was Kosok who introduced her to the strange line drawings of creatures in the sands of Nazca, 248 miles from the capital. First discovered by Peruvian archaeologist Toribio Mejia Xesspe a decade earlier, Kosok had photographed them from the air and realised their true form.

Reiche was transfixed by his account and, after visiting the 140 square mile site, committed herself to their study as Kosok's side, describing the landscape as "a huge blackboard where giant hands have drawn clear and precise geometric designs".

Spending many nights camping in the desert, Maria became an object of curiosity herself: "The locals either thought I was a spy or completely mad. Once a drunk threatened me with a stone, so I took out my sextant and pointed it at him. He ran off screaming, and the next day the local papers ran the story of a mad and armed German spy in their midst."

Reiche and Kosok's study of the Nazca Lines in the 1940s led to the dramatic conclusion that the beasts were actually roughly equivalent to the signs of the zodiac and that they together comprised an early astronomical calendar, mapping out the celestial bodies in the heavens.

Her book The Mystery of the Pampas (1949) detailed the theory that the giant monkey geoglyph was the Nazca interpretation of the Great Bear constellation, whose movement across the night sky was used to mark time and predict the onset of the rainy season. Her work debunked a myth popularised by Swiss conspiracy theorist Erich von Daniken that they were made by extraterrestrials.

Although Reiche's conclusion has now been largely sidelined in favour of the idea that the geoglyphs served a more earth-bound ceremonial purpose, she nevertheless played a vital role in preserving them, sweeping the lines, preventing vehicles from driving over them and ensuring they received Unesco protected status in 1994.

"The Lady of the Lines" spent her days living in a Nazca tourist hotel, was granted Peruvian citizenship in 1992 and published her complete scientific findings Contributions to Geometry and Astronomy in Ancient Peru in 1993 at the age of 90. She died of ovarian cancer in June 1998, a beloved figure in her adopted homeland.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments