How to hunt a giant sloth – according to ancient human footprints

How we discovered ancient footprints of early human hunters and their megafauna prey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rearing on its hind legs, the giant ground sloth would have been a formidable prey for anyone, let alone humans without modern weapons. Tightly muscled, angry and swinging its forelegs tipped with wolverine-like claws, it would have been able to defend itself effectively. Our ancestors used misdirection to gain the upper hand in close-quarter combat with this deadly creature.

What is perhaps even more remarkable is that we can read this story from the 10,000-year-old footprints that these combatants left behind, as revealed by our new research published in Science Advances. Numerous large animals such as the giant ground sloth – so-called megafauna – became extinct at the end of the Ice Age. We don’t know if hunting was the cause, but the new footprint evidence tells us that human hunters clearly did tackle such fearsome animals and the way in which they did it.

These footprints were found at White Sands National Monument in New Mexico, US, in an area used by the military. The White Sands Missile Range, located close to the Trinity nuclear site, is famous as the birthplace of the US space programme, of Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars initiative and of countless missile tests. It is now a place where long-range rather than close-quarter combat is fine-tuned.

It is a beautiful place, home to a huge salt playa (dry lake) known as Alkali Flat and the world’s largest gypsum dune field, made famous by numerous films including Transformers and The Book of Eli. At the height of the Ice Age it was home to a large lake (Lake Otero).

As the climate warmed, the lake shrank and its bed was eroded by the wind to create the dunes and leave salt flats that periodically pooled water. The Ice Age megafauna left tracks on these flats, as did the humans that hunted them. The tracks are remarkable in that they are only a few centimetres beneath the surface and yet have been preserved for over 10,000 years.

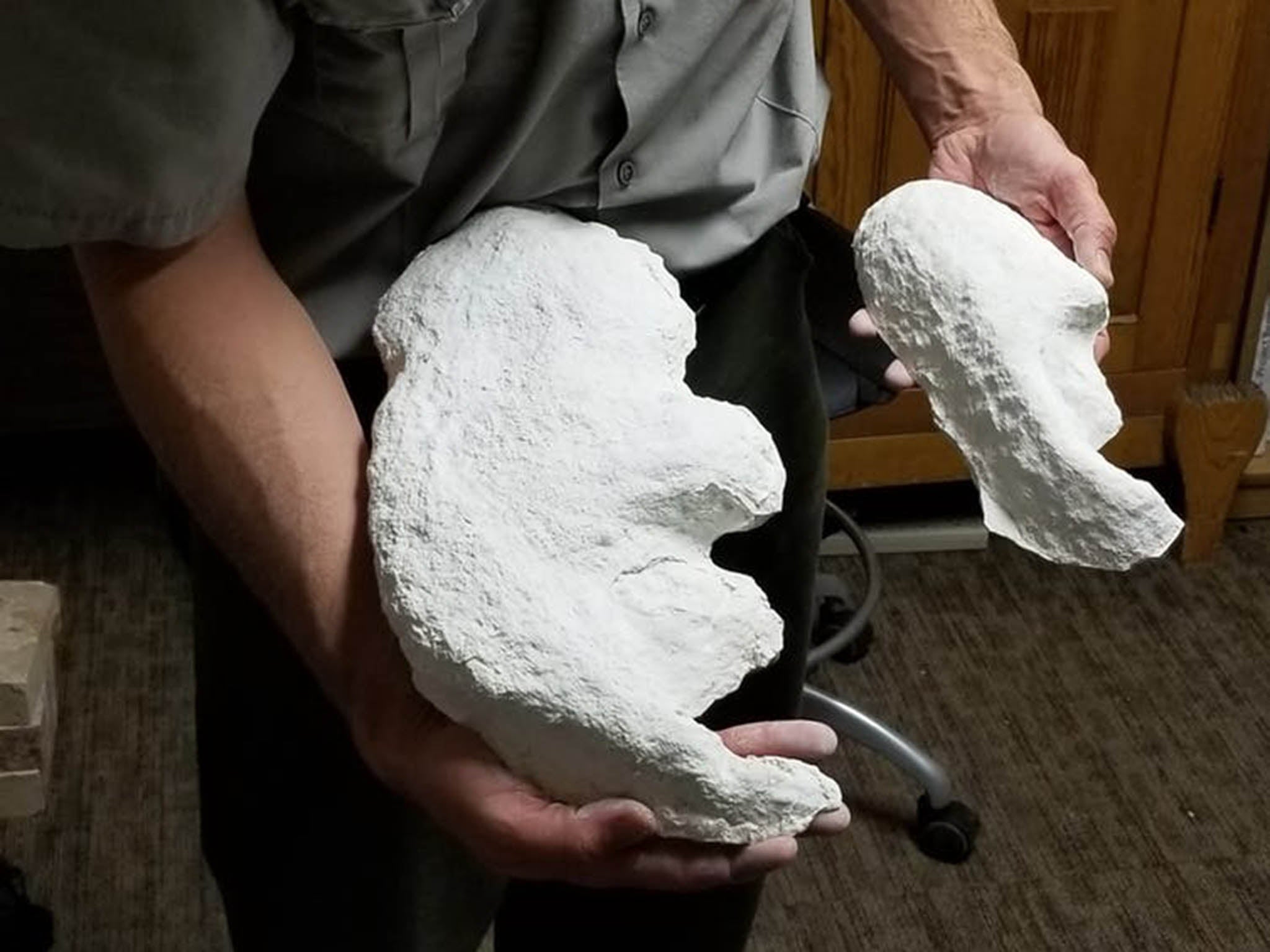

Here there are tracks of extinct giant ground sloths, mastodons, mammoths, camels and dire wolves. These tracks are colloquially known as 'ghost tracks' as they are only visible at the surface during specific weather conditions, when the salt crusts are not too thick and the ground not too wet. Careful excavation is possible in the right conditions and reveals some amazing features.

Perhaps the most remarkable of these is a series of human tracks that we found within the sloth prints. In our paper, produced with a large number of colleagues, we suggest that the humans stepped into the sloth prints as they stalked them for the kill. We have also identified large 'flailing circles' that record the sloth rising up on its hind legs and swinging its fore legs, presumably in a defensive, sweeping motion to keep the hunters at bay. As it overbalanced, it put its knuckles and claws down to steady itself.

These circles are always accompanied by human tracks. Over a wide area, we see that where there are no human tracks, the sloths walk in straight lines. Where human track are present, the sloth trackways show sudden changes in direction, suggesting the sloth was trying to evade its hunters.

Piecing together the puzzle, we can see how sloths were kept on the flat playa by a horde of people who left tracks along its edge. The animals was then distracted by one stalking hunter, while another crept forward and tried to strike the killing blow. It is a story of life and death, written in mud.

What would convince our ancestors to engage is such a deadly game? Surely the bigger the prey, the greater the risk? Maybe it was because a big kill could fill many stomachs without waste, or maybe it was pure human bravado.

At this time at the end of the last Ice Age, the Americas were being colonised by humans spreading out over the prairie plains. It was also a time of animal extinctions. Many palaeontologists favour the argument that human over-hunting drove this wave of extinction and for some it has become an emblem of early human impact on the environment. Others argue that climate change was the true cause and our species is innocent.

It is a giant crime scene in which footprints now play a part. Our data confirms that human hunters were attacking megafauna and were practiced at it. Unfortunately, it doesn’t cast light on the impact of that hunting. Whether humans were the ultimate or immediate cause of the extinction is still not clear. There are many variables including rapid environmental change to be considered. But what is clear from tracks at White Sands is that humans were then, as now, 'apex predators' at the top of the food chain.

Matthew Robert Bennett is a professor of environmental and geographical sciences, Katie Thompson is a research associate and Sally Christine Reynolds is a senior lecturer in hominin palaeoecology at Bournemouth University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments