Dark matter: We know less about the universe's mysterious substance than we thought, scientists find

There's far more of the elusive dark matter than the regular matter we see around us

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dark matter is even more mysterious than we thought, according to new research.

The elusive matter makes up far more of the universe than the stuff we see around us. But it still remains almost entirely mysterious: we only know it exists through its interactions with the visible universe, and know very little about it.

Scientists have now revealed that a previous breakthrough – which at the time appeared that it could cast some light on dark matter – might actually have been wrong. Three years ago researchers were excited to find that a galaxy in a cluster of galaxies appeared to have become separated from the dark matter that surrounded it.

This discovery seemed to suggest that the dark matter was interacting with other dark matter through strange forces, not accounted for by gravity.

But new data shows that the dark matter did not actually separate from its galaxy at all.

Around 27 per cent of the universe is dark matter, which cannot be seen, while normal matter such as planets and stars makes up about 5 per cent.

Relatively little is known about the substance but scientists say galaxies like the Milky Way exist inside clumps of dark matter and would be unable to stay intact without the effect of its extra gravity.

Lead author Dr Richard Massey, from Durham University’s Centre for Extragalactic Astronomy, said: “The search for dark matter is frustrating, but that’s science.

“Meanwhile the hunt goes on for dark matter to reveal its nature.

“So long as dark matter doesn’t interact with the universe around it, we are having a hard time working out what it is.”

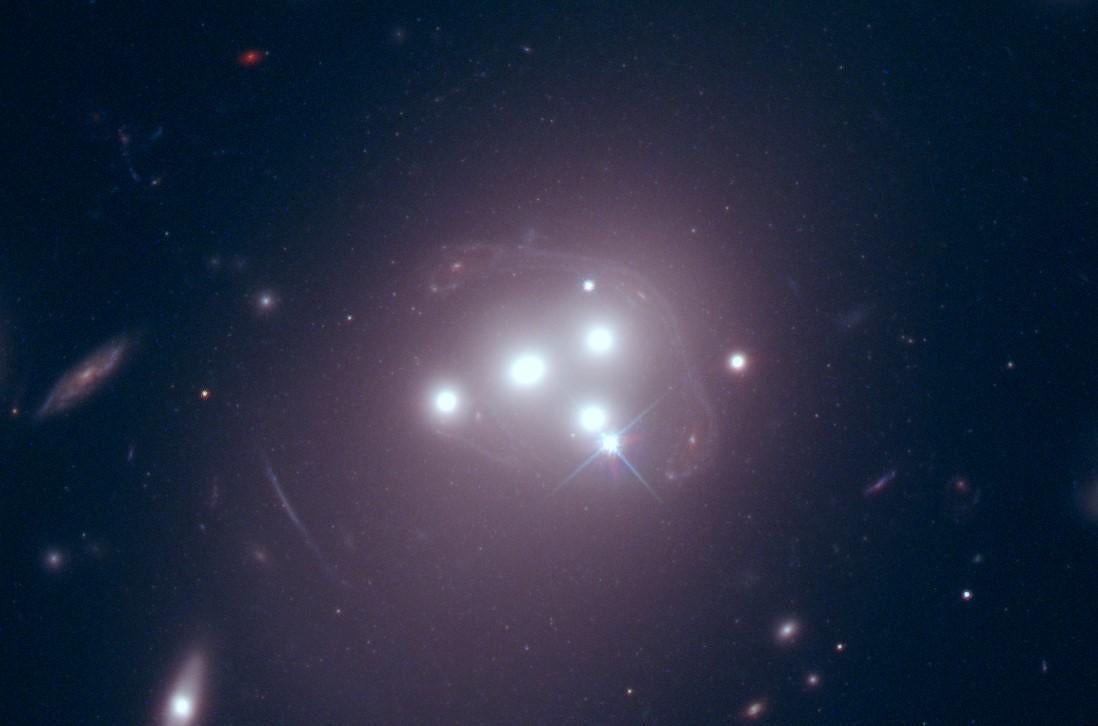

The apparent breakthrough was announced in 2015 following observations of a galaxy in the Abell 3827 cluster, approximately 1.3 billion light years from Earth, using the Hubble Space Telescope.

Until this point, dark matter had only been shown to interact with gravity.

The latest observations of the cluster were made using the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (Alma) in Chile, South America.

Alma picked up distorted infrared light from an unrelated background galaxy, which provided a higher resolution view and revealed the location of dark matter unidentified in the earlier study.

While the results show the dark matter stayed with its galaxy, the researchers said it did not necessarily mean the substance does not interact with forces other than gravity.

Dark matter could be interacting very little or this particular galaxy might be moving towards us, meaning we would not expect to see the substance displaced sideways, the team said.

The research will be presented at the European Week of Astronomy and Space Science meeting in Liverpool on Friday and published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments