The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Jurassic fossil of huge egg-laying fanged rat discovered in Arizona, offering insight into evolution of reptiles into mammals

Discovery of trilodont with 38 hatched and unhatched offspring indicates critical step in the evolution of mammals was trading big litters for big brains, study says

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

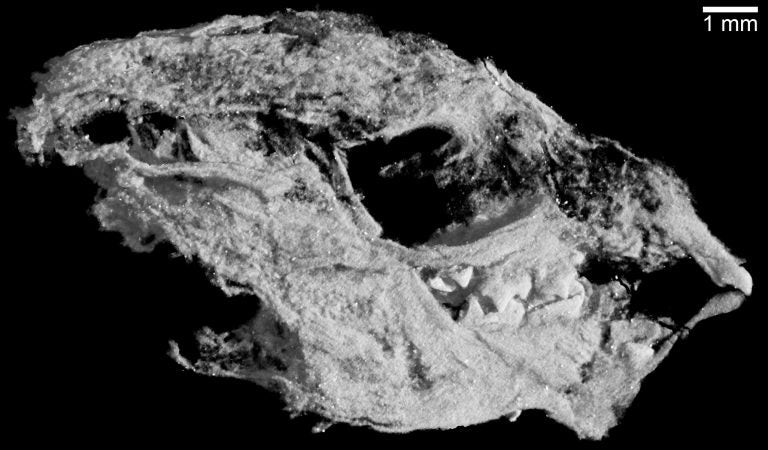

Your support makes all the difference.A “rarest of the rare” fossil of an enormous fanged rat-like animal surrounded by a litter of 38 hatched and unhatched offspring has been unearthed in Arizona, offering new insight into the transition between reptiles and mammals during the Jurassic period.

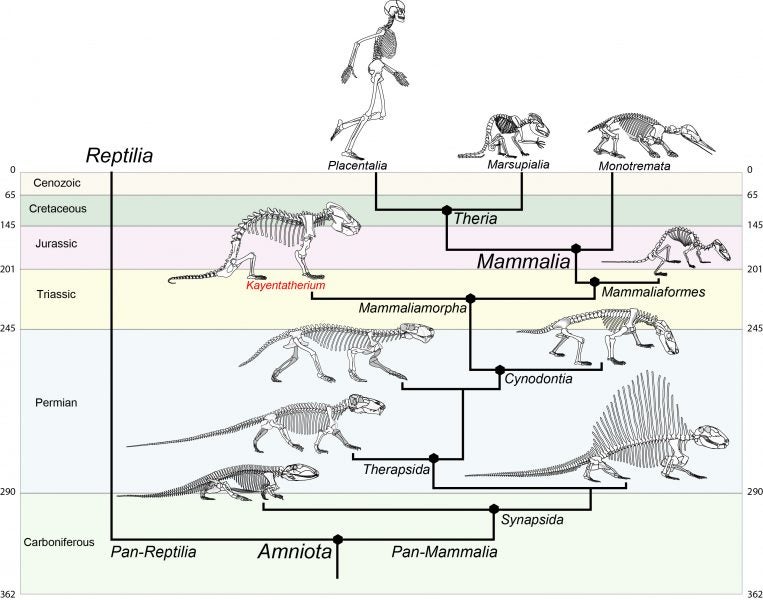

Mammals are today distinguished by their means of reproduction in which they produce relatively few, live young. In comparison, reptiles lay large clutches of eggs.

But this find, reported in the journal Nature, shows the species, which is very close to modern mammal species, still had a primitive form of reproduction, and laid eggs in the same numbers as reptiles.

The creature, named Kayentatherium wellesi, and which was a forerunner to modern mammals and belonged to a group known as the tritylodonts, was about the size of a small dog, and had large fangs on both its upper and lower jaw.

Despite its appearance, it was herbivorous, and would have lived alongside dinosaurs about 185 million years ago.

The remarkable discovery of the animal’s offspring comes a full 18 years after the initial mother’s remains were found, when palaeontologists re-examined the sediment sample and carried out CT scans to reveal the huge litter.

“Looking at the CT scans I was able to discover baby after baby after baby,” said study leader Eva Hoffman, who led the research as a graduate student in geosciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

“These babies are from a really important point in the evolutionary tree,” she added. “They had a lot of features similar to modern mammals, features that are relevant in understanding mammalian evolution.”

Zhe-Xi Luo, a palaeontologist and professor at The University of Chicago, described the discovery as “stunning” and said they would provide scientists valuable insight into mammal evolution.

“These great fossils really gave us a rare glimpse of how early mammals evolved from their ancestors,” he said.

The highly detailed scans allowed Ms Hoffman to examine the shape of the offsprings’ skulls, which appear as “scaled down replicas” a tenth of the size of the adult and with all features in proportion - a trait typically seen in reptile offspring. In modern mammals, young are born with shortened faces and bulbous heads to account for big brains.

The discovery that Kayentatherium had a tiny brain and many babies, despite otherwise having much in common with mammals, suggests a critical step in the evolution of mammals was trading big litters for big brains, and that this step happened later in mammalian evolution, the study said.

Ms Hoffman co-authored the study with her graduate adviser, Jackson School Professor Timothy Rowe, who unearthed the fossil in 2000.

Sebastian Egberts, a former graduate student and fossil preparator at the Jackson School, spotted the first sign of the babies years later when a grain-sized speck of tooth enamel caught his eye in 2009 as he was unpacking the fossil.

“It didn’t look like a pointy fish tooth or a small tooth from a primitive reptile,” said Mr Egberts, who is now an instructor of anatomy at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine.

“It looked more like a molariform tooth (molar-like tooth) — and that got me very excited.”

A CT scan of the fossil undertaken in 2009 revealed a handful of bones inside the rock. But it took advances in CT-imaging technology during the next seven years, the expertise of technicians at UT Austin’s High-Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography Facility (UTCT), and extensive digital processing by Ms Hoffman to reveal the rest of the offspring - not just their jaws and teeth, but complete skulls and partial skeletons - the University of Texas said in a statement.

“There are additional deep stories on the evolution of development, and the evolution of mammalian intelligence and behaviour and physiology that can be squeezed out of a remarkable fossil like this now that we have the technology to study it,” Professor Rowe said.

To find so many offspring together from the Jurassic period is unprecedented as young animals would tend to have been destroyed or eaten in the event they had not made it to adulthood.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments