It's raining, it's pouring...molten iron: Scientists create first ever weather map of a 'brown dwarf'

Luhman 16B is the nearest brown dwarf to Earth, and the third nearest star system to our solar system

Scientists have created the first ever weather map of an unusual category of star known as a ‘brown dwarf’, unveiling in the process a new contender for the title of ‘worst weather in the universe’.

The surface of Luhman 16B is pelted with molten iron rain that falls from clouds made up of a gaseous form of the metal alongside other minerals. Temperatures are equally hellish, touching around 2,000F or 1,100C.

Scientists involved in the study described the planet as “extremely inclement".

At a distance of 6.5 light years from Earth, Luhman 16B is the nearest brown dwarf to our planet. These unusual objects are sometimes known as failed stars: they’re larger than gas giant planets such as Jupiter, but they’re still too small to achieve the cycle of nuclear fusion that defines a true star. The first brown dwarf was only confirmed by astronomers just 20 years ago.

"Previous observations have inferred that brown dwarfs have mottled surfaces, but now we can start to directly map them," said Ian Crossfield of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, lead author of one of the two new studies, in an official statement.

"What we see is presumably patchy cloud cover, somewhat like we see on Jupiter."

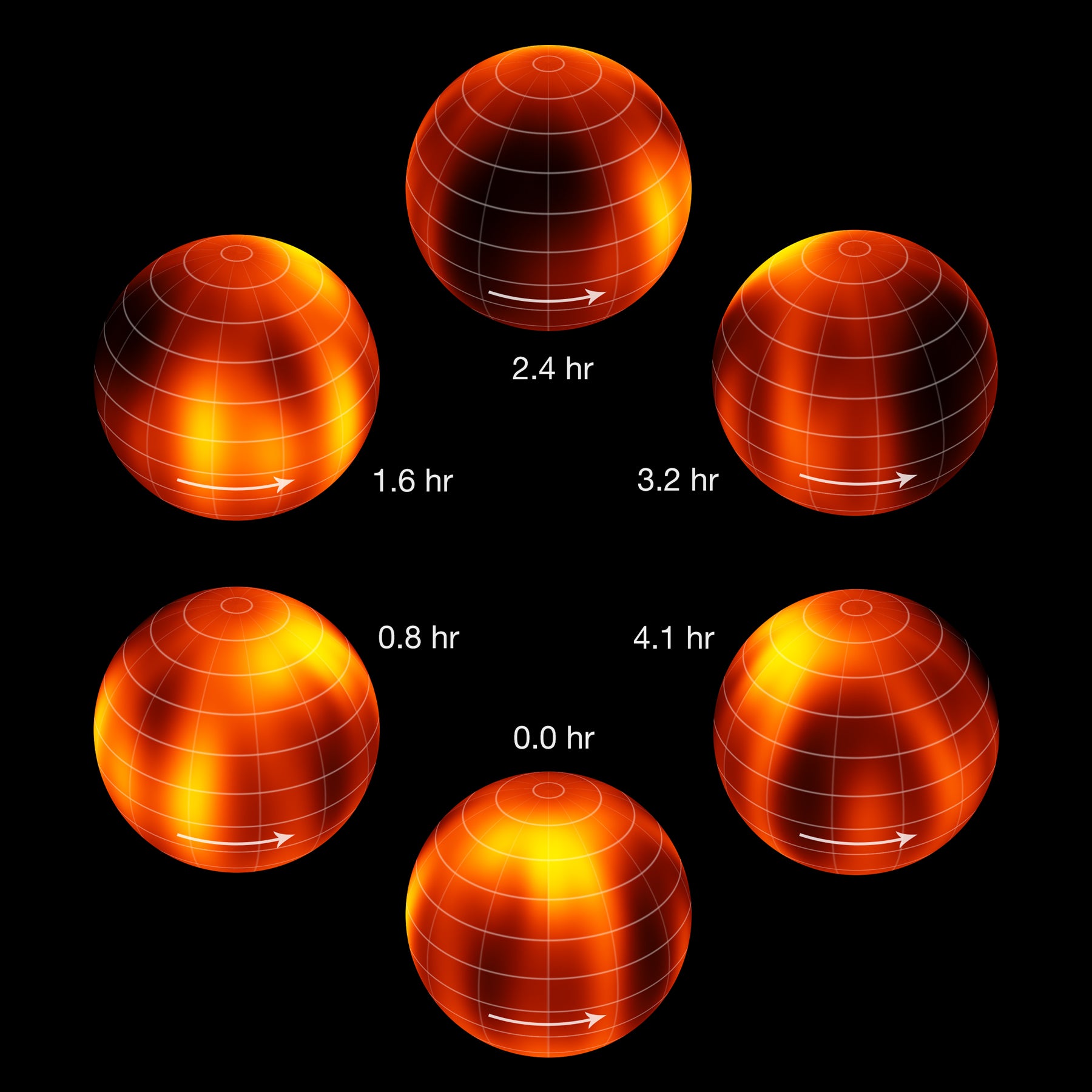

Crossfield and his team at the Max Planck institute used a technique known as Doppler imaging to create a weather map of Luhman 16B using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope.

"In the future, we will be able to watch cloud patterns form, evolve and dissipate — eventually, maybe exo-meteorologists will be able to predict whether a visitor to Luhman 16B can expect clear or cloudy skies," said Crossfield in a statement.

A second study headed by Beth Biller of the University of Edinburgh went to greater depths, examining brighter and darker clouds as the planet rotated (each rotation takes four hours) and using their observations to recreate what happens at different layers of the atmosphere.

“The exciting bit is that this is just the start,” said Biller. “With the next generations of telescopes, and in particular the 39 m European Extremely Large Telescope, we will likely see surface maps of more distant Brown Dwarfs – and eventually, a surface map for a young giant planet."

The results of the first study will appear in the journal Nature, whilst detailed atmospheric data will feature in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments