Controversial study in which volunteers infected with Covid delivers first results

Research shows that average time from first exposure to viral detection and early symptoms was 42 hours, significantly shorter than existing estimates

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A controversial study in which participants were willingly infected with Covid has shown that it typically takes two days for symptoms to start developing after exposure to the virus.

The Human Challenge Programme found that an infection first appears in the throat and peaks after five days, at which point the virus is more abundant in the norse than the upper respiratory tract.

For the research, 36 healthy and young participants with no immunity to Covid were exposed to a low dose of the virus and then closely monitored by medics in a controlled environment for 24 hours a day over a two-week period.

Out of the volunteers, 18 became infected – 16 of whom developed mild-to-moderate symptoms, such as a running nose, sore throat, muscle aches and fever. None of the participants experienced serious symptoms.

Thirteen infected volunteers reported a temporary loss of smell, but this returned to normal within 90 days in all but three participants – the remainder continue to show improvement after three months. All volunteers are to be followed up for one year.

The research, led by a team at Imperial College London and funded by the government, also demonstrated that lateral flow tests are a reliable indicator of whether an individual had Covid.

However, it showed that the tests are less effective in detecting smaller viral loads in people at the very start and end of an infection.

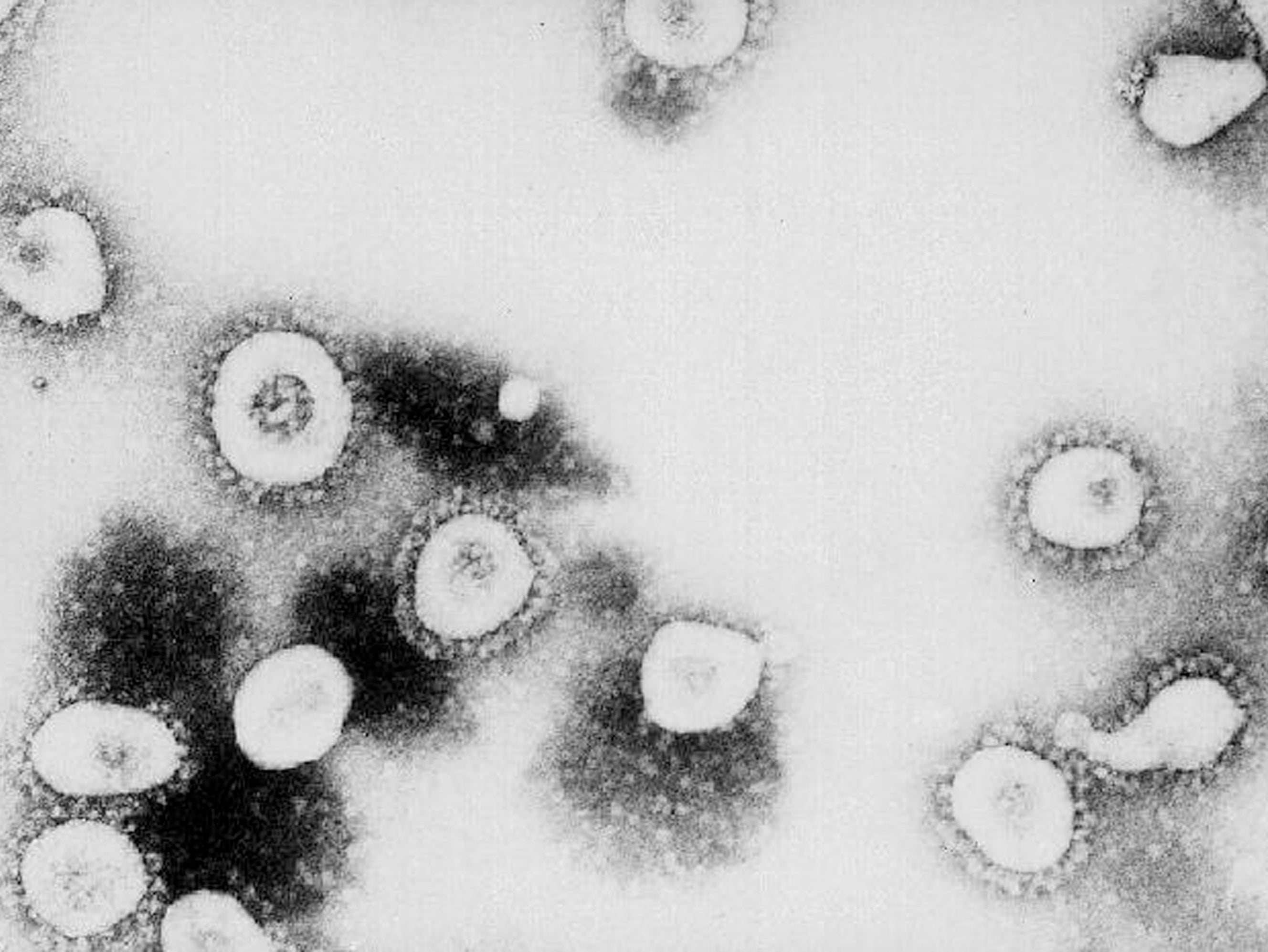

Participants were infected with a pre-Alpha variant of Sars-CoV-2 that was obtained in early 2020 from a hospitalised Covid patient, the researchers said.

Professor Sir Jonathan Van-Tam, England’s outgoing deputy chief medical officer, said the “invaluable” findings of the study will enable policymakers to “fine-tune our response” to Covid-19.

Among the 18 infected participants, the average time from first exposure to viral detection and early symptoms was 42 hours, significantly shorter than existing estimates, which put the average incubation period at five to six days.

In those who were infected, symptoms and the abundance of virus in the nose peaked at similar times, the researchers said.

Although participants were exposed to a “very small” amount of Sars-CoV-2, those who were infected still went on to develop high viral loads – even the asymptomatic.

This helps to “explain how the pandemic spread so quickly,” said Professor Christopher Chiu, chief investigator on the trial.

Although virus levels in the infected peaked around five days, lab tests were still able to detect lingering Sars-CoV-2 particles nine days into an infection, and up to a maximum of 12 days for some.

The team insisted many of the findings and conclusions from the study, which has yet to be peer-reviewed, will be applicable to different coronavirus variants.

“While there are differences in transmissibility due to the emergence of variants, such as Delta and Omicron, fundamentally, this is the same disease and the same factors will be responsible for protection against it,” said Prof Chiu.

It’s hoped the research will feed into the development of future antivirals, vaccines and diagnostic tests.

Professor Peter Openshaw, a co-investigator on the study, said the results would help to “accelerate” our understanding of “important questions like what’s going on in that period after the virus is put into the nose and what is the negotiation that’s getting on between the virus and the nasal lining”.

The scientists acknowledged the study was complex and controversial at times, with a clear framework of ethical and practical considerations in place to guide the research.

“The highest priority for us was making sure that participants were well taken care of and had no risk of going on to more severe Covid-19,” said Prof Chiu.

Given the high prevalence of immunity in the population, it will be near impossible to find people who have not developed some form of antibody response to Covid, whether through injection or infection, meaning the scientists cannot repeat the same study.

However, plans are in place to adapt the human challenge model – studies in which participants are infected with a pathogen to examine the response – and expose vaccinated volunteers to Covid in order to analyse breakthrough infections.

The researchers are also continuing to assess their current dataset and understand why half of the study participants “resisted infection”. Some of these individuals did show brief spikes in viral detection, before they rapidly disappeared.

This “gives us a clue” that suggests there is an active immune response going on which quickly removes the virus and prevents it from evolving into a detectable infection, Prof Chiu said.

“We are undertaking very detailed immunological analyses of both infected and the uninfected to try and understand why these people didn’t get infected and the potential immune mechanisms for suppressing infection.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments