Scientists regrow frog’s lost leg with experimental cocktail of drugs

After a 24-hour period of exposure to the drugs, a near fully-functional leg would grow in 18 months, Liam James reports

Frogs have been able to regrow lost legs through an experimental treatment, in what scientists say is a step towards eventual regenerative medicine in humans.

Many animals, such as salamanders, can naturally regrow limbs using stem cells. Frogs are not among them.

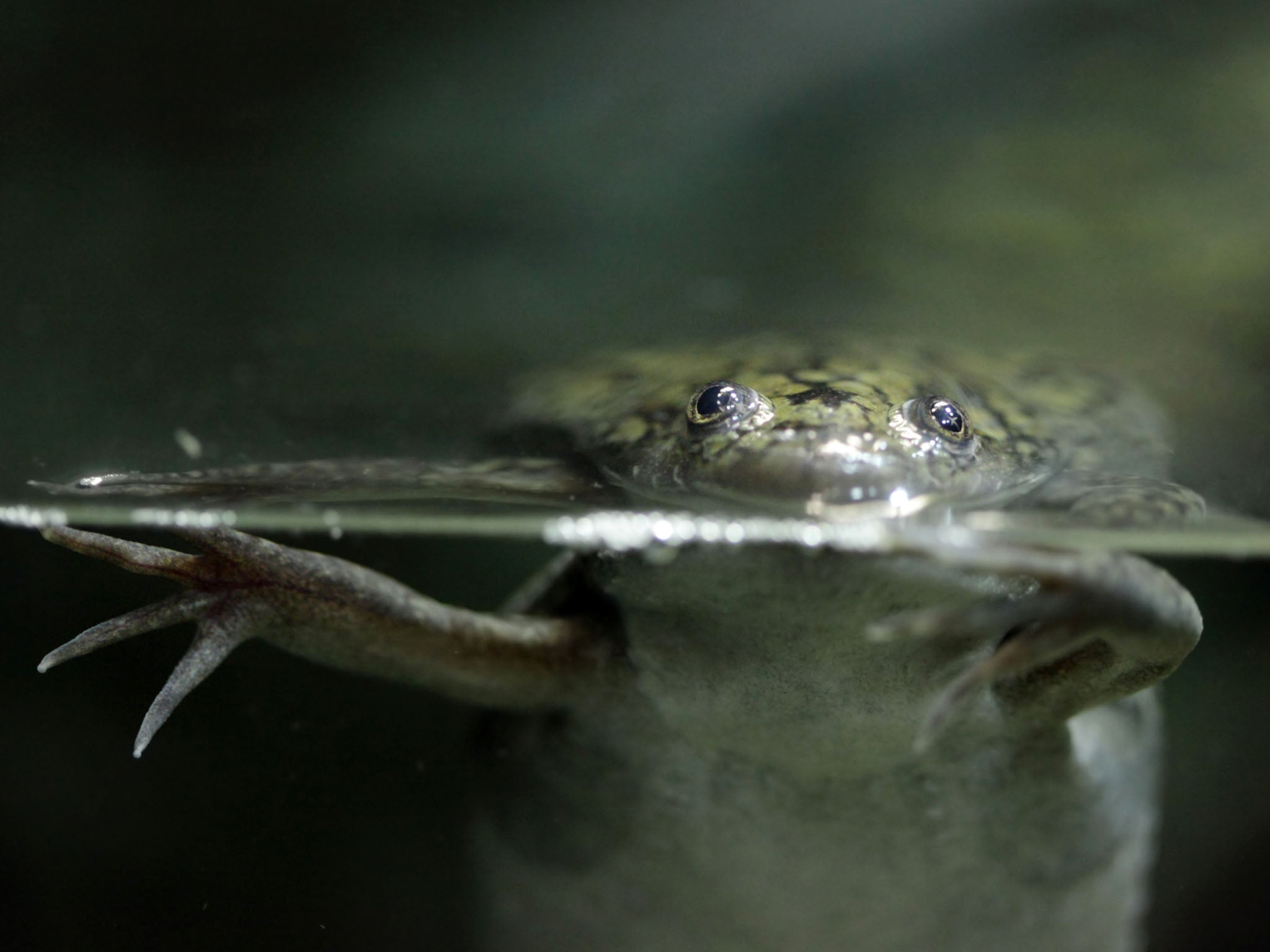

But scientists found they could induce the growth of a new leg after amputation on an African clawed frog by attaching a device they call a BioDome to the wound.

The BioDome, a silicon cap, was lined with a gel composed of a cocktail of five drugs, each of which had a different role in interrupting the body's natural process of closing over the wound to instead spur regeneration.

The scientists said the BioDome created an environment similar to that of an anmiotic sack in which babies grow.

Some drugs blocked the production of collagen – which would lead to scarring – while others encouraged the growth of new nerve fibres, blood vessels and muscle.

After a 24-hour period of exposure to the drugs, a near fully-functional leg would grow in 18 months.

The new legs had a similar bone structure to normal and several "toes" grew from the end of them, albeit without bones inside.

Though the legs were not completely functional, frogs were able to use them to swim.

The scientists who conducted the study – from Tufts and Harvard universities – said the results suggest that other animals may have dormant regenerative capabilities that can be induced through BioDome treatment.

“We’ll be testing how this treatment could apply to mammals next,” said Michael Levin, corresponding author of the study, director of the Allen Discovery Centre at Tufts and member of the Wyss Institute at Harvard.

He said: “Covering the open wound with a liquid environment under the BioDome, with the right drug cocktail, could provide the necessary first signals to set the regenerative process in motion.

“It’s a strategy focused on triggering dormant, inherent anatomical patterning programs, not micromanaging complex growth, since adult animals still have the information needed to make their body structures.”

Previous work at Tufts found that a single drug, progesterone, could induce a level of regeneration by itself.

But the limbs regenerated through progesterone grew as a spike and were not functional.

The success of the frog leg experiment lay in the selection of the drugs used in the BioDome.

Nirosha Murugan, lead author of the study and research affiliate at the Allen Discovery Centre at Tufts, said: "It’s exciting to see that the drugs we selected were helping to create an almost complete limb.”

Many creatures can fully regrow at least some limbs. Most – like salamanders, starfish and crabs – live in aquatic environments.

Regrowth begins with the formation of a mass of stem cells called a blastema at the end of a stump, which gradually reconstructs the lost limb. A wound will be rapidly covered by skin cells after the injury to protect the reconstructing tissue underneath.

Humans have comparatively slight regenerative capabilities. They can close wounds with new tissue growth and their livers can grow back to full size after losing 50 per cent of tissue.

But loss of a large and structurally complex limb cannot be restored by any natural process of regeneration in humans or any other mammals.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks