Scientists discover the reason people believe in conspiracy theories

Mind-set of those with unusual beliefs about everything from 9/11 to moon landings linked with support for creationism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

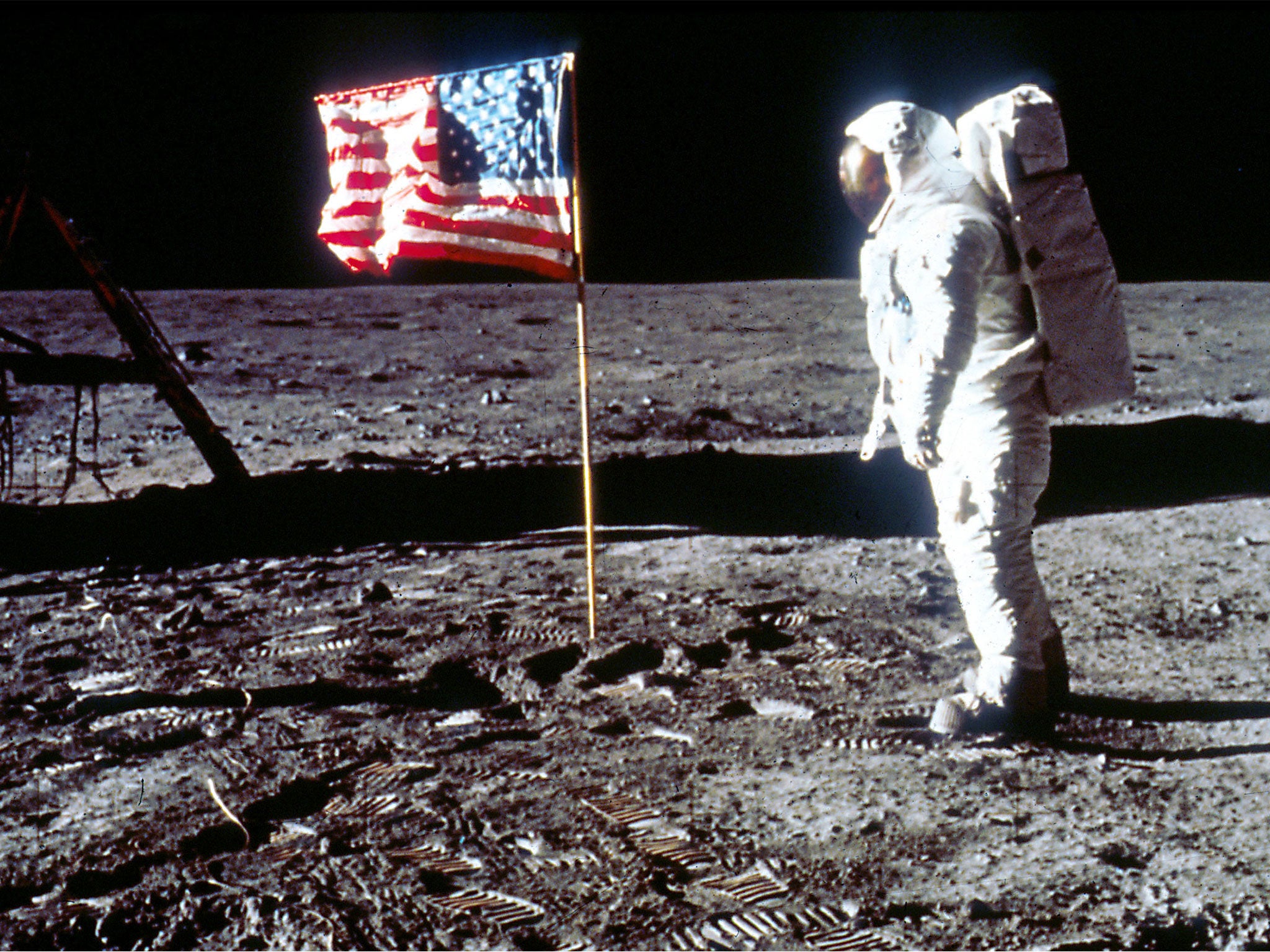

Your support makes all the difference.Psychologists have identified the mind-set that makes people believe in far-fetched ideas, from 9/11 conspiracy theories to staged moon landings.

Conspiracy theorists have entered the mainstream of late with the proliferation of “fake news” and the popularity of personalities like InfoWars host Alex Jones.

In an effort to improve education about their ideas, a team of French and Swiss scientists set out to investigate why certain people are predisposed to this way of thinking.

They found that conspiracy theorists are more likely to think “everything happens for a reason” and things are “meant to be”, an approach they share with another group often considered extreme in their beliefs: creationists.

“We find a previously unnoticed common thread between believing in creationism and believing in conspiracy theories,” said Dr Sebastian Dieguez of the University of Fribourg, one of the researchers behind the study.

“Although very different at first glance, both these belief systems are associated with a single and powerful cognitive bias named teleological thinking, which entails the perception of final causes and overriding purpose in naturally occurring events and entities.”

In practice, a teleological approach means someone will agree with statements such as “the sun rises in order to give us light” or “the purpose of bees is to ensure pollination”.

When children are just beginning to learn about their world around them, teleological thinking is a key part of their learning process.

The approach has long been rejected by scientists, but has proved highly resilient among much of the wider adult population regardless, particularly on the subject of evolution.

Having recognised the similarities between the creationist and “conspiracist” worldview, Dr Dieguez and his colleagues conducted a series of tests to interrogate how deep this connection went.

They began by surveying 150 college students in Switzerland, and found a correlation between a teleological approach and belief in conspiracies.

Next they used data from a much larger study of 1,250 people in France and found an association between belief in conspiracy theories and creationism.

Finally, they recruited a further 700 people and asked them to complete a new set of questionnaires that allowed them to probe the link between teleological thinking, creationism, and conspiracism more deeply.

“By drawing attention to the analogy between creationism and conspiracism, we hope to highlight one of the major flaws of conspiracy theories and therefore help people detect it, namely that they rely on teleological reasoning by ascribing a final cause and overriding purpose to world events,” said Dr Dieguez.

“We think the message that conspiracism is a type of creationism that deals with the social world can help clarify some of the most baffling features of our so-called ‘post-truth era.’”

The scientists, who published their findings in the journal Current Biology, want their work to inform science educators as well as policy makers who wish to discourage the endorsement of “socially debilitating and sometimes dangerous beliefs”.

The conspiracist mind-set, they say, can inform beliefs that have real world consequences – such as denial of global warming or rejection of vaccines for children.

Dr Dieguez and his colleagues are now using their work to assess current attempts to educate young people about conspiracy theories and other types of misinformation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments