The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Fossil footprints in Tanzania shed light on the first instances when early humans began walking upright

Scientists previously thought some of the footprints were made by a young bear walking upright

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A set of fossil footprints in Tanzania, previously thought to have been made by a bear, have now been found to be one of the oldest examples of upright walking in early humans.

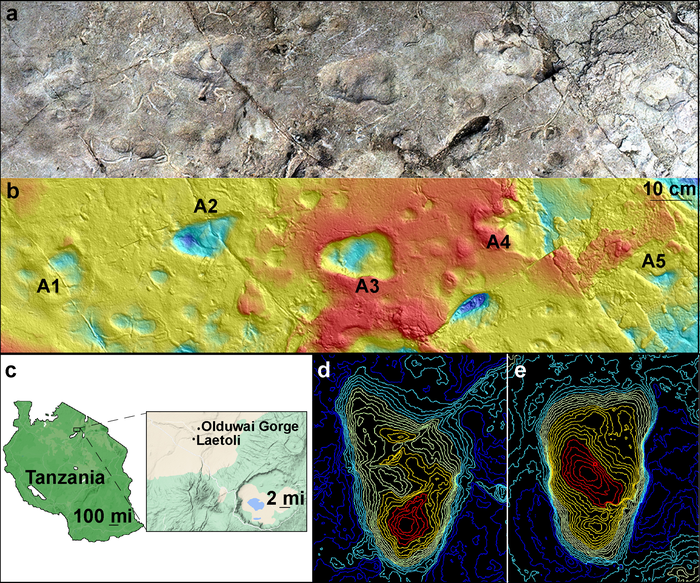

The site in Tanzania, where five consecutive footprints known as “The Laetoli Footprints” were discovered in 1970, was dated in previous studies to more than three million years ago.

While earlier research found that some of these fossil footprints were made by a human ancestor hominin species walking upright on two legs about 3.6 million years ago, the other marks in nearby sites fell into obscurity as a few resembled bear prints.

Some experts thought these were made by a young bear walking upright on its hind legs.

The current study, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, reveals that while these footprints in Site A are very different from those discovered in 1970, they were also made by an early upright walking-human – a bipedal hominin – suggesting that multiple species of hominins coexisted on the landscape.

“Given the increasing evidence for locomotor and species diversity in the hominin fossil record over the past 30 years, these unusual prints deserved another look,” Ellison McNutt, a co-author of the study from Ohio University, said in a statement.

In the new study, the scientists re-excavated and fully cleaned the five consecutive footprints at Site A and compared some of the tracks to the footprints of black bears, chimpanzees, and modern humans.

After assessing nearly 50 hours of footage of four semi-wild juvenile black bears at a rescue and rehabilitation centre in New Hampshire, the scientists found that they walked on two legs less than 1 per cent of the time, making it unlikely for a bear to have made the Laetoli footprints.

The scientists say this could be so given there were no ancient bear footprints of this time in the area walking on four legs.

“As bears walk, they take very wide steps, wobbling back and forth,” study senior author Jeremy DeSilva from Dartmouth College said in a statement.

“They are unable to walk with a gait similar to that of the Site A footprints, as their hip musculature and knee shape does not permit that kind of motion and balance,” Dr DeSilva added.

The researchers also measured, photographed, and 3D-scanned the footprints and found that these were indeed made by an early human hominin ancestor, including a large impression for the heel and the big toe.

While bear heels taper and their toes and feet are fan-like, early human feet are squared off and have a prominent big toe, the study noted.

However, the contentious footprints in Site A also record one leg over the other while walking – a gait called “cross-stepping,” which the scientists say may not have been produced by chimps – another animal in question.

“Cross-stepping is improbable, and perhaps impossible, when bears or chimpanzees walk bipedally,” the scientists wrote in the study.

“Although humans don’t typically cross-step, this motion can occur when one is trying to reestablish their balance,” says Dr McNutt explained.

Based on these new clues, the researchers believe the Site A footprints may have been the result of a hominin walking across an area that was an unlevel surface.

Comparing the foot proportions, morphology, and possible gait unravelled at Site A with the footprints of other human ancestors like Australopithecus afarensis uncovered at nearby sites, the scientists say there were different hominin species walking bipedally on this landscape “but in different ways on different feet.”

However, they are unsure which species of early humans may have made the prints at Site A.

“We’ve had this evidence since the 1970s. It just took the rediscovery of these wonderful footprints and a more detailed analysis to get us here,” Dr DeSilva added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments