3D-printed ‘living ink’ developed to aid organ transplants and clean up pollution

Adding live bacteria to materials has ‘enormous potential’ in medical and environmental applications

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ink containing bacteria has allowed scientists to create “living materials” with a range of potential applications from skin grafts to cleaning up chemical spills, according to a new study.

The technology underpinning 3D printing has progressed rapidly in recent years, but it has focused on more conventional materials such as plastic and metal.

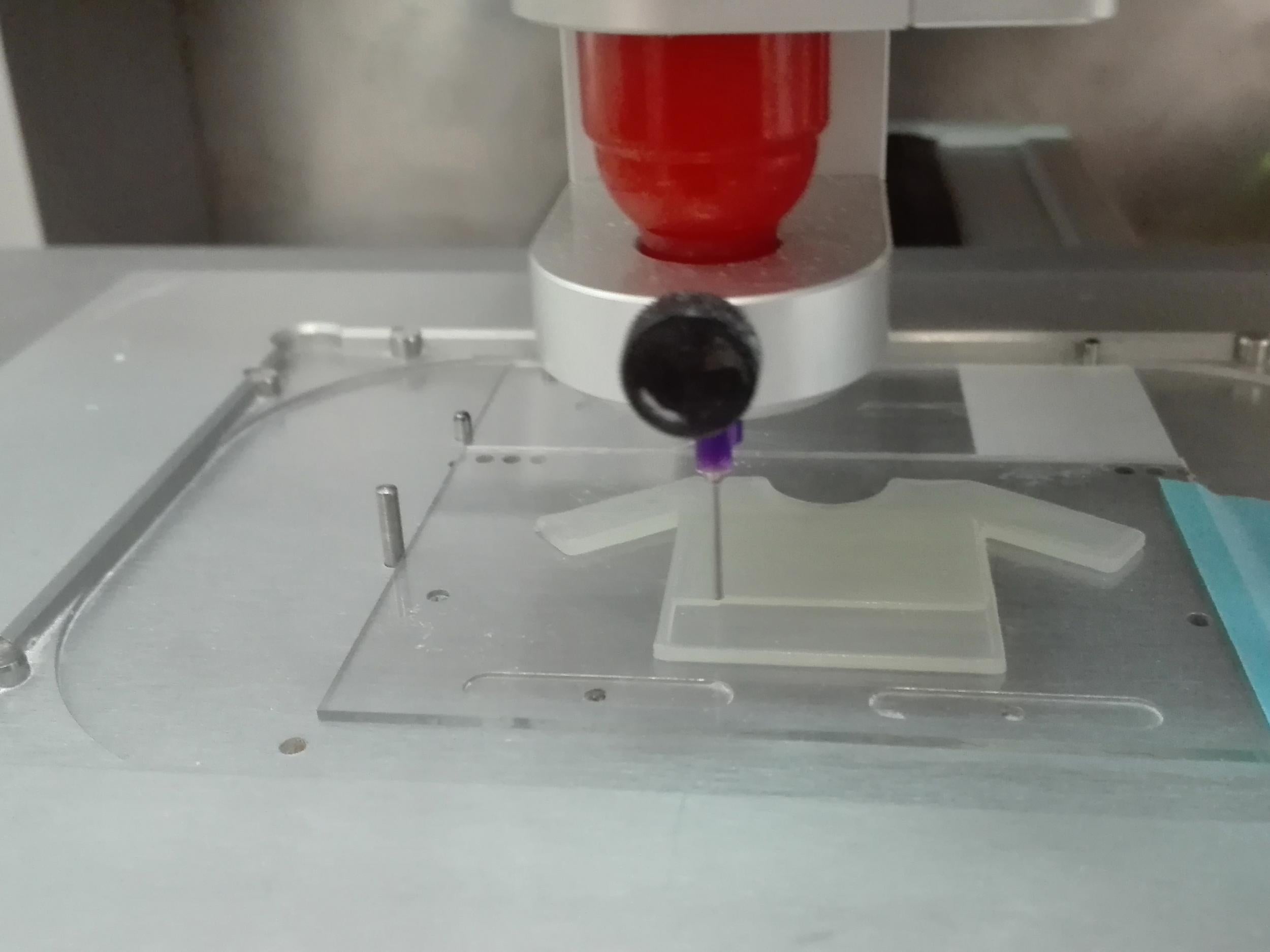

By simply embedding bacteria into a 3D printing ink, a team of scientists has created a “functional living ink", or “Flink”.

Flink could have a variety of uses, from breaking down chemical pollutants to creating skin grafts.

Bacteria possess a huge range of abilities, meaning the functions of materials produced using Flink are as varied as the bacteria researchers decide to incorporate into it.

"Printing using bacteria-containing hydrogels has enormous potential, as there is such a wide range of useful bacteria out there," said Dr Patrick Rühs, a researcher at ETH Zürich university, who co-authored the study.

Though people generally associate bacteria with diseases, the strains used by Dr Rühs and his colleagues in their Science Advances study are harmless.

The scientists printed using two species of bacteria, including one that produces a natural compound called cellulose.

Cellulose can be used to make supportive scaffolds for skin transplants, or to aid in the transplantation of organs.

The researchers printed a film of Flink onto the uneven surface of a doll’s face, to demonstrate how their new ink could be used to make personalised cellulose scaffolds.

The other species of bacteria Dr Rühs and his collaborators included in their Flink was one that breaks down the toxic pollutant phenol.

Besides degrading such toxins, potential environmental applications for Flink include the creation of sensors that detect toxins in drinking water, or filters to deal with oil spills.

More work needs to done to explore all of these functions, but the scientists are confident that bacteria could make a valuable addition to many materials. "As bacteria require very little in the way of resources, we assume they can survive in printed structures for a very long time," said Dr Rühs.

The researchers hope that future work on Flink will reveal a world of possibilities not offered by non-living inks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments