Hurricane Fish: Deadly storm would still not have been predicted with today's supercomputers, study finds

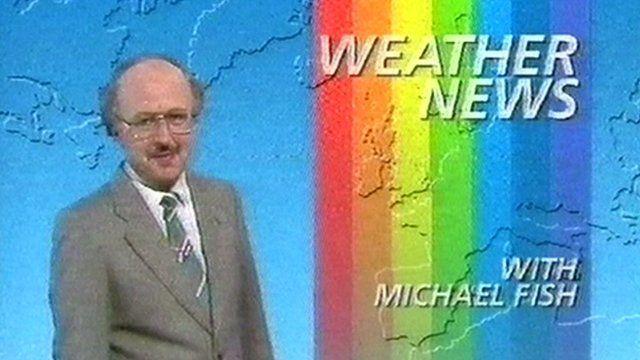

It's 30 years since Michael Fish's infamous broadcast – which saw him say the deadly storm was nothing to worry about

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Fish still wouldn't have been able to see the true scale of the Great Storm of 1987, according to a new study.

Modern technology would have allowed the weatherman to see the storm was coming. But it would still have been very difficult to track.

Mr Fish became famous when he scoffed at the idea that a hurricane was coming to the UK and told viewers not to worry. Just hours after, the once-in-a-century storm arrived and killed 18 people, as well as causing £1 billion of damage.

The new study found that even the Met Office's incredibly advanced supercomputer – which can perform 14,000 trillion calculations per second – would have had difficulty tracking it. It would have been able to see the storm, but not entirely.

However, scientists admitted the storm would have been difficult to track even with the help of multiple computer simulations and billions of satellite images.

According to the supercomputer models, there would have been indications of the weather system changing course and heading south towards France a day before it struck the UK.

Michael Fish might have been saved from serious embarrassment but would probably not have got everything right.

Met Office meteorologist and TV weather presenter Alex Deakin said he thought the looming storm would have merited an amber - not a red - hazard warning using the colour-coded system introduced in 2007.

Speaking on the 30th anniversary of the storm that blasted in from the Bay of Biscay on the night of Thursday, October 15, he said: "On the Sunday there's every chance there would have been a yellow warning at that stage.

"Leading up to it (the storm) on the Monday and Tuesday, we probably would have named the storm.

"Then, on the Wednesday ... you'd have been talking about, well actually, it looks like it's shifting further south. Stay tuned to the forecast, keep up to date.

"There's still a risk of it, it's just that that risk had reduced, because it now looked as if it was going more towards France.

"That's the kind of thing that would have happened. Hindsight's a wonderful thing."

The National Severe Weather Warning service was set up by the Met Office in the wake of the Great Storm in 1988.

From 2011 it switched from a threshold-based system, delivering warnings when wind or rain of sufficient intensity was predicted, to one based on impact that took account of timing and environmental conditions.

One reason why the 1987 storm flattened an estimated 15 million trees was that the ground was wet, making them easier to fell.

In the last three years the system of naming medium and high impact storms was brought in.

Asked at a press briefing in London what the Great Storm might have been named, Met Office expert Sarah Davies quipped: "Michael".

At the time Mr Fish made his famous forecast, satellite images were blurry and not even used in computer models, which relied on measurements and observations from ships, aircraft and weather-watching buoys.

In 1987 very little information was available from the storm's birth place in the Bay of Biscay.

A typical smartphone today has at least five times more processing power than the Met Office computer did three decades ago, said the experts.

Ken Mylne, head of verification at the Met Office, said weather forecasting had been "totally transformed" since then.

He added that even today, a storm identical to the one Michael Fish failed to predict would present a challenge.

"There would still be a degree of uncertainty, particularly in the local detail - where the strongest winds might be," said Mr Mylne.

"Some storms are very predictable and you can be more confident; others like this one are more difficult."

The storm involved an unusual combination of forces, including a kink in the jet stream funnelling air through a narrow corridor high in the atmosphere and pockets of high-speed wind known as "jet streaks".

It also featured a very rare violent event known as a "sting jet" that was only recognised in 2004 by scientists analysing the effects of the 1987 storm.

A sting jet is a downward burst of intense wind that originates in a band of cloud wrapped around a cyclone. Covering an area up to 50 kilometres wide, it can generate destructive gusts of 100mph or more.

The strongest gust recorded in the 1987 storm occurred in Shoreham-by-Sea, west Sussex, and reached 115 mph. At that point, the anemometer instrument used for measuring wind speed broke.

London was hit by 94mph gusts that ripped roofing slates off houses and overturned cars.

The storm, which left hundreds of thousands of homes without power, was the most damaging since 1703. In addition to the lives lost in the UK, it killed another four people in France.

In his lunchtime BBC broadcast on October 15, Mr Fish said: "Earlier on today apparently, a woman rang the BBC and said she'd heard there was a hurricane on the way. Well, if you are watching, don't worry, there isn't."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments