How cute things hijack our brains and drive behaviour

Researchers from the University of Oxford say that cuteness may be one of the strongest forces that shape our behaviour – potentially making us more compassionate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is the cutest thing you have ever seen? Chances are it involves a baby, a puppy or another adorable animal. And chances are it is forever imprinted on your mind. But what exactly is this powerful attractive force and how is it expressed in the brain?

Together with our colleagues Marc Bornstein from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Catherine Alexander from the University of Oxford, we have reviewed the existing research on the topic and discovered that cuteness is more than something purely visual. It works by involving all the senses and strongly attracting our attention by sparking rapid brain activity. In fact, cuteness may be one of the strongest forces that shape our behaviour – potentially making us more compassionate.

Babies are designed to jump to the front of the queue – our brain-processing queue, that is. They get ahead of everything else going on in our minds, which makes them difficult to ignore. They also grab our attention even before we have time to recognise that they are babies. They do it by being cute.

Babies not only look cute, with their big eyes, chubby cheeks and button noses, their infectious laughs and captivating scent also make them sound and smell cute. Their soft skin and chubby limbs may even make them feel cute. Together, these aesthetic qualities act as a crucial mechanism that enables babies to attract us through all our senses. Babies need constant attention and care to survive, and cuteness is one of the main ways they get it.

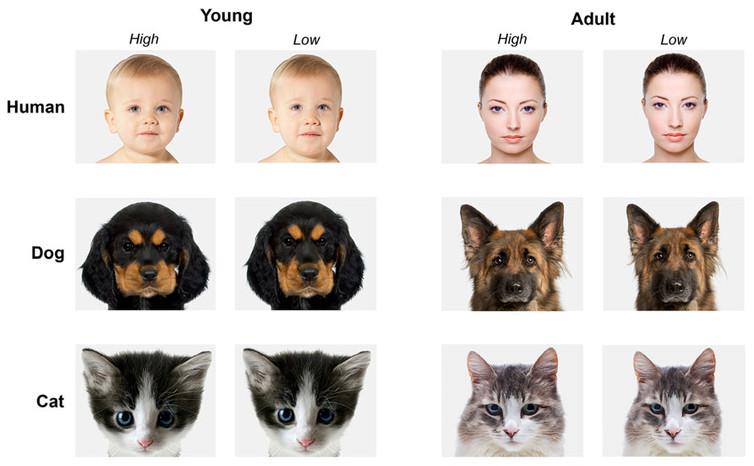

This nurturing instinct could even be driving our wider perception of cuteness – research has shown that we typically feel affection for animals with juvenile features. Dogs, for instance, have been bred to have similar features to babies, with big eyes, bulging craniums and recessed chins. They are also soft to touch. Whether we want it or not, we may also feel a certain affection for adults and even inanimate objects with infant-like features such as dolls, teddies and even miniature products.

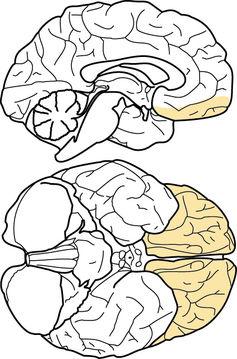

Cuteness may help to facilitate well-being and complex social relationships by activating brain networks associated with emotion and pleasure and triggering empathy and compassion. When we encounter something cute, it ignites fast brain activity in regions such as the orbitofrontal cortex, which are linked to emotion and pleasure. It also attracts our attention in a biased way: babies have privileged access to entering conscious awareness in our brains.

As a result, we like looking at babies and other cute things. Research has shown that people would rather look at cute baby faces than adult faces and that they would rather adopt or give a toy to babies with cuter faces. Studies have also shown that even babies and children prefer cute baby faces and that cuteness affects both men and women, even if they are not parents. Cute babies also spur us to action: research reveals that people will expend extra effort to look longer at cute baby faces.

Neuroimaging research has shown that in adults, the orbitofrontal cortex becomes active very quickly – 140ms or a seventh of a second – after seeing a baby face. The orbitofrontal cortex is strongly involved in orchestrating our emotions and pleasures, so its rapid activity may partly explain how babies appropriate our attention so quickly and completely.

Cuteness also initiates a response that happens much more slowly. The initial fast attention triggers slower, more sustained processing in large brain networks. This kind of brain activity is associated with complex behaviours involved in the caregiving and bonding that are the hallmarks of parenting. Caring for a baby calls for a set of skills that take time to acquire and hone, and this slow attainment of expertise changes the caregiver’s brain. This kind of considered behaviour cannot be reduced to the fast, instinctual rapid reaction to cuteness.

Parenting is a good example of how cuteness can trigger slow, sustained brain processing in networks associated with emotion, pleasure and social interactions. Still, as shown by our interest not only in our own infants but in other infants and baby animals, cuteness can help trigger empathy and compassion beyond parenting. Activating this network of brain activity may also enable cuteness to boost moral concern by expanding the boundary around what we regard as worthy of moral consideration. For example, an image of a cute infant or baby animal can help charities nudge us to donate more money.

Research on cuteness could also help us to understand how problems in parent-child bonding arise, such as following postpartum depression or an infant being born with a cleft lip and palate. We know these things can disrupt caregiving by changing how people process signals from babies.

Both parental depression and infant cleft lip are associated with developmental difficulties in infants. These conditions are relatively common: postpartum depression affects 10-15 per cent of parents in high-income countries and up to 30 per cent in middle- and low-income countries. Cleft lip affects one in 700 live births in the UK. A better understanding of how we succeed and sometimes fail to receive and interpret baby signals that are crucial for caregiving may help us to develop better treatments for families affected by problems such as these.

We are currently developing early interventions to help increase caregivers’ ability to properly interpret infant signals and provide appropriate responses. We have developed a “baby-social-reward-task” to do this, where participants learn about the temperament of infants through the use of emotional infant vocalisations and faces. Babies that were initially perceived as less cute became more cute through the positive feedback of infant laughter and smiles.

This article first appeared in The Conversation. Morten L Kringelbach, Alan Stein and Eloise Stark are academics at the University of Oxford

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments