Superbug resistant to 'antibiotic of last resort' found in US

'It basically shows us that the end of the road isn't very far away for antibiotics'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For the first time, researchers have found a person in the United States carrying a bacteria resistant to antibiotics of last resort, an alarming development that the top U.S. public health official says could mean "the end of the road" for antibiotics.

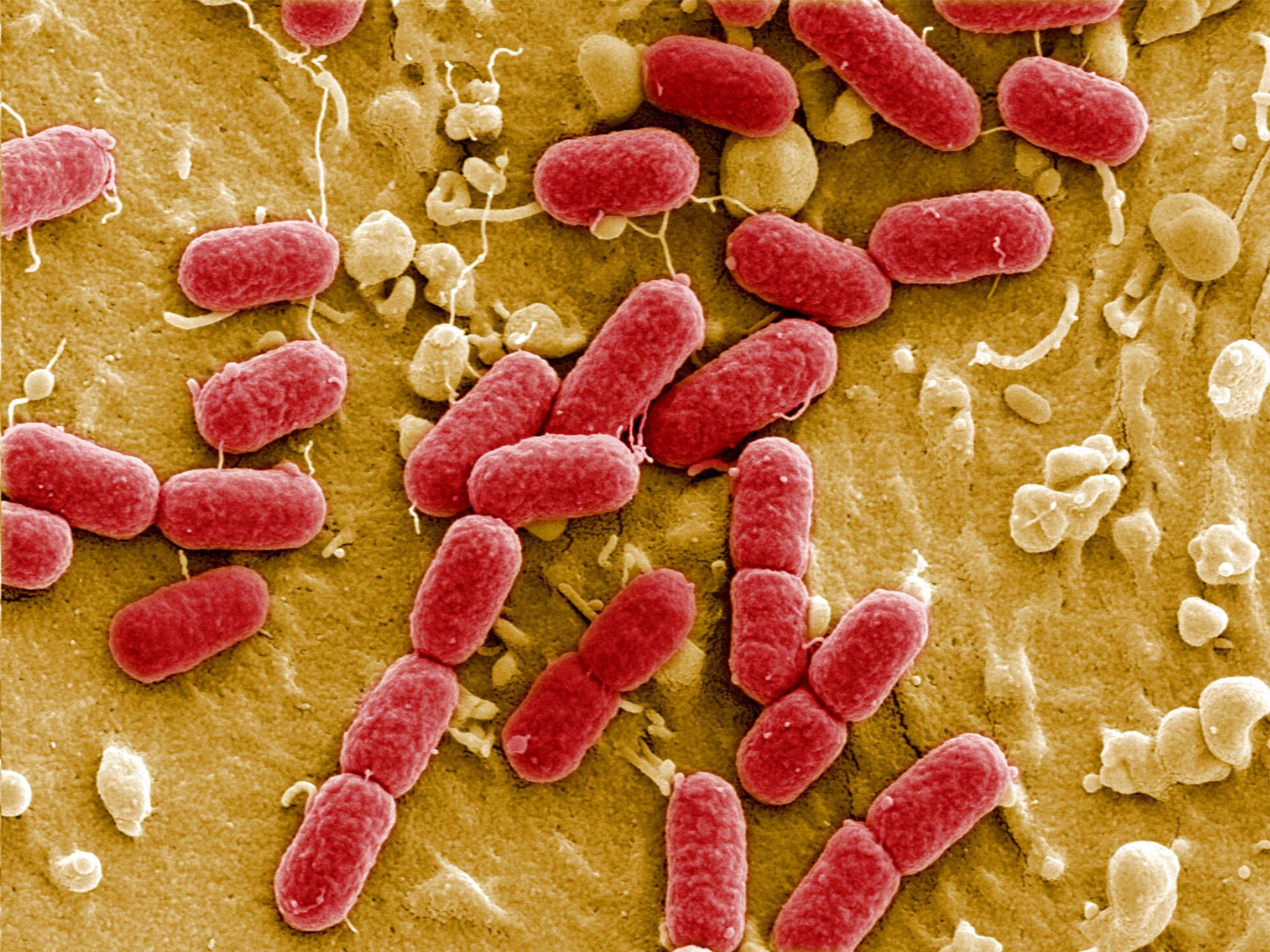

The antibiotic-resistant strain was found last month in the urine of a 49-year-old Pennsylvania woman. Department of Defense researchers determined that her infection involved a strain of E. coli resistant to the antibiotic colistin, according to a study published Thursday in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, a publication of the American Society for Microbiology. The authors wrote that the discovery "heralds the emergence of a truly pan-drug resistant bacteria."

Colistin is the antibiotic of last resort for particularly dangerous types of superbugs, including a family of bacteria known as CRE, which health officials have dubbed "nightmare bacteria." In some instances, these superbugs kill up to 50 percent of patients who become infected. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has called CRE among the country's most urgent public health threats.

It's the first time this colistin-resistant strain has been found in a person in the United States. Last November, public health officials around the globe reacted with alarm when Chinese and British researchers reported finding the colistin-resistant strain in pigs, raw pork meat and in a small number of people in China. The deadly strain was later discovered in Europe and elsewhere.

"It basically shows us that the end of the road isn't very far away for antibiotics -- that we may be in a situation where we have patients in our intensive-care units, or patients getting urinary tract infections for which we do not have antibiotics," CDC Director Tom Frieden in an interview Thursday.

"I've been there for TB patients. I've cared for patients for whom there are no drugs left. It is a feeling of such horror and helplessness," Frieden added. "This is not where we need to be."

CDC officials are working with Pennsylvania health authorities to interview the patient and family to identify how she may have contracted the bacteria, including reviewing recent hospitalizations and other healthcare exposures. CDC hopes to screen the patient and other contacts to see if others might be carrying the organism. Local and state health departments will also be collecting cultures as part of the investigation.

Scientists and public health officials have long warned that if the resistant bacteria continue to spread, it could seriously limit available treatment options. Routine operations could become deadly. Minor infections could become life-threatening crises. Pneumonia could be more and more difficult to treat.

Already, doctors had been forced to rely on colistin as a last-line defense against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The drug is hardly ideal. It is more than half a century old and can cause serious damage to a patient's kidneys. And yet, because doctors have run out of weapons to fight a growing number of infections that evade more modern antibiotics, it has become a critical tool in fighting off some of the most tenacious infections.

Bacteria develop antibiotic resistance in two ways. Many acquire mutations in their own genomes that allow them to withstand antibiotics, although that ability can't be shared with pathogens outside their own family.

Other bacteria rely on a shortcut: they get infected with something called a plasmid, a small piece of DNA, carrying a gene for antibiotic resistance. That makes resistance genes more dangerous because plasmids can make copies of themselves and transfer the genes they carry to other bugs within the same family as well as jump to other families of bacteria, which can then "catch" the resistance directly without having to develop it through evolution.

The colistin-resistant E. coli found in the Pennsylvania woman has this type of resistance gene.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments