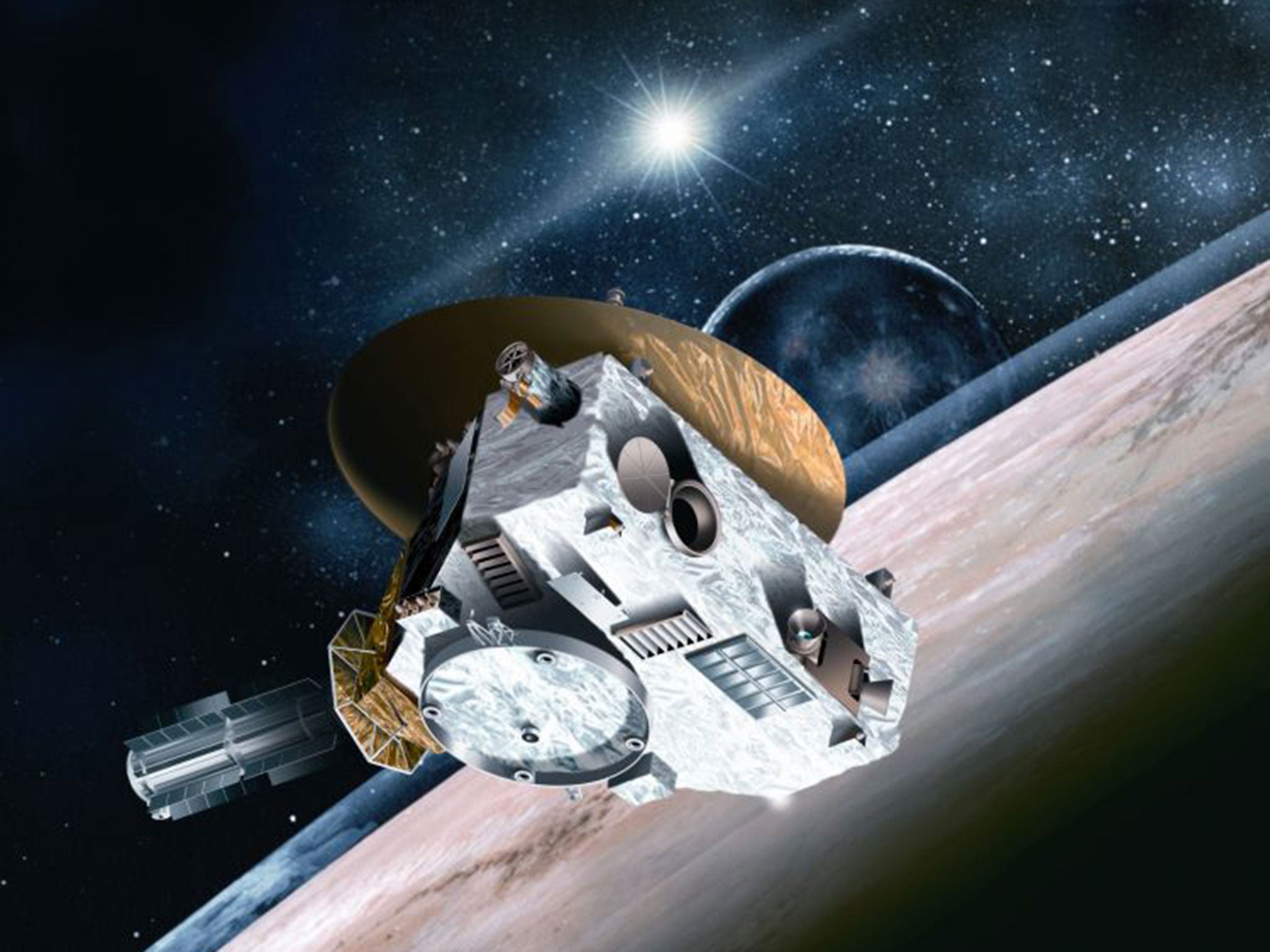

How Nasa's New Horizon got over its 'Apollo 13' moment on the way to Pluto

No lives were in danger, but that didn't make the 'anomaly' on 4 July any less intense

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The people in the Mission Operations Centre — "the MOC" — had been tracking Nasa’s New Horizons spacecraft for 9½ years as it journeyed the breadth of the solar system. It was just 10 days away from the dwarf planet Pluto when, at 1:55 pm on July 4, it vanished.

Gone.

“OUT OF LOCK,” a computer screen declared.

No more data, no connection at all. As if the spacecraft had plunged into a black hole. Or hit an asteroid and disintegrated.

Mission Operations manager Alice Bowman called the project manager, Glen Fountain, who was spending the afternoon of July 4 at home.

“We just lost telemetry,” she told him.

He raced to the MOC, in the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Also arriving within minutes was the mission’s leader, Alan Stern, a planetary scientist. Everyone cancelled July 4 plans. They weren’t going home tonight. This was a sleep-on-the-office-floor crisis.

“I stayed on the floor, and it was probably one of the best 15- or 20-minute sleeps I’ve ever had,” Bowman says.

The official story from Nasa and APL officials over the next two days was this was an “anomaly,” and the team had resolved the issues and gotten the spacecraft back in shape for the Pluto flyby. But this was no mere glitch. This was almost a disaster. This was, as Stern would later admit, “our Apollo 13.”

The disappearance of the spacecraft challenged the New Horizons team to perform at its highest level and under the greatest of deadline pressures.

The nature of the New Horizons mission did not permit any wiggle room, any delays, any do-overs, because it was a flyby. The spacecraft had one shot at Pluto, tightly scheduled: When it vanished, New Horizons was going about 32,000 miles per hour and on track to make its closest pass to Pluto, about 7,800 miles, at precisely 7:49 am July 14.

But as the New Horizons team gathered in the control room on July 4, no one knew whether their spacecraft was still alive.

The scene of all this drama is a place with a proud history but a remarkably low profile. Raise your hand if you’ve heard of the Applied Physics Laboratory. Raise the other hand if you’ve heard of its slogan, “Critical Contributions to Critical Challenges.”

It’s a sprawling place, hidden in plain sight just west of Route 29 between Washington and Baltimore. The campus has 20 major buildings on 453 acres. It has 5,000 full-time and 400 part-time employees, making it the largest employer in Howard County.

But its staff can’t discuss many specifics. The stealthy nature of the lab reflects its heavy load of classified research. Major funders include the military (the Navy, in particular), the Department of Homeland Security and the intelligence community.

APL was established during World War II and originally housed in a used-car dealership in Silver Spring. It has racked up a long list of technological achievements including missile guidance and satellite-based navigation. Researchers here today are finding ways to protect soldiers from blast injuries. They have created a prosthetic arm with 26 joints and 17 motors that can curl 45 pounds, tweeze 20 pounds between two fingers and be controlled entirely by brain signals.

When people think of a lab that makes robotic probes that explore the solar system, they usually think of Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. But APL has a boutique spaceflight operation funded by Nasa contracts, accounting for about 20 per cent of the lab’s overall workload. APL has built and operated 68 spacecraft over the years, including the Messenger spacecraft that recently explored Mercury. But despite many successes, APL has never had a mission guaranteed to get as much media coverage as New Horizons.

“This is a big deal,” says Ralph Semmel, the director of APL.

Because New Horizons is so far away, it takes 4 1/2 hours for a one-way message between the spacecraft and the MOC. That means whatever happened to New Horizons on July 4 had actually happened 4 1/2 hours before the people in Mission Operations knew about it.

That also meant that any instructions to the spacecraft would take 4 1/2 hours to get there.

This wasn’t like talking to a robotic vehicle parked on the moon; a signal there or back takes little more than one second.

The team in the MOC knew that one possibility, very remote, was that the spacecraft had hit something. It’s going so fast that it could be disabled by a collision with something as small as a grain of rice. But there’s no rice near Pluto and, although there are dust particles, rocks, boulders and a few moons, space is really spacious in three dimensions. The odds of New Horizons hitting anything during this journey — especially while still millions of miles from the Pluto system — are extremely low.

“That would be extraordinarily bad luck,” project manager Fountain said.

Still, with the spacecraft lost at the edge of the solar system, no one knew what had happened or whether they would ever hear from it again.

They ran through the most likely causes of the anomaly. They had two fairly simple scenarios. The first was that, for some reason, the main computer had rebooted itself. That had happened a few times in the past.

The second scenario was that the spacecraft sensed something amiss and, as it is programmed to do, powered down the main computer and switched operations to the backup computer. That had never happened before.

If the backup computer had, in fact, taken over communications with Earth, it would use a slightly different radio frequency and transmission rate.

The APL team decided to check that second scenario straightaway. The team sent a new set of instructions to Nasas Deep Space Network — the trio of huge radio antennas in California, Spain and Australia that are responsible for communicating with New Horizons and many other spacecraft. The dish in Australia began searching for New Horizons at the new frequency.

Everyone waited.

Three o’clock came and went.

At 3:11 p.m., one word flashed on screen in the MOC.

“LOCKED.”

The big dish and New Horizons had established a radio handshake, with data following almost immediately.

Bowman thought: Thank God, the spacecraft’s there, it’s alive.

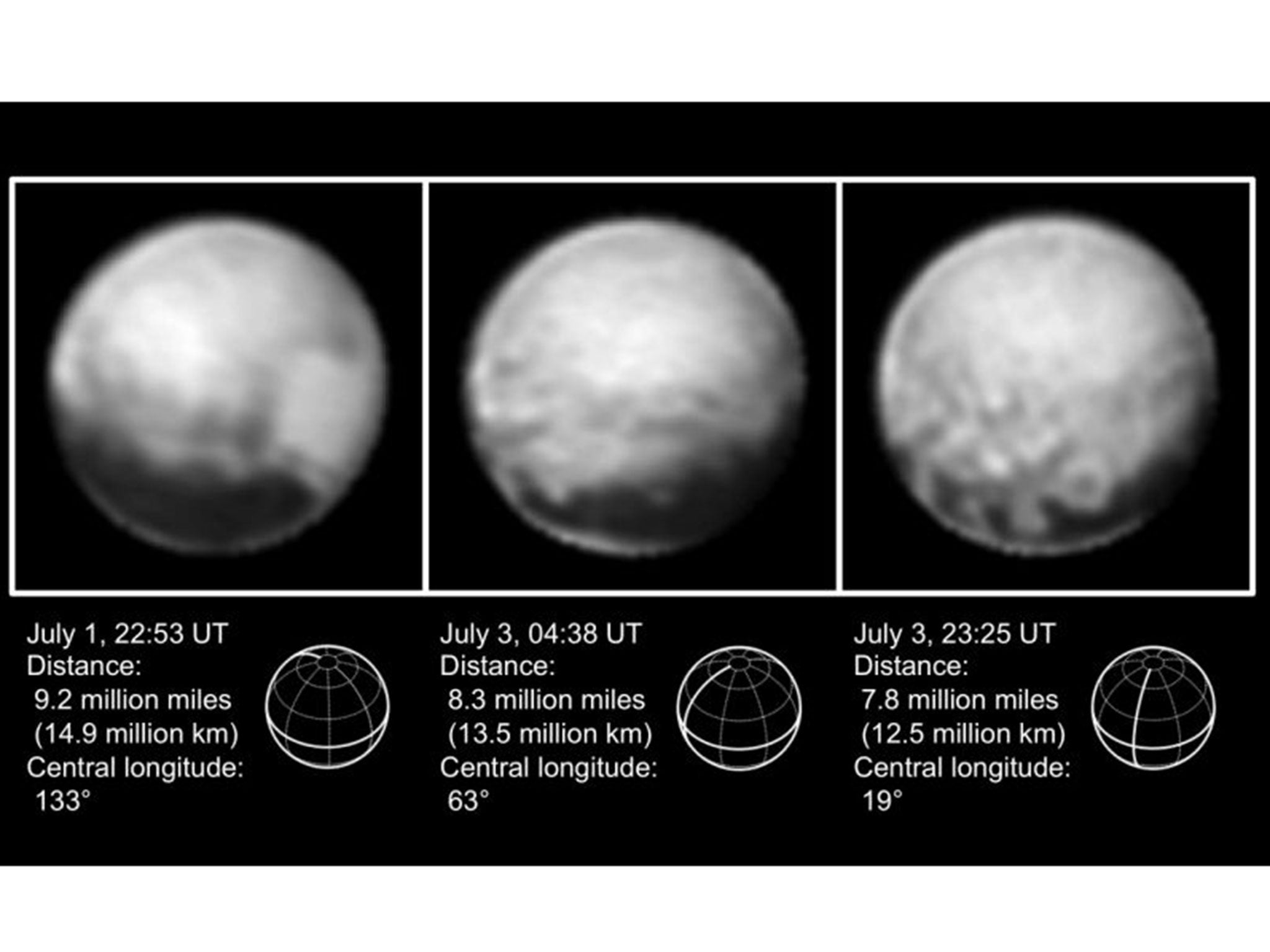

The crisis was hardly over. New Horizons had gone into safe mode. That involves shutting down instruments and noncritical systems. The spacecraft also automatically turns back toward Earth and goes into a controlled spin of five revolutions per minute. The spinning makes navigation easier, but it also makes most scientific observations impossible. A spinning New Horizons could not take photos of Pluto.

The team figured out what had gone wrong. The spacecraft’s main computer had been compressing new scientific data for downloading much later. At the same time, it was supposed to execute some previously uploaded commands. It got overloaded; the spacecraft has an “autonomy” system that can decide what to do if something’s not quite right. That system decided to switch from the main to the backup computer and go into safe mode.

The spacecraft had been in safe mode before — but this was terrible timing. They were just days from Pluto.

“We were down to the wire,” Bowman said.

No one on the team got angry or lost his or her poise, she said: “All of us, I think, were feeling terrible that this had happened, but we were focused solely on getting that spacecraft back into an operational state so that we could do this flyby.”

On Twitter, anyone following the mission July 4 learned of the “anomaly.”

An official New Horizons account (@NewHorizons2015) offered an elliptical statement: “New Horizons in safe mode. We’re working it folks.”

The APL team had to reconfigure New Horizons the way you would rouse a drunk on a Sunday morning to get him ready for church. This required many commands, everything made slower by the nine-hour round-trip communication challenge across the 3 billion miles of space. Bowman slept on her office floor a second night on Sunday.

One key decision: return control of the spacecraft to the main computer. They trusted the main computer, knew its quirks, had tested it repeatedly — unlike the backup computer. Their plan didn’t require them to ask the main computer to do the kind of heavy-duty work that caused the glitch Saturday.

On Tuesday morning, July 7, the New Horizons team returned their spacecraft to no-spin mode and prepared it for the Pluto encounter.

This period of reconfiguration was a bit nerve-racking inside the MOC, because it required another blackout period of an hour and 15 minutes as the spacecraft lost contact with the ground.

At 10:21 am Tuesday, the spacecraft popped back up on the screen — healthy, on track, wide awake. At 12:30 p.m. Tuesday, New Horizons began executing the encounter sequence as programmed.

Huge relief at APL: On to Pluto!

In a news briefing Monday afternoon, with the recovery process ongoing, Stern had described the “anomaly” of July 4 as “a speed bump.” He and his colleagues downplayed the distressing nature of the event. That’s standard procedure for engineers and scientists: Admit no alarm. Proclaim competence and preparedness.

But in an e-mail later, Stern compared the incident to Nasa’s most famous emergency: “No lives were at stake, but in terms of mission success and time criticality, this was our Apollo 13. And it was our spacecraft and operations team’s finest hour.”

As she stood this week in the MOC, a few feet from a mural declaring “The Year of Pluto,” Bowman acknowledged the obvious: “It was very intense.”

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments