International Space Station: The experts' low-down on Tim Peake's high life

Congratulations Major, you'll be the first Brit on board. But where's the gym? What's for dinner? And do you really drink your own urine?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Greetings, spaceman! You've just docked with the greatest laboratory in the universe; you're doubtless exhausted after your journey up here from Kazakhstan, which peaked at 17,500mph (fast enough to fly from London to Edinburgh in 85 seconds). If you're lucky, it's taken you four brain-rattling hours. But there's a chance you've spent two days shoulder-to-shoulder in the Soyuz capsule with your new pals Yuri Malenchenko (of the Russian Federal Space Agency) and Tim Kopra (Nasa).

Soon you'll be stretching those legs as never before, but don't expect to “sit” back with a cool bag of recycled urine just yet. There's a lot to do. Sure, you know your stuff – you've trained for this for years – but we don't want you to miss a thing. So as you wait to enter the International Space Station (ISS), take a gander through our guide to life in orbit, where home is as little as 200 miles away but whizzes by 16 times a day.

We've brought in a pair of experts to bring you up to speed: Julie Robinson is Nasa's chief scientist for ISS, while Chris Hadfield became the most famous astronaut since Neil and Buzz during his second mission here as commander a couple of years ago (remember that Bowie cover?); nobody has described the wonder of what you're about to do quite like the moustachioed pilot from Ontario.

Moving in

“The first thing to do is get changed from your pressure suit into your flight suit,” says Hadfield. “Then there are two hatches. Open the Soyuz hatch then wait for the station crew to open theirs. As you know, there are usually six aboard the ISS, but there are only three up there at the moment – the Russians Sergey Volkov and Mikhail Korniyenko and the American Scott Kelly. In the Russian tradition, you don't shake hands across the threshold, as it's considered unlucky. Wait to be welcomed through and then shake hands. It will be a joyous meeting.”

You'll now be in the heart of ISS – the Russian Zvezda service module, which is the size of a big van. First things first: you guessed it, a safety briefing. You'll want to listen. Nobody has died up here, but there are a lot of ways it can happen – some quicker than others, none of them pleasant.

“Then you start moving in,” says Hadfield. “And that's fun. You need to transfer your sleeping bag into your sleep pod, which the last person should have cleaned and vacuumed and maybe left you a little welcome greeting. You'll see a cupboard with your name on it containing stuff sent up for you, including your clothing for the next six months. Put some pictures on the wall and make yourself at home.”

Alcohol and space travel generally don't mix, but there can be sober initiations for arrivals. “The existing crew might float water in the air and tell you to drink it,” Hadfield explains. “You can squeeze a ball of water as big as a tennis ball out of a drink bag, but as soon as it touches your lips it spreads over your whole face and doesn't go in your mouth.”

Above all, enjoy being up here and take pride in being the first British visitor to the ISS during its 15 years of continuous manned flight. “All of your simulations and dreams are suddenly real and right in front of you,” says Hadfield. “There's a bit of an Alice in Wonderland feel to it.” k

Getting around

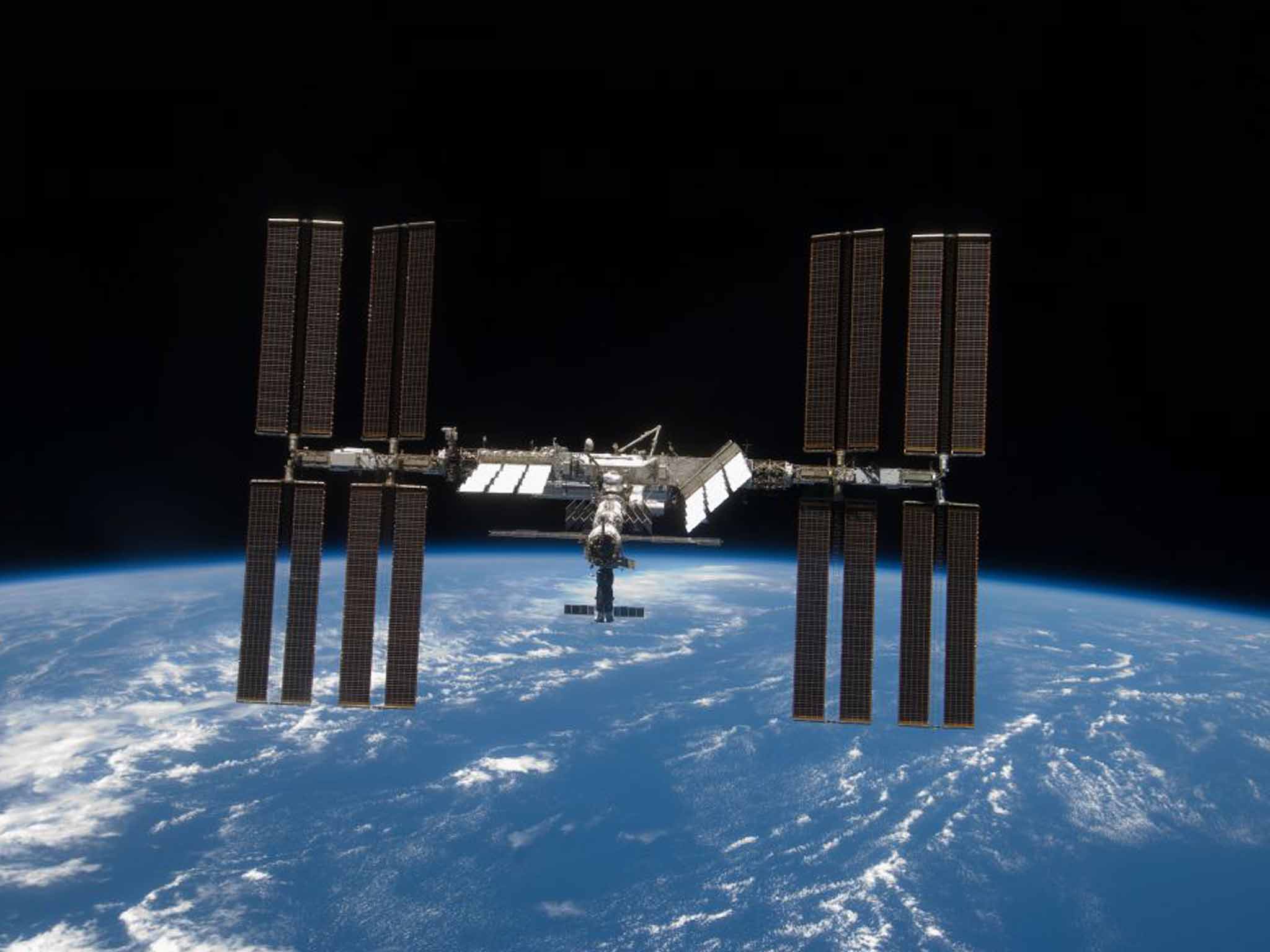

Hadfield describes ISS, which has roughly the living space of one-and-a-half jumbo jets, as “like a connected series of well-lit caves. Each is long and thin and they all go off at different angles. It's very disorienting, with no up or down, so in that way it's more like exploring a sequence of well-lit caves while scuba diving.”

More than a dozen pressurised modules are at the centre of the main truss, the tree trunk from which everything branches, including the sail-like solar arrays. Russian residents have two sleep pods in Zvezda, but the other four are in a module called Harmony. This opens on to the separate Japanese and European lab modules at the other end of the truss, which have – happily for you – better insulation for a quieter night.

But you'll have to get there first, says Hadfield, and, “It takes about a month to become truly graceful in weightlessness. At first you'll bump into things and gauge your speed wrong or build up too much momentum. It's very easy to break a finger. But after a while you get unconsciously good at it. Your feet naturally look for places to grab with the toes, like a monkey's tail. And right up until five minutes before you go home, it will still be fun. It's the toy that never winds down.”

You'll also have to get over some serious nausea. Take your meds and it will pass. Eventually. Otherwise the filtered air feels surprisingly fresh – there isn't much of a smell on board – and the hum of equipment, pumps and vents is as reassuring as a womb's din. If it's suddenly all quiet? “You're about to die.” Useful advice, there.

When you get your first spare moment, “Head past the treadmill and toilet, and get down into the floor,” Hadfield suggests. “As you pull yourself down, you're suddenly surrounded by glass. You're in the cupola and for the first time you're looking at Earth. It's too much at first; it's like walking into the Louvre at eight kilometres a second – you're going to miss things. But you'll spend a lot of time here trying to get to know our planet; this new understanding of our world will be the most profound part of your experience.”

The 9-to-5

Right, snap out of your reverie; you have work to do. “At any given time we have roughly 300 experiments active on ISS,” says Julie Robinson. “One experiment you'll be doing for the US lab involves lining cells that might be used to help repair damaged hearts. Cells in space can behave more like cells in the body than in a culture on Earth because they don't settle out with gravity.”

Similarly, you will also be studying the solidification of alloy samples without the interference of a container, as part of an experiment that could transform manufacturing processes. If that sounds dry, consider some of the scientific breakthroughs that have taken place up here. As Robinson says, “Countless lives have been saved during brain surgery that would not be possible without technology developed on ISS.”

Experiments will form the bulk of your working day. Robinson says astronauts have far more freedom to run their own schedules than they used to, but Hadfield describes a tight ship. “On your laptop you'll find the mission schedule. Each crew member has a row divided into five-minute increments showing what you do each day for six months. You might wake up and say, OK, it's 8:04, I need to go to the bathroom then eat, shower and do exercise then work on an experiment, then call Earth.”

If you're really lucky, you'll be called on to do a spacewalk: some repairs to the power and thermal systems may be conducted in January. So keep your fingers crossed because, as Hadfield, a veteran of two spacewalks, says, “It's the most visceral of all the space experiences, to be alone in the universe.” k

Staying alive

The treadmill and a “weights” machine aren't here for fun. Without exercise in microgravity, “A healthy astronaut can lose up to 3 per cent of bone density every month, or as much as a woman with osteoporosis loses in a year,” Robinson warns.

You'll eat surprisingly well, choosing three meals and a snack each day, all served in rehydration bags. Hadfield recommends the prawns in a spicy horseradish sauce. “Eating in space is like eating with a head cold,” he says. “But this has a real bite.”

Being on the American side of the station, you'll drink water filtered from condensate, washing and – yes – urine. The Russians have a separate filtration system that does not use urine, but you will drink theirs, which they helpfully carry through the ship in bags from their toilet.

If you think it's going to be hard to survive up here so long, don't worry: you'll be too busy to miss home. “You're about to enter an immensely demanding place,” Hadfield says. “You can be working 6am to midnight seven days a week. And on any given day you could be working with magnetically suspended particles in fluid, then get on the exercise equipment, then you're talking to the Prime Minister before you're repairing a $1bn bit of equipment.

It's immensely varied, but above all fun – you'll laugh all the time with the raw childlike joy of just being here.“

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments