Human DNA recovered from ‘lice glue’ on ancient mummies shed light on South American ancestry

New method may enable more samples to be analysed from human remains when bone and tooth remains are unavailable

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Human genetic material extracted from the “cement” used by head lice to glue their eggs to hairs thousands of years ago can provide important clues about ancient people and their migration patterns, a new study has revealed.

In a first, researchers, including those from the University of Reading in the UK, recovered human DNA from this cement-like substance on hairs taken from mummified remains that date back 1,500 to 2,000 years.

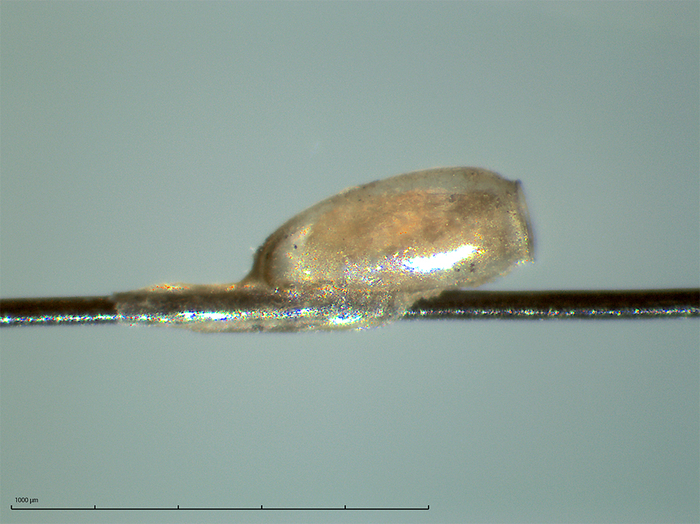

This cement is produced by female lice as they attach eggs — known as nits — to the hair, and in the process, some skin cells from the scalp also become encased in the glue-like substance, the scientists said.

“Like the fictional story of mosquitos encased in amber in the film Jurassic Park, carrying the DNA of the dinosaur host, we have shown that our genetic information can be preserved by the sticky substance produced by headlice on our hair,” Alejandra Perotti from the University of Reading, who led the research, said in a statement.

“In addition to genetics, lice biology can provide valuable clues about how people lived and died thousands of years ago,” Dr Perotti, Associate Professor in Invertebrate Biology, explained.

In the new study, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution on Tuesday, researchers extracted DNA from nit cement of specimens collected from a number of mummified remains of people who reached the Andes mountains of the San Juan province in central west Argentina some 1,500-2,000 years ago.

Scientists also studied ancient nits on human hair used in textile from Chile as well as nits from a shrunken head originating from the ancient Jivaroan people of Amazonian Ecuador.

Using the new method, researchers could find a genetic link between three of the mummies and humans in Amazonia 2,000 years ago, showing for the first time that the original population of the San Juan province migrated from the land and rainforests of the Amazon in the north of the continent.

“The genetic affinities deciphered from genome-wide analyses of this DNA inform that this population migrated from north-west Amazonia to the Andes of central-west Argentina,” the researchers wrote in the study.

They found that this new technique for recovering ancient human DNA offered better quality genetic material than that extracted through several other methods, offering new clues about pre-Columbian human migration patterns within South America.

Until now, archaeologists have extracted ancient DNA preferably from the dense bone from the skull or from inside teeth, as these provide the best quality samples.

However, skull and teeth remains are not always available, and it can also be unethical or against cultural beliefs to take samples from indigenous early remains.

In several cases, destructive sampling methods also cause severe damage to the specimens that can compromise scientific analysis.

Perotti and his team believe that recovering DNA from the cement delivered by lice could thus be a solution to the problem, especially since nits are commonly found on the hair and clothes of well-preserved and mummified humans.

Researchers say this new method can enable more samples to be studied from human remains in cases where bone and tooth samples are unavailable.

“Headlice have accompanied humans throughout their entire existence, so this new method could open the door to a goldmine of information about our ancestors, while preserving unique specimens,” Dr Perotti said.

Some of the nit samples used in the study contained the same concentration of DNA as a tooth, double that of bone remains, and four times that recovered from blood inside far more recent lice specimens, the scientists said.

In the DNA recovered from nit cement in one of the mummies, researchers also found the earliest direct evidence of Merkel cell Polymavirus, which they say on rare occasions could get into the body and cause skin cancer.

They believe the new method could reveal clues about the conditions in which a person lived and also provide hints to possible ancient viral diseases.

“The high amount of DNA yield from these nit cements really came as a surprise to us and it was striking to me that such small amounts could still give us all this information about who these people were, and how the lice related to other lice species but also giving us hints to possible viral diseases,” the study’s first author Mikkel Winther Pedersen from the University of Copenhagen said in a statement.

“There is a hunt out for alternative sources of ancient human DNA and nit cement might be one of those alternatives. I believe that future studies are needed before we really unravel this potential.” Dr Pedersen added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments