Herd immunity ‘not a possibility’ as falling infections and hospitalisations appear to stall

Likely to be some ‘bumpiness’ in transmission and ‘uncertainty of what happens next over the next six months,’ says Professor Sir Andrew Pollard

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Herd immunity is “not a possibility” due to the prevalence of the Delta variant, a scientist behind the Oxford vaccine has warned, amid signs that the UK’s recent fall in Covid cases and hospital admissions is stagnating.

Professor Sir Andrew Pollard, director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, said there is likely to be some “bumpiness” in transmission and “uncertainty of what happens next over the next six months”, with scientists expecting a rise in cases ahead of winter as the weather worsens and people spend more time inside.

And because of mounting evidence that the highly transmissible Delta variant can infect those who have been vaccinated, it’s unlikely that herd immunity will ever be reached, said Sir Andrew, meaning infections will continue to bubble away throughout the population – as now appears to be the case.

Britain’s seven-day total up to 10 August is 7.3 per cent higher than it was for the previous week, while the current national rate stands at 277.4 infections per 100,000 people.

Following an unexpected and sudden drop in cases, which began around mid-July, cases bottomed out at 20,106 on 31 July, before briefly rising, falling, and then levelling out. A total of 23, 510 infections were recorded on Tuesday.

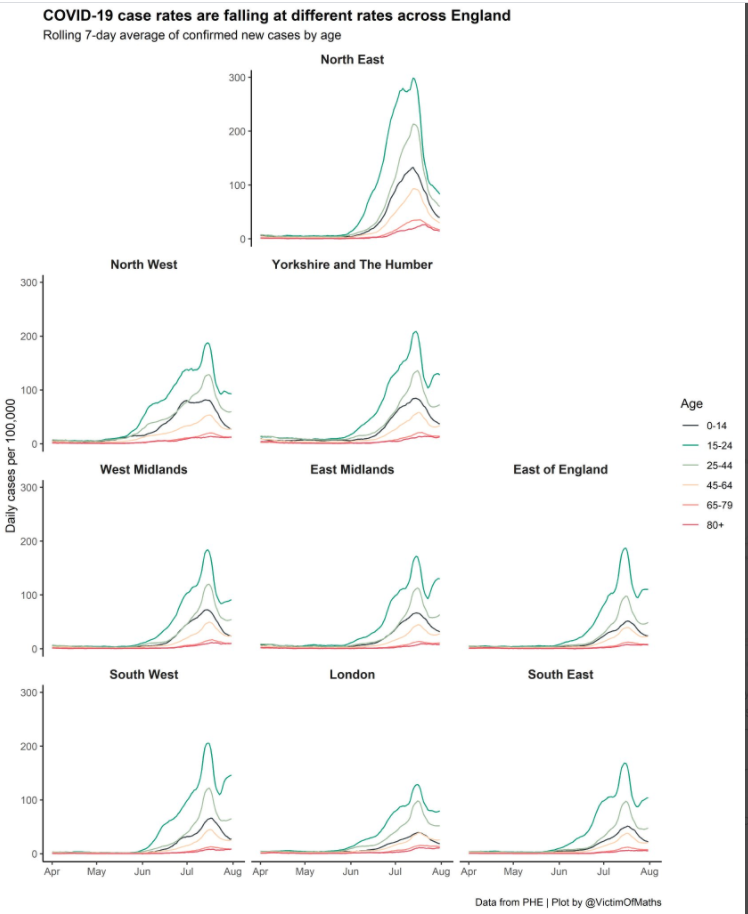

In England, this trend has largely been driven among the young across all regions of the country, except the North East, where rates are continuing to clearly fall in every age group.

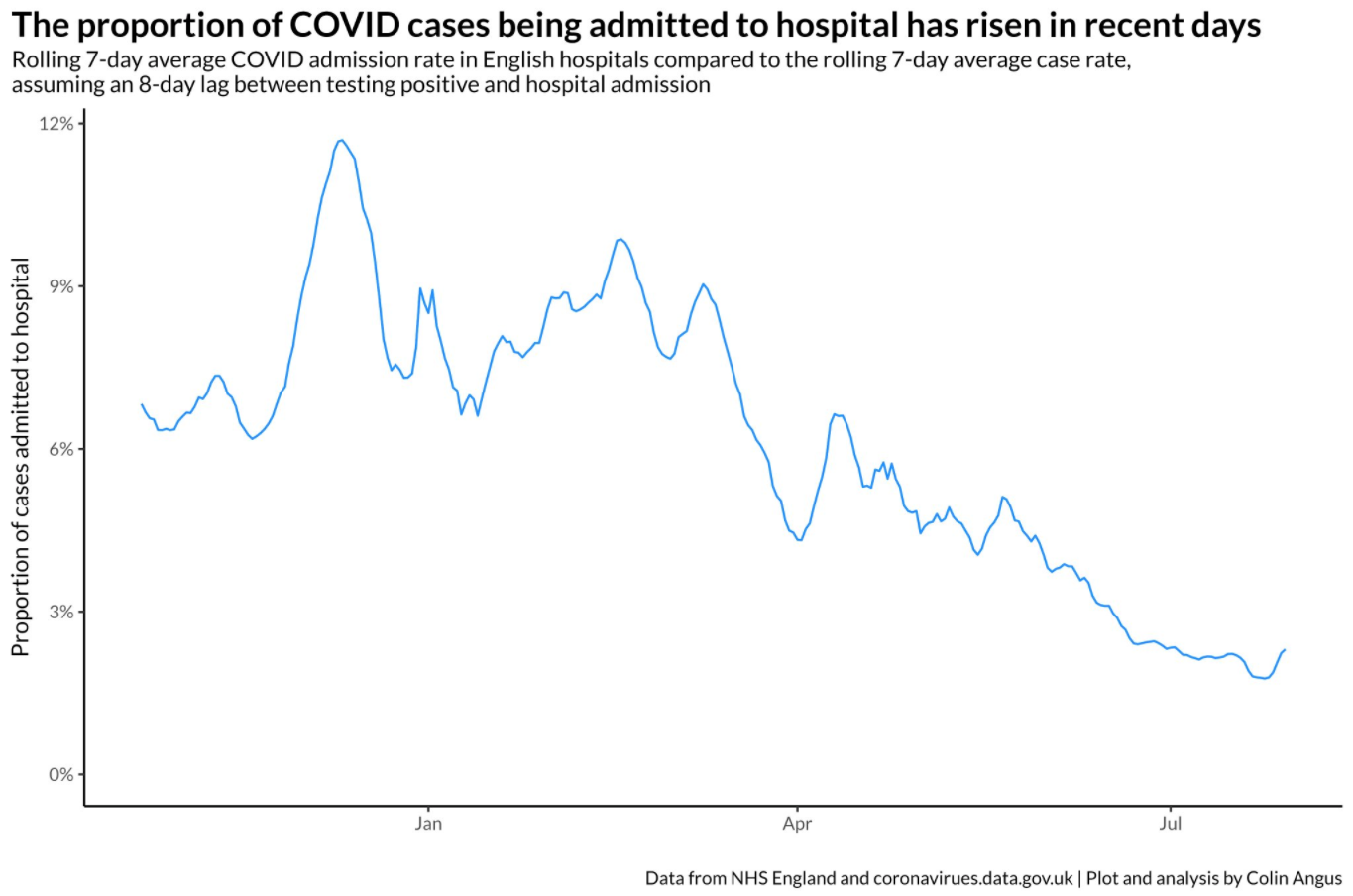

The case-to-hospitalisation ratio has also increased in recent weeks – albeit well below pre-vaccine levels. According to analysis up to 8 August, the proportion of cases that end up in hospital is up by 50 per cent on the week before.

Colin Angus, a senior research fellow and health inequalities modeller at the University of Sheffield, said this upturn is “entirely down” to the age mix of infections, with case rates rising among older adults once again.

“Prior to the latest stalling in the fall in cases, cases in younger age groups fell the most, so the percentage of cases coming from older age groups increased,” he said.

“As older cases are more likely to end up in hospital, this means the average proportion of cases that are hospitalised rises when cases get older. So it isn’t because people who test positive are getting Covid more severely.”

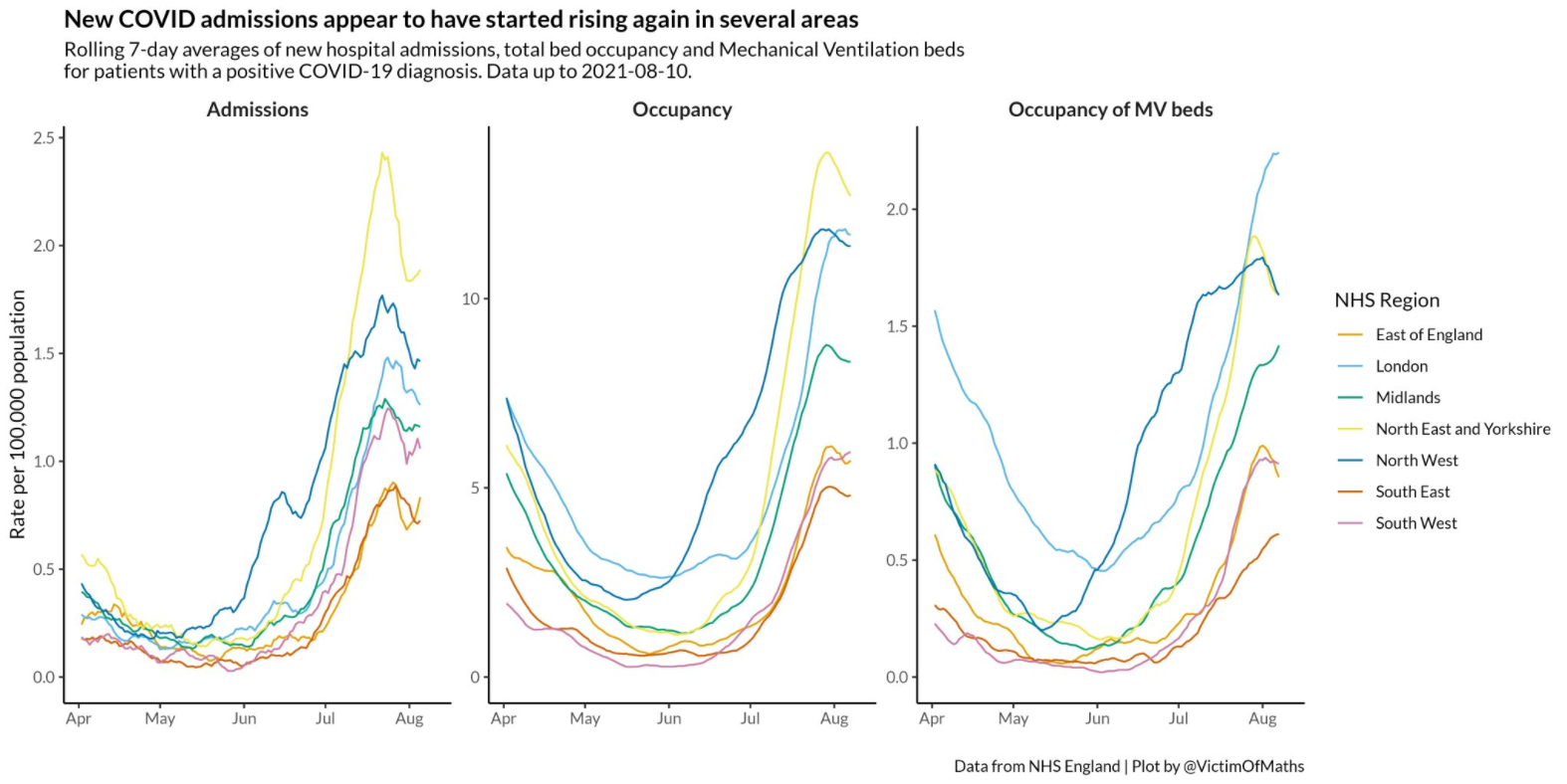

However, he warned that admissions are “definitely going back up in several regions, including across the north of England – an early signal that things might be heading back in the wrong direction”.

NHS data meanwhile show that Covid bed occupancy in hospitals appears to be flattening in all regions of England, with the highest rates seen in London and the northeast. Although this is again at a much lower level than recorded during the winter wave, it comes at a time of intense pressure on health services, which are attempting to work through large patient care backlogs.

Professor Keith Neal, an epidemiologist at Nottingham University, said that it was “very difficult” to interpret the recent trends, but insisted that the vaccines are continuing to offer lasting protection against serious disease and hospitalisation.

“The vast majority of people who are ill are unvaccinated,” he said. “At the moment the percentage of people who die with Covid who are vaccinated is going to increase because more people are vaccinated, and those vaccinated initially are the most at risk.

“There’s a huge disproportion though between vaccinated and non-vaccinated people being admitted.”

Although the vaccines have blunted the impact of Covid-19, they cannot be used to build up herd immunity in the population – a concept that Sir Andrew referred to as “mythical”.

“We know very clearly with coronavirus that this current variant, the Delta variant, will still infect people who have been vaccinated and that does mean that anyone who’s still unvaccinated, at some point, will meet the virus,” he told the parliamentary All-Party Group on coronavirus.

Due to the fact that herd immunity is “not a possibility”, this is “even more of a reason not to be making a vaccine programme around” it, Sir Andrew added.

Prof Neal insisted that the high number of infections being recorded shows “we are not out of the woods” yet, and drew comparisons with influenza. “Covid could be around for several decades until we get an effective vaccine that eliminates spread. We live with flu. We’ll have to treat Covid like flu, which keeps coming back.”

Experts also expect another rise in cases once children return to school next month, which could help fuel a wider wave in infections throughout the UK.

Dr Peter English, a former chair of the BMA Public Health Medicine Committee, said: “We know that the virus circulates in young people and spread between children. I’m very concerned about what’s going to happen when schools go back and people start mixing indoors more again.”

The number of weekly Covid deaths in England and Wales has also climbed to its highest level since the end of March, according to the Office for National Statistics. Some 404 deaths were registered in the seven days to 30 July – a 24 per cent increase on the previous week.

This reflects the delayed impact of the ‘exit wave’, which began in the UK in May when the first round of restrictions were eased and infections surged.

The number of daily new cases has fallen since then but this is yet to be reflected in the data for deaths, due to the length of time between someone getting Covid-19, becoming seriously ill and then dying.

Three-quarters of adults in the UK have meanwhile received both doses of a Covid-19 vaccine, the government said on Tuesday, amounting to 39,688,566 people.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments