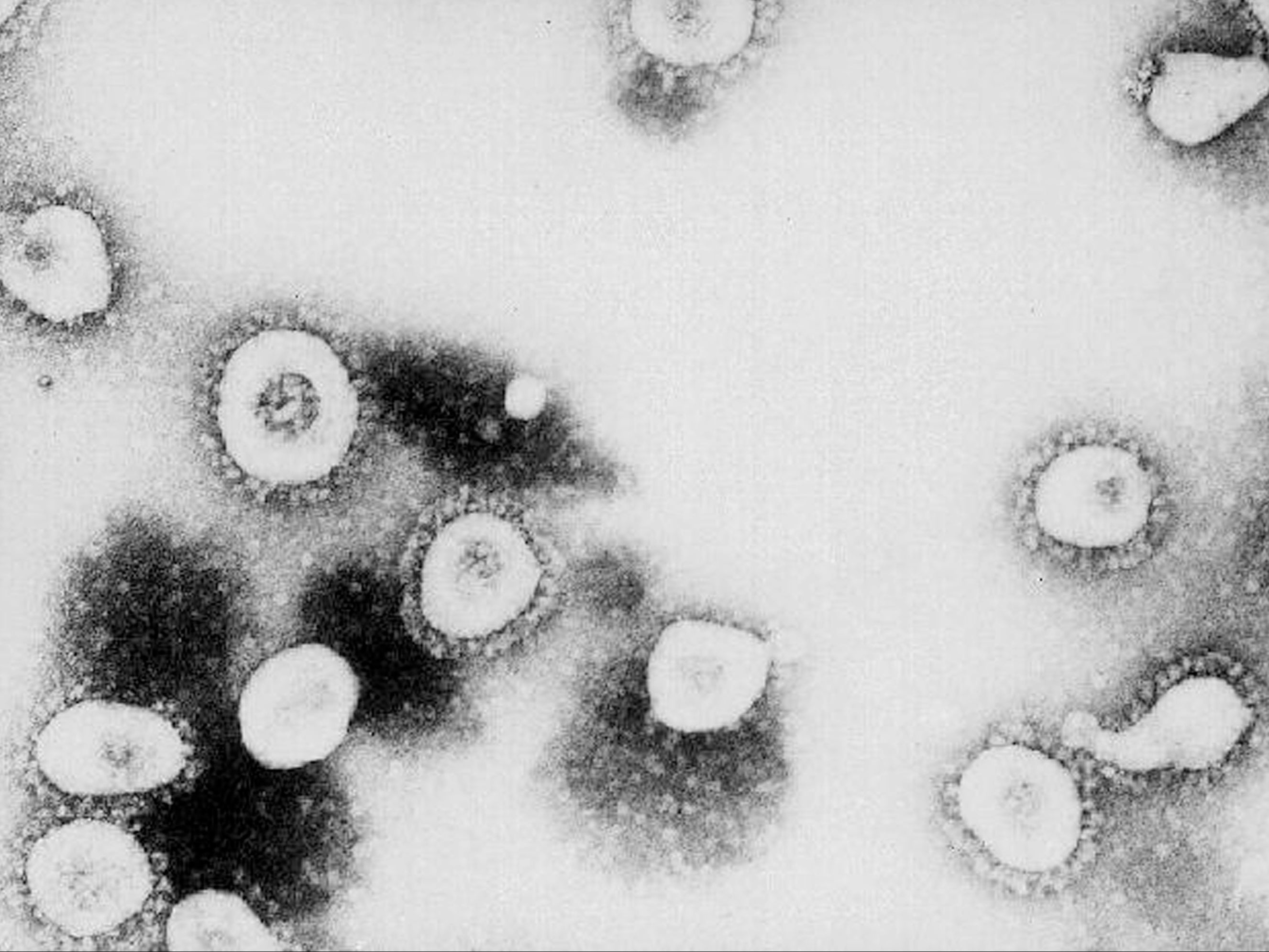

Scientists discover gene that can help shape immune response to Covid virus

Gene called OAS1 is thought to play key role in shaping individual’s response to Sars-CoV-2

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Small variations in the genetic make-up of an individual may help to explain why some people mount a strong natural defence against Covid infection, while others develop severe illness, according to a new study.

Scientists at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research have pinpointed a particular protein encoding gene, called OAS1, which is thought to play a key role in shaping the early stages of an individual’s response to Sars-CoV-2 – the virus that causes Covid-19.

When a human cell is infected, the OAS1 protein is able to sense the presence of the virus. It jumps into action, and kick-starts a chain of events linked to the activation of an RNA-killing enzyme, allowing the cell to start attacking the genetic material of the virus.

The study, published in the journal Science, suggests that some people express a more protective version of OAS1 that has been ‘prenylated’. This is the addition of a single molecule of lipid to the protein encoded for by the OAS1 gene.

Because coronaviruses hide inside cells and replicate their genomes inside vesicles formed out of lipid, the prenylated OAS1 is therefore better suited to seeking out Sars-CoV-2 and directing the cellular weaponry to attack it.

In hospitalised patients, the prenylated version of the gene was associated with better outcomes from severe Covid-19. Those without it had worse clinical outcomes in comparison; ICU admission or death was 1.6 times more likely in these patients, the study said.

The researchers also found that, approximately 55 million years ago, there was a removal of this protective gene in horseshoe bats – one of the presumed sources of SARS-CoV-2.

As such, this means the virus never needed to adapt to evade this particular line of defence, which therefore remains effective for some humans in providing protection.

But should Sars-CoV-2 mutate and acquire the ability to circumvent the defences generated by the prenylated OAS1 protein, the virus could potentially become more deadly or transmissible.

Professor Sam Wilson, a virologist at the Centre for Virus Research, said: “We know viruses adapt, and even Sars-CoV-2 has likely adapted to replicate in the animal reservoirs in which it circulates.

“Cross-species transmission to humans exposed the virus Sars-CoV-2 to a new repertoire of antiviral defences, some of which Sars-CoV-2 may not know how to evade.

“What our study shows us is that the coronavirus that caused the SARS outbreak in 2003 had already learned to evade prenylated OAS1 protein.

"If Sars-CoV-2 variants learn the same trick, they could be substantially more pathogenic and transmissible in unvaccinated populations. This reinforces the need to continually monitor the emergence of new Sars-CoV-2 variants.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments