How I discovered the origins of the cigar-shaped alien 'asteroid' 'Oumuamua

In 2017, a mysterious, cigar-shaped object traversed our solar system. Its speed and orbit indicated it had originated from outside our galaxy. Now, Fabo Feng thinks he knows where

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

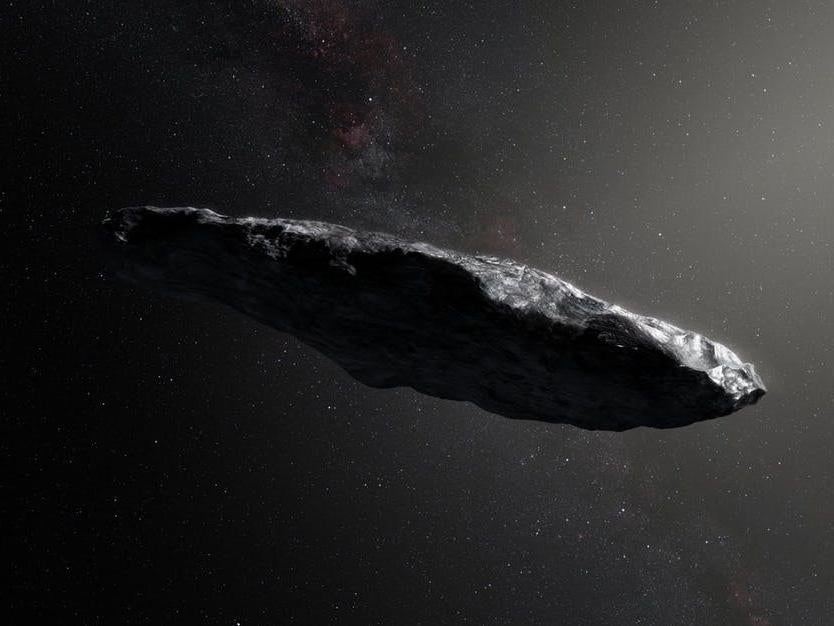

Your support makes all the difference.One of the highlights of 2017 was the discovery of the first object in our solar system that definitely came from somewhere else. At first we thought it was a comet, then an asteroid, and now the International Astronomical Union has reclassified it as something new entirely: An interstellar object. The Hawaiian astronomers who discovered it aptly named it ‘Oumuamua, which means “a messenger from afar arriving first”, reflecting that this object is like a scout sent from the past to reach out to us.

Research has already helped us learn a lot about ‘Oumuamua’s rare cigar-like shape, what it’s made of (ice with a carbon-rich surface) and its highly unusual orbit, which will take it out of our solar system at a speed of around 26km/s. The Breakthrough Listen research programme has even investigated whether ‘Oumuamua is an alien space ship by scanning the object for life forms with the Green Bank telescope. No intelligent signals have been identified so far, though further observations are planned.

Now my latest study gives us a glimpse of exactly where ‘Oumuamua may have come from. Reconstructing the object’s motion, my research suggests it probably came from the nearby “Pleiades moving group” of young stars, also known as the “Local Association”. It was likely ejected from its home solar system and sent out to travel interstellar space.

Based on ‘Oumuamua’s trajectory, I simulated how it has probably travelled through the galaxy and compared this to the motions of nearby stars. I found the object passed 109 stars within a distance of 16 light years. It went by five of these stars from the Local Association (a group of young stars likely to have formed together) at a very slow speed relative to their movement.

It’s likely that when ‘Oumuamua was first ejected into space, it was travelling at just enough speed to break away from the gravity of its planet or star of origin, rather than at a much faster speed that would require even more energy. This means we’d expect the object to move relatively slowly at the start of its interstellar journey, and so its slow encounters with these five stars suggests it was ejected from one of the group.

When was it kicked out of its home?

Stars typically move with an average speed when they are formed and gradually change speed as they encounter very large objects, such as massive stars and molecular clouds and are affected by their gravity. Unlike most nearby stars, ‘Oumuamua moves very slowly compared to the average motion of the rest of the galaxy. This suggests it has only been travelling in interstellar space for a relatively short time and hasn’t had a chance to encounter many massive objects that would speed it up.

We also have evidence for ‘Oumuamua’s relatively young age from the colour of its surface. Outside of the protection of a star’s magnetic field, objects in space are bombarded with cosmic rays and interstellar dust and gas that gradually alter their surfaces and turn them very red in colour. But ‘Oumuamua has a more neutral colour, suggesting it has only been impacted by cosmic rays for, at most, hundreds of million years rather than for the billions of years that our solar system has existed.

How was it ejected?

‘Oumuamua is extremely elongated and has quite a different shape from other objects in our solar system. It was probably formed by a relatively high-energy process, such as a collision, or ejected from a forming star. Most objects in the outer part of a planetary system are made more of ice and most objects in the inner regions are made more of rocks. Since ‘Oumuamua is a more even mix of ice and rocks, it’s likely it came from the middle part of a solar system, similar to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter that features a mixture of icy and rocky asteroids.

Perhaps the most plausible scenario is that ‘Oumuamua was ejected from a closely separated binary star system made of two stars closely orbiting each other. Objects orbiting one of the stars in a binary system will be strongly affected by the gravity of the other and so can be more easily ejected from the system than if it had just one star.

‘Oumuamua is probably just the tip of the iceberg. My research suggests there are likely more than 46 million similar interstellar objects crossing the solar system every year. Most of them will be too far away for us to see with our current telescopes. But new telescopes and surveys should soon be able to find these interstellar messengers, which may be sending us important information about how stars and planets are formed. Studying more objects like ‘Oumuamua will enable us to work out how much debris is left over from star formation and how much this adds to the mass of our galaxy.

Another reason to study these interstellar objects is that they could one day threaten to collide with the Earth and cause catastrophic events such as mass extinctions. The more we know, the better prepared we’ll be if that day ever comes.

Fabo Feng is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Hertfordshire. This article was originally published on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments