The next IVF revolution: Older women more likely to have babies with new technique set to trial in UK this year

Thousands of women could benefit from controversial Augment technique if licence for pilot trial is granted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fertility doctors have applied for permission to use a controversial IVF procedure that promises to dramatically improve the chances of women older than 30 having babies by rejuvenating their eggs.

The technique effectively makes older eggs young again by adding a fresh set of “batteries” transferred from more youthful cells in the ovaries identified by a scientific process pioneered in the United States, scientists said.

A British fertility clinic has applied to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) for a licence to use the procedure in a pilot trial involving about 20 women undergoing IVF treatment. If the licence is granted, the trial is likely to begin later this year.

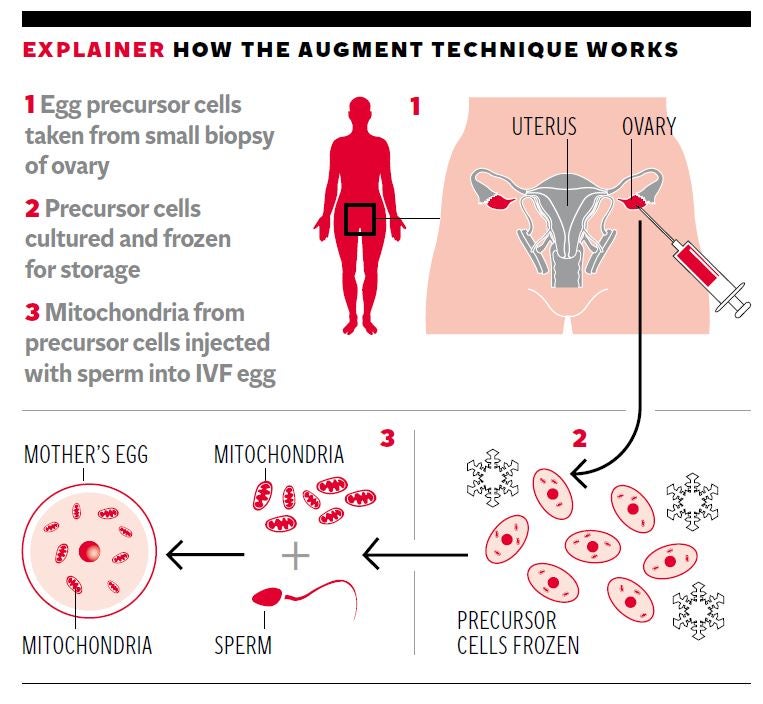

Thousands of women in their 30s and 40s, as well as younger women with fertility problems, could benefit from the technique which involves sucking out the mitochondria “power packs” from immature stem cells found in the ovary and injecting them into the mature egg cells or oocytes used in IVF.

IVF success rates fall dramatically with age. The chances of a successful IVF pregnancy are about 32 per cent for women under 35, about 21 per cent for women aged 38 to 39, five per cent for women aged 43 to 44 and less than two per cent for woman aged over 44.

The proponents of the technique argue that the failure of a fertilised egg to develop into a viable early embryo that can be transferred into the womb is often due to the decrepit nature of the egg’s ageing mitochondria – which can be remedied by adding fresher ones from so-called egg-precursor cells in the ovary.

However, some scientists have questioned whether there is enough scientific evidence to support even the existence of these egg-precursor stem cells. They will want the HFEA to carefully evaluate the proposal which could raise concerns over the health of any children born from the mitochondrial-transfer technique.

Nevertheless, Simon Fishel, professor of human reproduction and founder of Care Fertility in Nottingham, said there is evidence that injecting additional mitochondria into an IVF egg when it is fertilised with sperm improves the chances of the fertilised egg developing into a healthy early embryo.

“There is a body of scientific evidence suggesting that the mitochondria of eggs from some patients – those over 37, those previously shown to have poor-quality embryos after IVF – is part of the problem in getting viable embryos for such patients,” Professor Fishel told The Independent.

“Some scientific studies have shown that egg precursor cells can be harvested for their mitochondria, and if obtained they are healthy mitochondria, in contrast to the problematic eggs. Previous scientific studies have shown that donor mitochondria in such cases gives better quality and therefore more viable embryos with higher chances of pregnancy,” he said.

Care Fertility has applied for an HFEA licence using the egg-precursor and mitochondrial-transfer technology developed by OvaScience, a Boston-based company set up by fertility scientists in the United States. The technique, called Augment, is not however yet allowed in the US because it has been defined as a novel drug in need of extensive testing by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Professor Fishel said the fact that the Augment technique has not been allowed in the US should not influence whether it is given a licence in the UK “otherwise we are left with some big questions that will not advantage patients in the long run”.

If Augment works it could be as big a revolution in fertility treatment as ICSI, or intracytoplasmic sperm injection, where individual sperm cells are injected directly into unfertilised eggs with dramatic improvements in fertility rates, he said.

“It may provide new, revolutionary options for women to have their own genetic child. It’s a potential paradigm shift. But we have to get to the point where it does work to make it a more cost-effective solution,” Professor Fishel said.

Other experts were not convinced, however. Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, a specialist in mammalian reproduction at the Crick Institute in London and an HFEA adviser, said that the basic premise of the Augment approach is that there are “germline” stem cells within the ovary which can be used to supply fresh mitochondria.

“My view based on the science is that it’s difficult to believe. There is lots of evidence to suggest there are no germline stem cells remaining in the ovaries of mice, certainly from a week after birth. There is certainly no good evidence in any animal model that there are germline stem cells that actually give rise to oocytes,” Professor Lovell-Badge said.

“It all seems rather remarkable and a lot of people are sceptical. The HFEA may have a problem with that if there is not a robust scientific basis for the proposal. They [Ovascience] are charging at lot of money to do it and there is not much evidence that it does anything. They may have some information claiming to show that it does, but I’ve not seen this,” he said.

A representative of OvaScience was unavailable for comment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments