Scientists puzzled by asteroids that hit Earth 35 million years ago and seemingly left no climate impacts

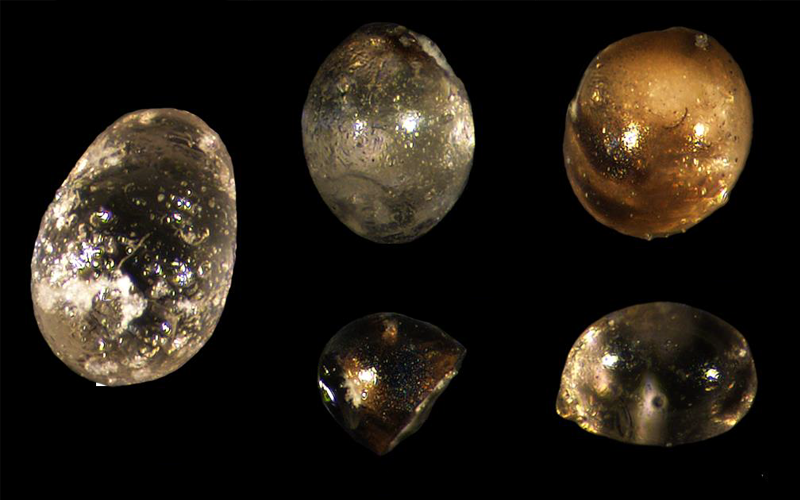

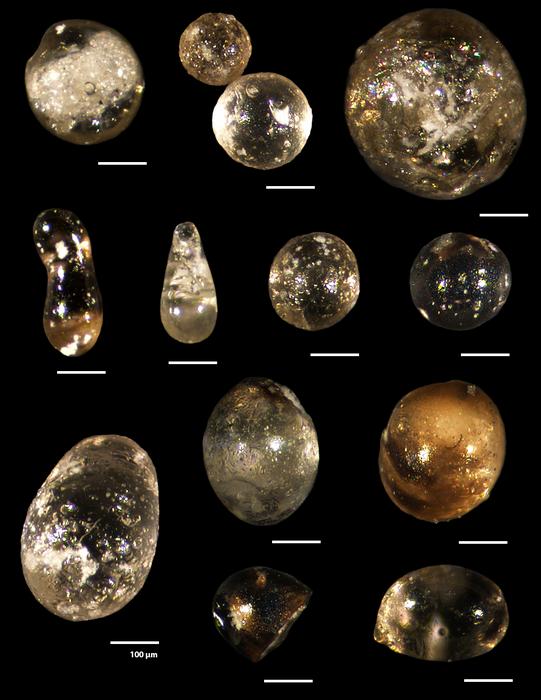

UK scientists used hundreds of tiny fossils that lived in the sea at the time to understand climate shifts tens of millions of years ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Researchers say they are surprised to discover that two massive asteroids that slammed into the Earth 35 million years ago caused no real climate impact.

After the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs hit what is now the Yucatan Peninsula more than 30 million years before these asteroids, its explosive energy resulted in irreversible climate change. It was those changes after the impact that likely caused the global mass extinction.

These asteroids, while smaller than the dinosaur killer, struck our planet about 25,000 years apart. They left miles-long craters in the Mid-Atlantic Chesapeake Bay and Siberia: the fourth- and fifth-largest asteroid craters on Earth.

But what happened after they hit is puzzling to scientists. They found no evidence of a lasting shift in climate some 150,000 years later.

“What is remarkable about our results is that there was no real change following the impacts. We expected the isotopes to shift in one direction or another, indicating warmer or cooler waters, but this did not happen,” University College London Professor Bridget Wade said. “These large asteroid impacts occurred and, over the long term, our planet seemed to carry on as usual.”

Isotopes are a type of atom, the smallest unit of matter that retains all the chemical properties of an element.

To determine the past climate, Wade and a team of researchers used analyzed isotopes in more than 1,500 fossils of tiny, shelled organisms that lived in the sea at the time known as foraminifera.

The fossils were between 35.5 to 35.9 million years old and were found in a nearly 10-foot-long rock core: a tube-like sample taken from underneath the Gulf of Mexico by the scientific Deep Sea Drilling Project. The pattern of the isotopes they looked at reflects how warm the waters were when the organisms were alive. They found shifts about 100,000 years before the asteroids hit, but none around the time of the impacts or afterwards.

They also uncovered evidence of the asteroid impacts in the form of thousands of tiny droplets of glass, or the compound silica. The droplets form after silica-containing rocks are vaporized by an asteroid. The silica ends up in the atmosphere but solidifies into droplets as it cools.

The work, which was funded by the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council, was published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

“However, our study would not have picked up shorter-term changes over tens or hundreds of years, as the samples were every 11,000 years,” said Wade. “Over a human time scale, these asteroid impacts would be a disaster. They would create a massive shockwave and tsunami, there would be widespread fires, and large amounts of dust would be sent into the air, blocking out sunlight.”

She noted that research into the Yucatan asteroid strike, also known as the Chicxulub impact crater, suggests a shift during less than a quarter of a century. And, previous investigations into the climate of the time have been inconclusive: some have linked impacts to cooling and others to warming.

But, the university argues, that using the foraminifera that lived at different ocean depths provides a more complete picture of the oceans’ response.

“Modeling studies of the larger Chicxulub impact, which killed off the dinosaurs, also suggest a shift in climate on a much smaller time scale of less than 25 years,” Wade said. “So we still need to know what is coming and fund missions to prevent future collisions.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments