Fragments of 'world's oldest known Koran' unlikely to pre-date Prophet Mohamed, says expert

Scholars have claimed that ancient artefact could potentially rewrite Islamic history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

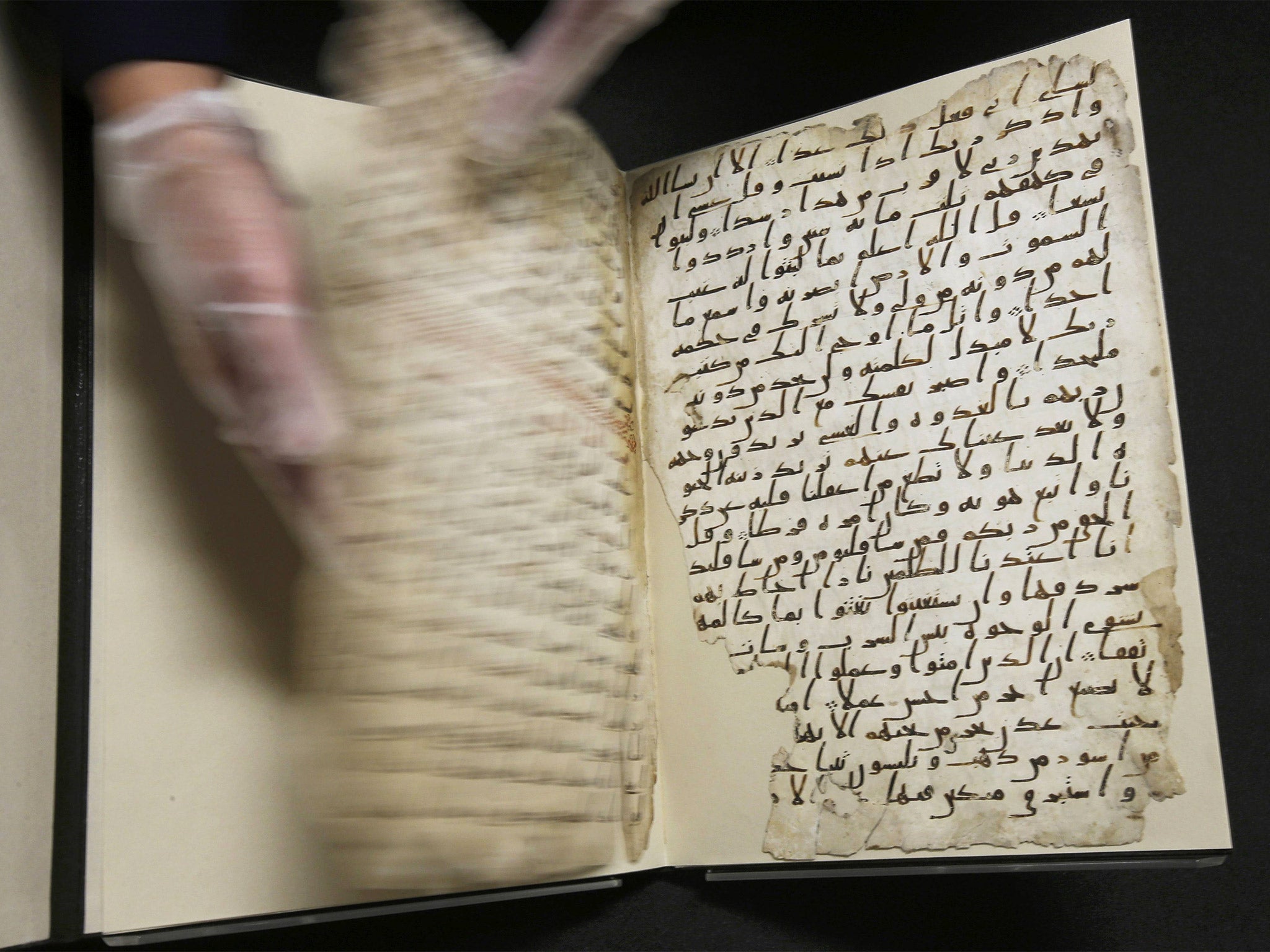

Your support makes all the difference.A manuscript of the Koran found buried away in a Birmingham library is more likely than not the oldest known direct record of the Prophet Mohamed's teachings, according to an expert at the university where it was discovered.

Amid claims the fragments could throw the traditional view of the origins of Islam into question, a member of the team involved in the discovery said further analysis of the ancient artefact threw up a "problem" with this theory.

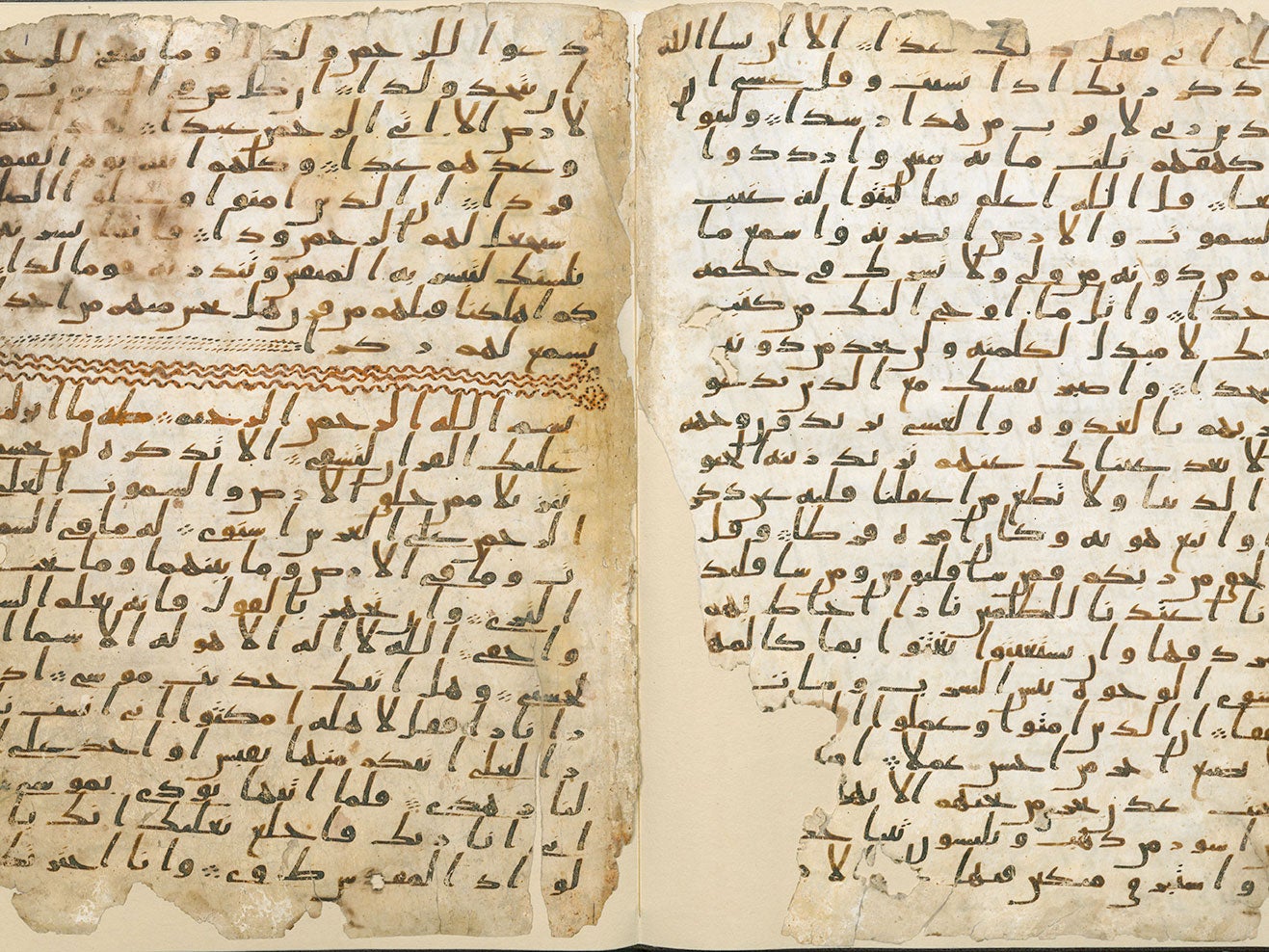

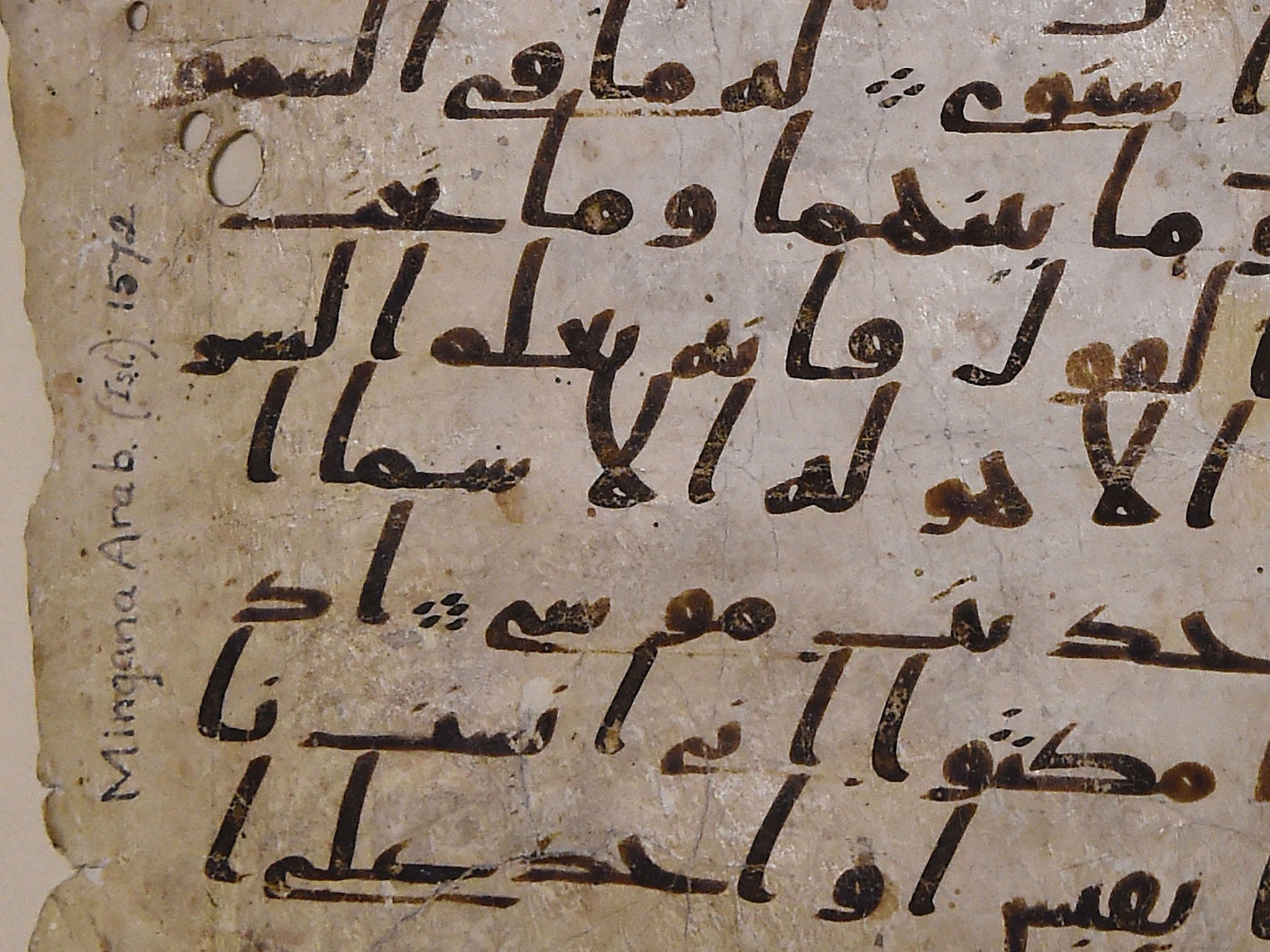

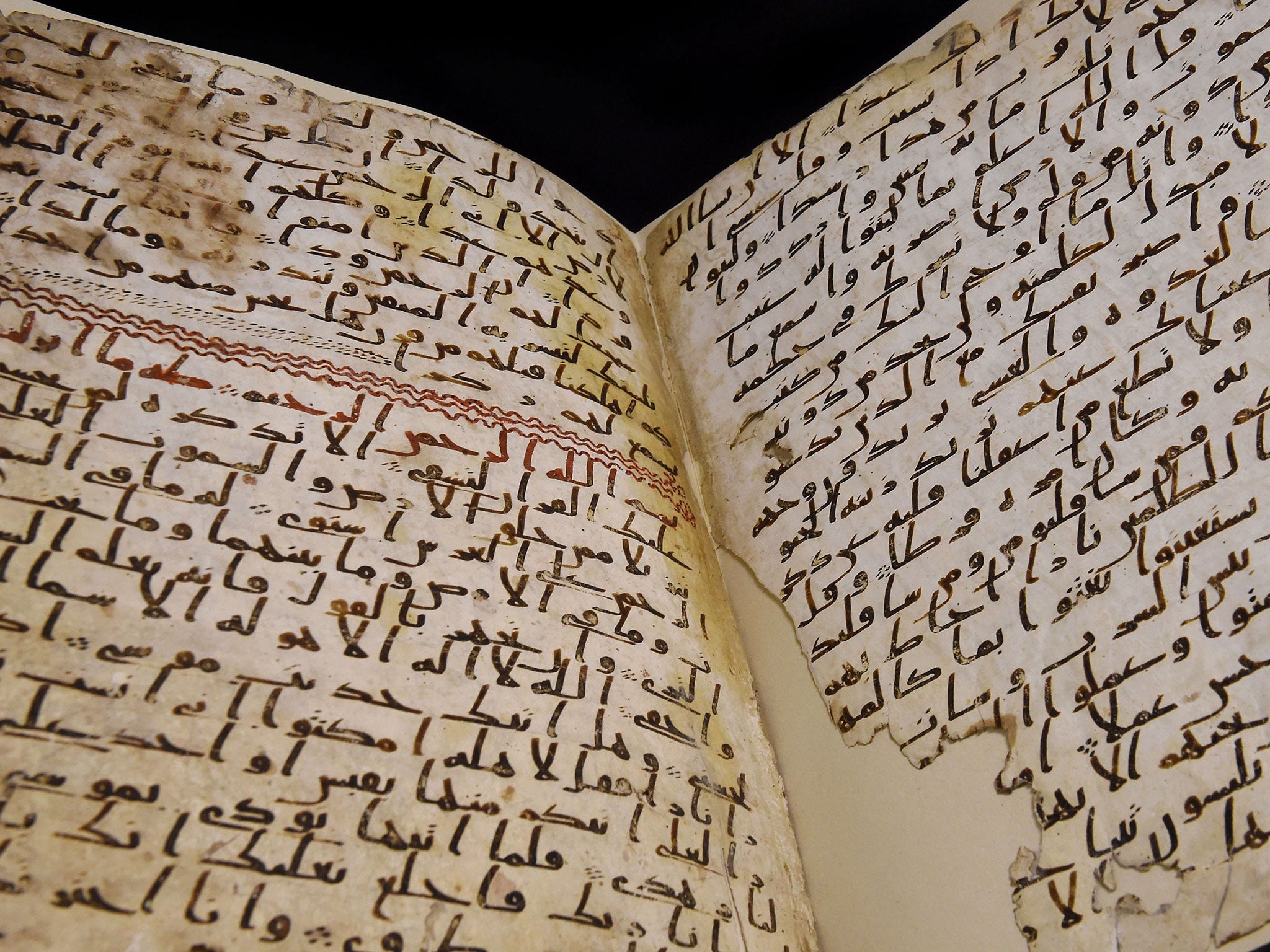

Carbon dating revealed last month that the four delicate pages of script etched on animal skin were at least 1,370 years old, potentially making it the oldest partial copy of the Koran in the world.

Modern methods can only accurately provide a range of dates for the Birmingham manuscripts origins, however, opening up a controversial time window during which the pages could have been created.

Speaking to The Independent, Birmingham University’s Professor of Christianity and Islam, David Thomas, said the tests tell us the animal from which the parchment for the Koran was made was alive between 568 AD and 645 AD.

Given the significance of the work, he said, the animal was likely killed specifically for the purposes of making the manuscript – meaning this date is likely to be very close to the assembly of the book itself.

Traditional teachings about the origins of Islam state that the Prophet Mohamed was alive between the years 570 and 632, and that he received the revelations which make up the Koran from 610 until his death.

“If we were to take the early dating [as fact] then it overthrows Islamic history as it is understood,” Professor Thomas said.

“It would mean that the Koran existed substantially as it has been passed down before Mohamed – before the traditional date of the beginnings of his revelations, or maybe even before he was born.”

It is the theory which has been hinted at by historian Tom Holland, who told The Times the manuscript “destabilises, to put it mildly, the idea that we can know anything with certainty about how the Koran emerged”.

The University of Oxford’s Dr Keith Small said it “gives more ground to what have been peripheral views of the Koran’s genesis, like that Mohamed and his early followers used a text already in existence and shaped it to fit their own political and theological agenda”.

Yet Professor Thomas believes that the opposite is in fact more likely. He said there is a telling clue that suggests the Koran actually comes from the later part of the date range, and that it would therefore “seem to support a traditional view”.

“There is a big problem with that earlier date range,” he said.

“As it turns out, on one of the four surfaces of our fragments we have a chapter division, which would seem to suggest that what we have was once a fully-formed Koran, possibly as early as the sixth century.

“In the middle of the seventh century there was a great expansion out of Arabian peninsula, and while there were a number of factors involved it is often explained at least in part as a religious movement.

“If that is the case, why would there be such a time lapse between a religious text coming into being in say 570, and a movement 60 years later? It doesn’t add up.”

Professor Thomas said the concept of a Koran that predates Mohamed would require “a radical revision of Islamic history”, adding: “I think there are substantial obstacles in the way of that.”

It means the person who wrote the newly-found Koran fragments could have known Mohamed personally, Professor Thomas said, “and that really is quite a thought to conjure with”.

The Birmingham manuscript will go on ticket-only public display at the university for a month in October, and Professor Thomas is preparing a workshop with experts to go over the questions the artefact raises.

He said plans for further tests are being worked on, and in the meantime expects a “much more substantial conference” to be held at a later date.

Susan Worrall, the university’s director of special collections, said the carbon dating already “contributes significantly to our understanding of the earliest written copies of the Koran”.

She said: “We are thrilled that such an important historical document is here in Birmingham, the most culturally diverse city in the UK.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments