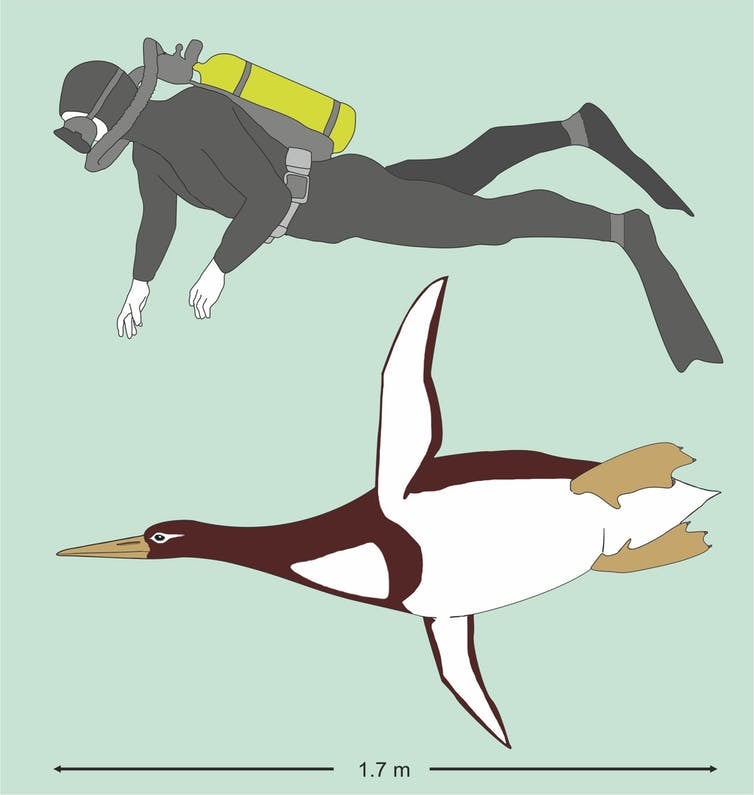

Giant penguin find: remains suggest huge bird was taller than a human

Scientists in New Zealand have discovered an extinct penguin known as Kumimanu biceae that was 1.77m tall

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have discovered a now-extinct species of giant penguin that was taller than most humans. The remains of the bird, perhaps the tallest penguin species ever discovered, help show how quickly giant penguins developed after the extinction of the dinosaurs around 66 million years ago.

The animal revealed by fossil fragments found in New Zealand was around 1.77m tall and weighed around 101kg. It would have dwarfed the largest penguin alive today, the emperor penguin, which measures 1.1m in height and 35kg in weight.

The skeletal remains from a single penguin included parts of the breastbone, shoulders, wings, legs and spine. Its notable features included an unusually thick sternal keel (part of the breast attached to the wings) and an unusually long femur (thigh bone).

These were enough to demonstrate the bird was not only a unique species but also a previously unknown genus (group of species). The species has been named Kumimanu biceae, from the Maori words “kumi”, referring to a large mythical monster, and “manu” meaning bird.

Living penguins all share a set of adaptations such as flipper-like wings, short and smooth feathers that trap air to aid buoyancy, and countershading (a black back and white front) to help avoid predators and increase their own hunting ability through camouflage. While we cannot be certain, it is likely that early penguins such as K biceae possessed at least some of these adaptations.

Penguin origins

There are currently between 17 and 20 species of penguins alive today, depending on the exact classification used, but there have been more species since the group first evolved some time after the dinosaurs went extinct. The earliest species of extinct penguin discovered so far is Waimanu manneringi, which lived in New Zealand around 62 million years ago. Although this species more closely resembled modern diver birds (or loons), it was already adapted for life in the water and couldn’t fly. Three of the earliest penguin fossils we have originated from southern New Zealand and Byrd Land, Antarctica, suggesting the birds first appeared in the southern hemisphere.

We previously thought that giant penguins took much longer to evolve. For instance, Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi and Pachydyptes ponderosus were for a long time considered to be the largest-ever penguins and lived during the Eocene epoch 56 million to 34 million years ago. But the discovery of K biceae suggests this size shift among penguins first occurred much earlier, shortly after the group became flightless during the Paleocene epoch, some 66 million to 56 million years ago.

This followed the mass extinction that wiped an estimated 75 per cent of life on Earth, including the dinosaurs. It is possible that the animals that survived the extinction were able to thrive and develop because their competitors and predators had disappeared. Many of these species evolved to become much larger, a tendency known as “Cope’s Rule”. Bigger animals are usually better at hunting, attracting a mate, retaining heat and can even be more intelligent.

In the case of penguins, the large reptile predators that dominated the seas during the time of the dinosaurs were wiped out, leaving space for K biceae and other early penguins to thrive. Once established, they probably grew increasingly large, following Cope’s Rule.

But they would have inevitably faced growing competition from other developing species. As large predatory toothed whales and seals evolved and succeeded, groups such as giant penguins would have no longer been able to compete and ultimately died out, leaving behind only the smaller species of penguins we recognise today.

Ben Garrod is a fellow in animal and environmental biology at the Anglia Ruskin University. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments