LSD makes the brain more ‘complete’, scientists say as they claim to have unlocked secrets of hallucinogenic drugs

By breaking down parts of the brain that are usually separate, drugs like LSD return us to a childlike state — and that effect on well-being could last long after the drugs’ effects have worn off

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.LSD makes the brain more “complete”, scientists have claimed in a pioneering and controversial new study.

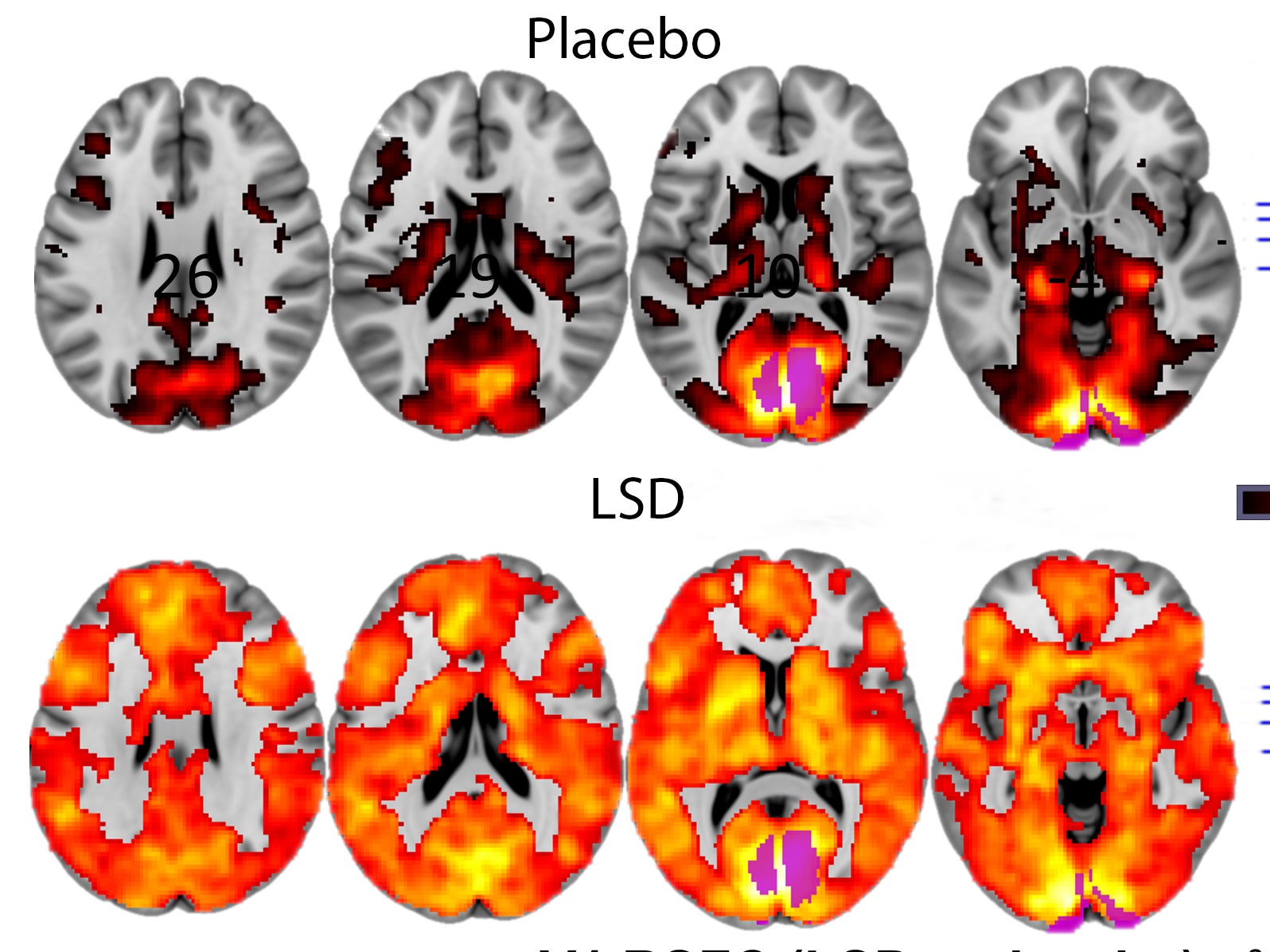

The drug breaks down the parts of the brain that usually separate different functions, like vision and movement, creating a more “integrated or unified brain”, the researchers claim. They also found that people who are having drug-induced hallucinations “see” with various other parts of their brain, not just the visual cortex that is active in normal vision.

Those effects might account for the religious feelings that people often report after having taken the drug, the researchers say — a claim that if true could answer some of the deepest questions of drug culture. And those same effects on a person’s well-being might carry on long after the effects of the drug has worn off.

"Normally our brain consists of independent networks that perform separate specialised functions, such as vision, movement and hearing - as well as more complex things like attention,” said Robin Carhart-Harris, who led the research and is the first scientist in 40 years to test LSD on humans, in a statement. “However, under LSD the separateness of these networks breaks down and instead you see a more integrated or unified brain.

"Our results suggest that this effect underlies the profound altered state of consciousness that people often describe during an LSD experience. It is also related to what people sometimes call 'ego-dissolution', which means the normal sense of self is broken down and replaced by a sense of reconnection with themselves, others and the natural world.

“This experience is sometimes framed in a religious or spiritual way - and seems to be associated with improvements in well-being after the drug's effects have subsided."

By breaking down the constraints that usually keep parts of the brain separate, psychedelic drugs return their users back to a state that is more like childhood, the researchers said in work published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Our brains become more constrained and compartmentalised as we develop from infancy into adulthood, and we may become more focused and rigid in our thinking as we mature,” said Dr Carhart-Harris. “In many ways, the brain in the LSD state resembles the state our brains were in when we were infants: free and unconstrained.

“This also makes sense when we consider the hyper-emotional and imaginative nature of an infant's mind."

"We are finally unveiling the brain mechanisms underlying the potential of LSD, not only to heal, but also to deepen our understanding of consciousness itself."

And those effects could be even further encouraged with the use of music, according to results from the same study, which was published in the journal European Neuropsychopharmacology. Listening to music while under the influence of the drug led the visual cortex to receive information from the part of the brain that usually deals with mental images and memory — and the more it did so, the more people reported seeing complex visions including those from earlier in their lives.

Those discoveries help answer questions that have been asked for decades about how exactly LSD works, and what it does to the brain, the researchers said.

Former Government drugs adviser Professor David Nutt, director of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College, one of the project's senior researchers, said: "Scientists have waited 50 years for this moment - the revealing of how LSD alters our brain biology.

"For the first time we can really see what's happening in the brain during the psychedelic state, and can better understand why LSD had such a profound impact on self-awareness in users and on music and art. This could have great implications for psychiatry, and helping patients overcome conditions such as depression," he said.

Professor Nutt was removed from his job as the chair of the Government’s drug advisory council in 2009, after he said that drugs including ecstasy and LSD were less harmful than alcohol and tobacco.

The new findings could prove similarly controversial, with some involved in the study suggesting that they could show how LSD could be used for healing and for finding new forms of knowledge. Eventually they might be used to treat psychiatric disorders and allow researchers to treat conditions such as depression and addiction, which tend to arise from entrenched thought patterns.

"We are finally unveiling the brain mechanisms underlying the potential of LSD, not only to heal, but also to deepen our understanding of consciousness itself,” said Amanda Feilding, director of the Beckley Foundation, a charity that promotes evidence-based drugs policy and worked with the researchers on the study.

The research looked at 20 volunteers, all of whom received both LSD and placebo and were deemed psychologically and physically healthy. Each of them had taken some kind of psychedelic drug before taking part in the study.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments