Once infected, how does coronavirus affect the body?

As the outbreak worsens, so has the spread of panic and misinformation. Pam Belluck talks to the experts to dispel any misconceptions about the virus once and for all

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As cases of coronavirus infection proliferate around the world and governments take extraordinary measures to limit the spread, there is still a lot of confusion about what exactly the virus does to people’s bodies.

The symptoms – fever, cough, shortness of breath – can signal any number of illnesses, from flu to strep to the common cold. Here is what medical experts and researchers have learned so far about the progression of the infection caused by this new strain of coronavirus – and what they still don’t know.

How does Covid-19 cause infection?

The virus is spread through droplets transmitted into the air from coughing or sneezing, which people nearby can take in through their nose, mouth or eyes. The viral particles in these droplets travel quickly to the back of your nasal passages and to the mucous membranes in the back of your throat, attaching to a particular receptor in cells, beginning there.

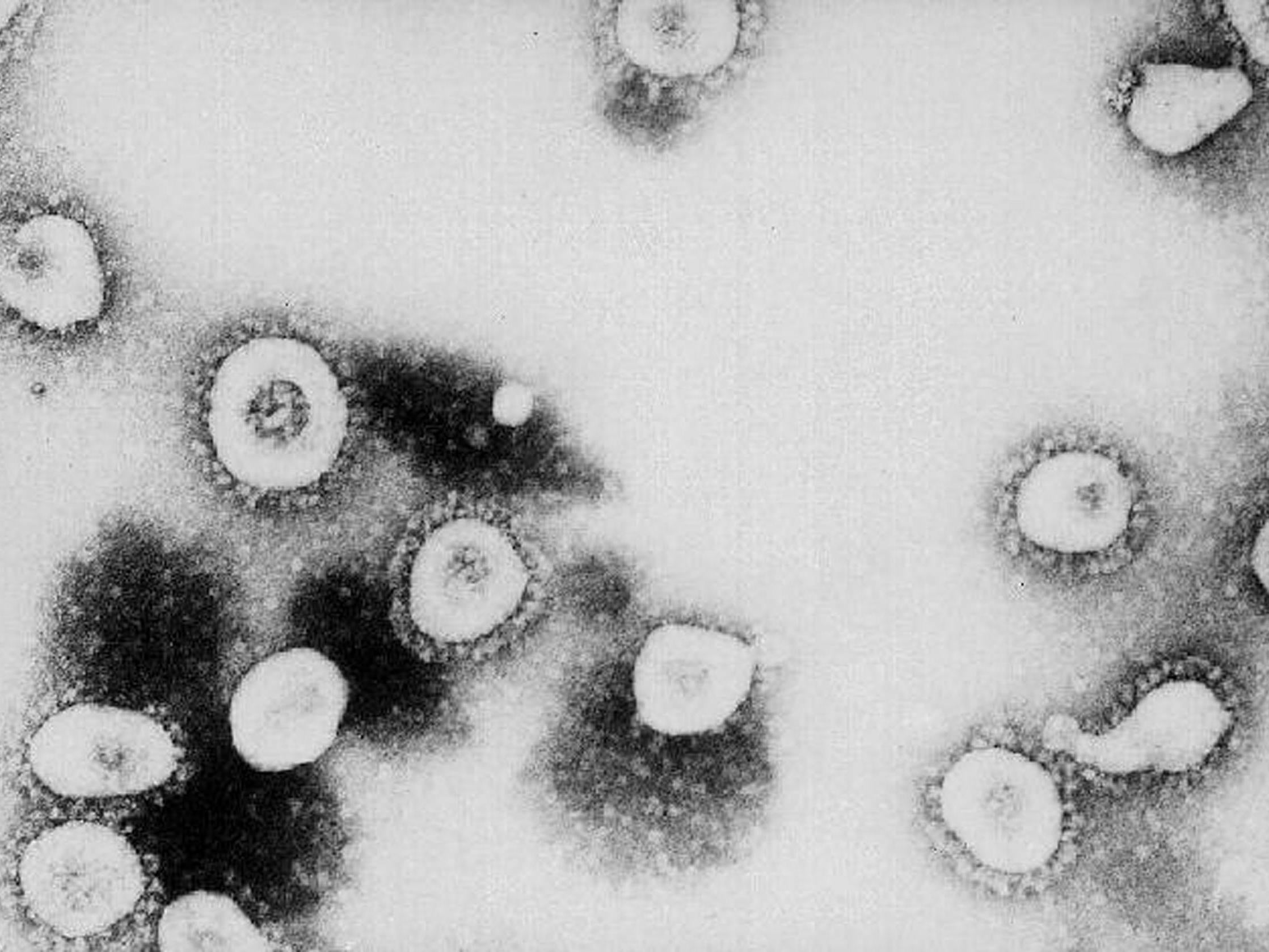

Coronavirus particles have spiked proteins sticking out from their surfaces, and these spikes hook onto cell membranes, allowing the virus’s genetic material to enter the human cell.

That genetic material proceeds to “hijack the metabolism of the cell and say, in effect, ‘Don’t do your usual job. Your job now is to help me multiply and make the virus’,” says Dr William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Centre in Nashville, Tennessee.

How does that process cause respiratory problems?

As copies of the virus multiply, they burst and infect neighbouring cells. The symptoms often start in the back of the throat with a sore throat and a dry cough.

80

The percentage of people who will get mild symptoms

The virus then “crawls progressively down the bronchial tubes”, Schaffner says. When the virus reaches the lungs, their mucous membranes become inflamed. That can damage the alveoli or lung sacs, and they have to work harder to carry out their function of supplying oxygen to the blood that circulates throughout our body and removing carbon dioxide from the blood so that it can be exhaled.

“If you get swelling there, it makes it that much more difficult for oxygen to swim across the mucous membrane,” says Dr Amy Compton-Phillips, the chief clinical officer for the Providence Health System, which included the hospital in Everett, Washington, that had the first reported case of the coronavirus in the US.

The swelling and the impaired flow of oxygen can cause those areas in the lungs to fill with fluid, pus and dead cells. Pneumonia, an infection in the lung, can occur.

Some people have so much trouble breathing, they need to be put on a ventilator. In the worst cases, known as Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), the lungs fill with so much fluid that no amount of breathing support can help, and the patient dies.

What trajectory does the virus take in the lungs?

Dr Shu-Yuan Xiao, a professor of pathology at the University of Chicago School of Medicine, has examined pathology reports on coronavirus patients in China. He says the virus appears to start in peripheral areas on both sides of the lung and can take a while to reach the upper respiratory tract, the trachea and other central airways.

Xiao, who also serves as the director of the Centre For Pathology and Molecular Diagnostics at Wuhan University, says that pattern helps explain why in Wuhan, where the outbreak began, many of the earliest cases were not identified immediately.

The infection can spread through the mucous membranes, from the nose down to the rectum

The initial testing regimen in many Chinese hospitals did not always detect infection in the peripheral lungs, so some people with symptoms were sent home without treatment.

“They’d either go to other hospitals to seek treatment or stay home and infect their family,” he says. “That’s one of the reasons there was such a wide spread.”

A recent study from a team led by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York found that more than half of 121 patients in China had normal CT scans early in their disease. That study and work by Xiao show that as the disease progresses, CT scans show “ground-glass opacities”, a kind of hazy veil in parts of the lung that are evident in many types of viral respiratory infections. Those opaque areas can scatter and thicken in places as the illness worsens, creating what radiologists call a “crazy paving” pattern on the scan.

Are the lungs the only part of the body affected?

Not necessarily. Compton-Phillips says the infection can spread through the mucous membranes, from the nose down to the rectum.

So while the virus appears to zero in on the lungs, it may also be able to infect cells in the gastrointestinal system, experts say. This may be why some patients have symptoms like diarrhea or indigestion. The virus can also get into the bloodstream, Schaffner says.

The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention says that RNA from the new coronavirus has been detected in blood and stool specimens, but that it’s unclear whether the infectious virus can persist in blood or stool.

Bone marrow and organs like the liver can become inflamed too, says Dr George Diaz, section leader for infectious diseases at Providence Regional Medical Centre in Everett, Washington, whose team treated the first US coronavirus patient. There may also be some inflammation in small blood vessels, as happened with Sars, the viral outbreak in 2002 and 2003.

Why do some people get very ill but most don’t?

About 80 per cent of people infected with the new coronavirus have relatively mild symptoms. But about 20 per cent of people become more seriously ill; and in about two per cent of patients in China, which has had the most cases, the disease has been fatal.

Experts say the effects appear to depend on how robust or weakened a person’s immune system is. Older people or those with underlying health issues, like diabetes or another chronic illness, are more likely to develop severe symptoms.

What do scientists still not know about coronavirus patients?

A lot. Although the illness resembles Sars in many respects and has elements in common with influenza and pneumonia, the course a patient’s coronavirus will take is not yet fully understood.

Some patients can remain stable for over a week and then suddenly develop pneumonia, Diaz says. Some patients seem to recover but then develop symptoms again.

Xiao says that some patients in China recovered but got sick again, apparently because they had damaged and vulnerable lung tissue that was subsequently attacked by bacteria in their body. Some of those patients ended up dying from a bacterial infection, not the virus. But that didn’t appear to cause the majority of deaths, he says.

Other cases have been tragic mysteries. Xiao says he personally knows a man and woman who got infected but seemed to be improving. Then the man deteriorated and was hospitalised.

“He was in ICU, getting oxygen, and he texted his wife that he was getting better, he had good appetite and so on,” Xiao says. “But then in the late afternoon, she stopped receiving texts from him. She didn’t know what was going on. And by 10pm, she got a notice from the hospital that he had passed.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments