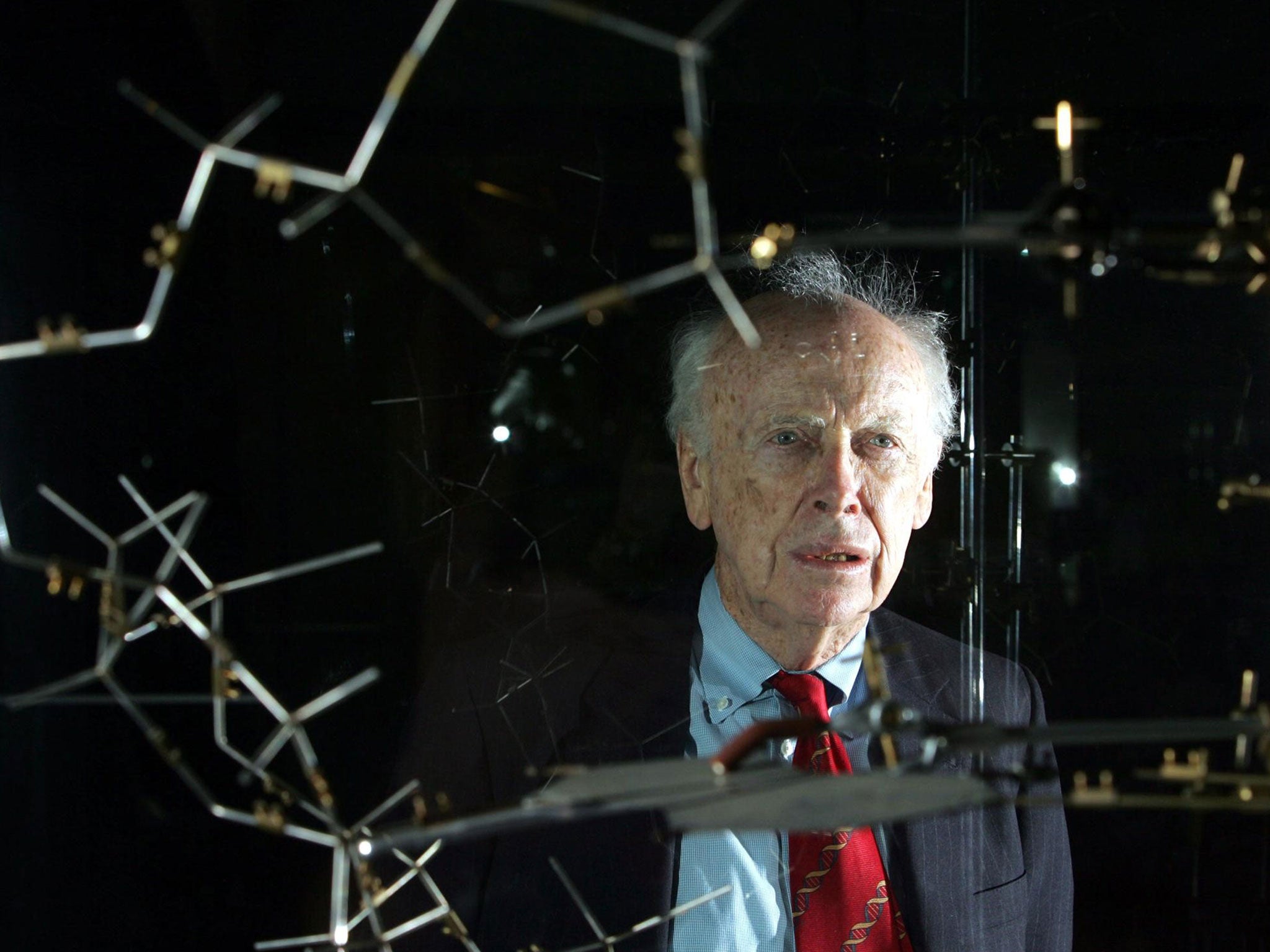

James Watson profile: A human riddle wrapped in a DNA double helix

The Nobel medal has gone, sold for $4.75m. So has his reputation, besmirched by allegations of racism. So is James Watson the victim of political correctness – or a loose cannon with unsavoury opinions he can’t keep to himself?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Where does one begin with Dr James Dewey Watson, the brilliant co-discoverer of the DNA double helix, best-selling author, Nobel laureate, iconoclast and scientific racist?

This week, Watson’s 23-carat gold Nobel medal went under the hammer at Christie’s in New York, sold by telephone auction for $4.75m (£3m) to an anonymous buyer. It had been with him since 1962 but will now help to pay for the impoverished retirement of the 86-year-old godfather of molecular biology. Or so he would have us believe.

In an interview with the Financial Times last week, Watson claimed that he has been shunned by the scientific community for daring to suggest that race and intelligence are linked. He had become an “unperson”, he said, for comments attributed to him in a newspaper interview published in 2007.

“Because I was an ‘unperson’ I was fired from the boards of companies, so I have no income, apart from my academic income,” he said, before adding rather mischievously that he needs the money not to pay his gas bill, but to buy a David Hockney painting, and to make some charitable donations.

Watson said that he was “not a racist in a conventional way” and apologised once again for remarks attributed to him seven years ago by a Sunday Times journalist, who also happened to be a former hand-picked student of his at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, where he was the director for nearly half a century.

That long, 4,000-word article published in the magazine section was largely about fairly uncontroversial matters relating to a new biographical book by Watson. But towards the end, the journalist, Charlotte Hunt-Grubbe, included a few disjointed quotes from Watson that effectively ended his career and his standing among many of his peers.

“He says that he is ‘inherently gloomy about the prospects of Africa’ because ‘all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – whereas all the testing says not really’,” Hunt-Grubbe wrote.

“His hope is that everyone is equal, but he counters that ‘people who have to deal with black employees find this not true’. He says that you should not discriminate on the basis of colour, because ‘there are many people of colour who are very talented, but don’t promote them when they haven’t succeeded at the lowest level',” she wrote.

Other newspapers, led by The Independent, took up the story which broke just as Watson had landed at Heathrow to conduct a publicity tour of Britain for his book, appropriately entitled Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science.

In the work, he expanded on this theme of racial differences in intelligence, writing that “there is no firm reason to anticipate that the intellectual capacities of peoples geographically separated by their evolution should prove to have evolved identically. Our wanting to reserve equal powers of reason as some universal heritage of humanity will not be enough to make it so.”

Understandably, politicians ranging from Keith Vaz, the Labour chair of the Home Affairs Select Committee, to Ken Livingstone, the then Mayor of London, were incensed that Watson was about to be feted at meetings up and down the country, from London to Edinburgh. “It is sad to see a scientist of such achievement making such baseless, unscientific and extremely offensive comments,” Mr Vaz said.

The Science Museum in London, where Watson was due to deliver a sold-out lecture, cancelled the gig, saying that the Nobel laureate had “gone beyond the point of acceptable debate”. Edinburgh University swiftly followed and Watson and his publishers were suddenly looking at a car wreck of a promotional book tour.

But worse was to follow. His beloved Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory, where he was Chancellor, suspended him from his administrative duties and recalled him to New York in an attempt to protect itself from the inflammatory implication that it was somehow involved in promoting eugenics and the idea of there being a genetic basis to race and intelligence.

On the eve of his departure, I met Watson at a sparsely attended book reception at the Royal Society and asked him whether he had really said what was attributed to him. “I cannot understand how I could have said what I am quoted as having said,” he replied.

He then suggested that the comments may even had been misheard or misunderstood after the interview with Hunt-Grubbe when he was driving her back to the airport, as was his custom with visiting journalists, entertaining them with gossipy conversation.

He also rather bitterly pointed out that Hunt-Grubbe, whom he had specifically requested to interview him to promote his book, had failed to turn up for his Royal Society reception. “It speaks volumes,” he whispered conspiratorially, as if to suggest that Hunt-Grubbe must harbour some regrets.

But for all his expressed astonishment about the quotes attributed to him, it is difficult not to believe that he said what he was quoted as saying, although the context may well have been different and more nuanced than implied by the article.

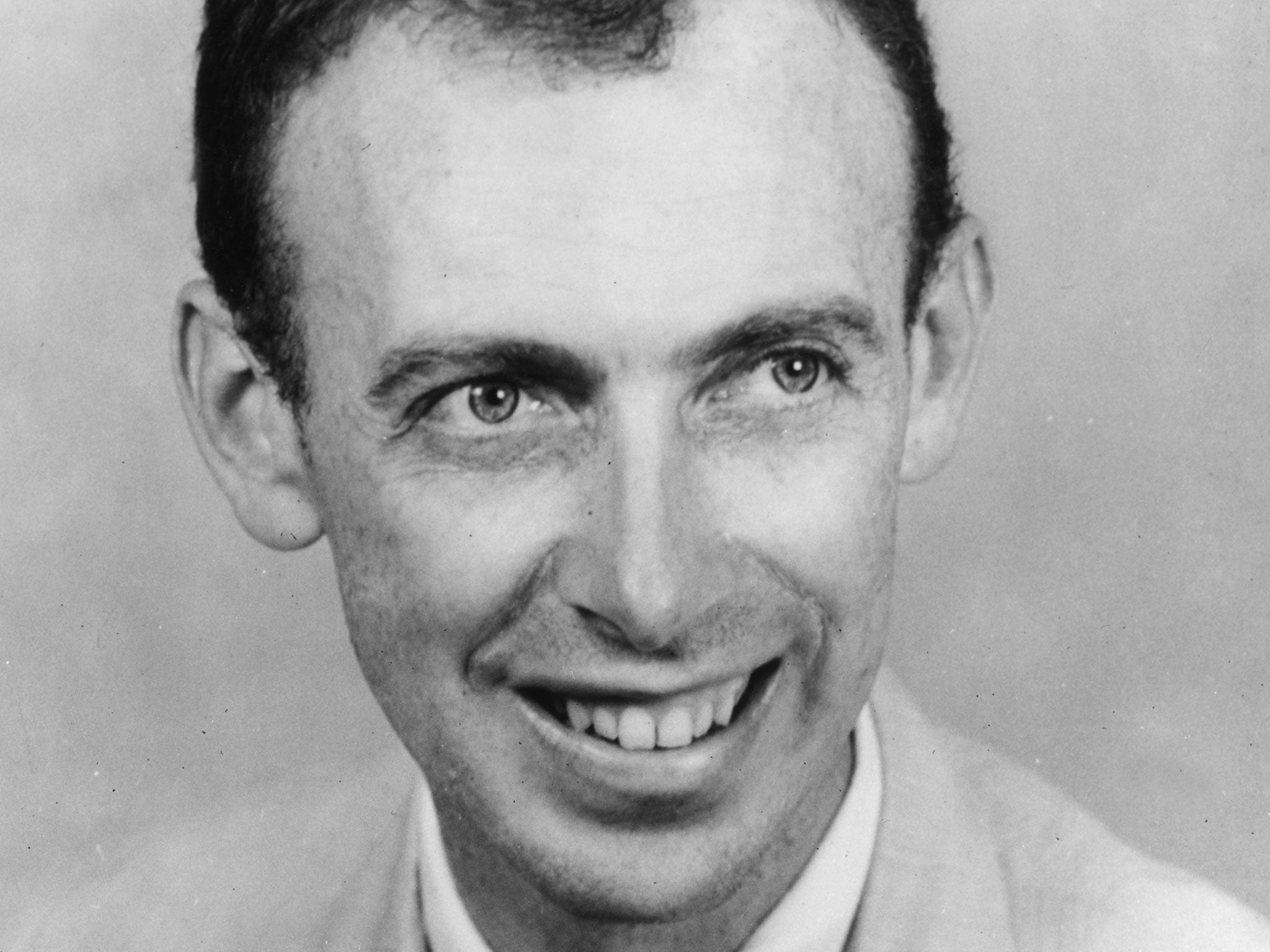

Anyone who has followed Watson over the years since he carried out his Nobel-Prize-winning work at the age of 25, knows about his capacity to offend. Whether written or spoken, his words have frequently over the years caused controversy and outrage.

He wrote the inside story of his co-discovery in a racy little book called The Double Helix, published in 1968. It became an immediate bestseller, but shocked other scientists including Francis Crick, his collaborator at Cambridge University, who thought it was low-brow tittle-tattle.

Watson particularly incensed feminists with his sexist descriptions of Rosalind Franklin, who with Maurice Wilkins had produced the X-ray images at King’s College London on which Crick and Watson had built their model of the DNA helix. Franklin, or “Rosy” as Watson insisted on calling her in his book, was “not unattractive, and might have been quite stunning had she taken even a mild interest in clothes”.

It could be argued that this was a different age to now, but then again these words come from a man who also joked “the best place for a feminist is in another person’s lab”.

I know from personal experience that his humour can stretch the boundaries of acceptability. When I interviewed him at Cold Harbour in 2003, I asked him about germ-line gene therapy, the idea of modifying the genes of future generations which I knew he was in favour of considering as a viable medical technique.

“I always draw a laugh when I say that everyone knows the Irish need improvement,” he said deadpan but with a twinkle in his eye. As someone with obvious Irish ancestry, I could have taken offence, but I also knew that he has about as much Irish DNA as me and laughed it off.

But there have been other outrageous comments that cannot be laughed away, such as his view that dark-skinned people may have a bigger libido or the idea that women should be able to abort foetuses with “gay genes”, which he later said was misunderstood as he was talking about being pro-choice rather than being anti-homosexual.

But this capacity to go dangerously and excitingly off-piste is why journalists like to interview him so much. We know, and he knows long before you know it, that the interview will never be boring.

As long ago as 1990, the journal Science published an editorial stating: “To many in the scientific community, Watson has long been something of a wild man, and his colleagues tend to hold their collective breath whenever he veers from the script.”

The evolutionary biologist Edward O Wilson, who had clashed with Watson in the 1960s when he became a Harvard professor at the age of 28, famously called him the “Caligula of biology” who was given a licence to say anything that came to mind because of the greatness of his discovery.

“Few dared to call him openly to account … for the compelling reason that the deciphering of the DNA molecule with Francis Crick towered over all that the rest of us had achieved and could ever hope to achieve,” Wilson once wrote.

Matt Ridley, a science writer, once said that Watson is always two or three steps ahead of you in a conversation, and for all his apparent foot-in-mouth gaffes, one can’t help but feel that it’s part of his plan to court controversy and thereby generate publicity.

It was surely no accident that he talked to the Financial Times a week before the Christie’s auction – what better media outlet to alert the world’s billionaires about an unmissible offer of a Nobel gold medal? Just as the Sunday Times interview with a friendly former student, who must have ticked all his boxes about “girls” being blond, pretty and posh, was a carefully planned publicity operation.

But what Watson failed to realise, perhaps, is that he long ago lost his licence to say publicly whatever comes to mind. He has learnt the hard way that there are other ways to avoid boring people.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments