Gotcha! How to swat a fly, and know that it will die

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

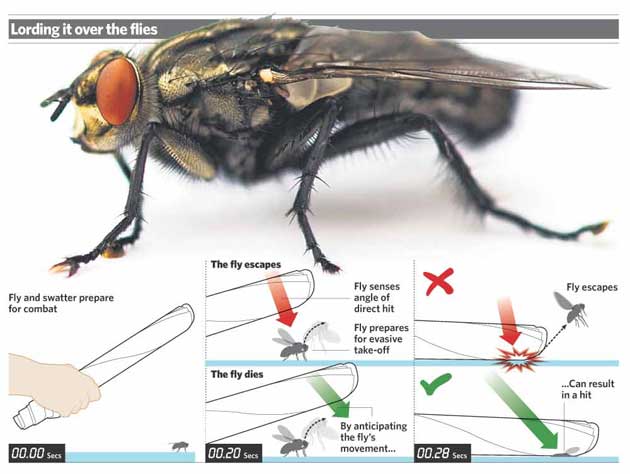

Your support makes all the difference.The enduring mystery of why it is so difficult to swat a fly has been solved by scientists who believe they can now offer technical advice on how to hit a fly before it has chance to escape.

A series of experiments with high-speed digital cameras and a swarm of obliging laboratory flies has discovered that the insects use a sophisticated defence system to anticipate a swatter's movements in a fraction of a second.

The researchers found that a fly can calculate the angle of attack, make appropriate movements to its body and legs and adjust its wings to allow it to evade a direct hit.

Professor Michael Dickinson of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said the findings offered a practical suggestion to anyone plagued by an annoying intruder in the kitchen. "It is best not to swat the fly's starting position, but rather to aim a bit forward of that to anticipate where the fly is going to jump when it first sees your swatter," he said.

Houseflies have all-round vision and can take off in any direction independently of how their body is aligned. This is one of the reasons why they are so good at evading an attack, Professor Dickinson said.

In the instant between seeing a moving swatter and flying away, the fly's brain is able to calculate the position of the impending threat and place its legs and body in an optimal position that allows it to jump in the opposite direction. All of the action is carried out within 100 milliseconds after the fly first spots the moving swatter, which shows just how rapidly the fly's brain can process the information, said Professor Dickinson.

He believes the fly must possess an internal map within its brain which converts the position of the threat into the appropriate body motion that leads to successful evasive action. "These movements are made very rapidly, within about 200 milliseconds, but within that time the animal determines where the threat is coming from and activates an appropriate set of movements to position its legs and wings," he said. "This illustrates how rapidly the fly's brain can process sensory information into an appropriate motor response."

The findings are published in the journal Current Biology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments