How are cod evolving in response to overfishing?

Tom Cameron explains how ‘supergenes’ may have made cod become more resilient to environmental changes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cod “supergenes” have shed light on how they respond to overfishing, and these changes could make them more resilient to other environmental shifts – that’s according to a new study published by scientists in Norway. This could be good news, insofar that cod have genetic architecture in place that will permit them to respond to climate change, but for now it’s rather speculative.

For those of us who study how fish species evolve under strong selective pressure from commercial fishing, cod has been a poster species. For instance, scientists have previously found that cod in the north west Atlantic showed signs of reproducing at a smaller size or younger age before numbers collapsed.

The latest study examined the current and historical genome (the complete set of genetic instructions contained in an organism’s DNA) of cod. The scientists were particularly interested in areas of highly-conserved “supergenes” and what they can tell us about these ecologically critical but heavily exploited marine predators.

Supergenes are not extra individual genes as such. Rather, they are combinations of genetic material that are more conserved through the generations. Often they are strongly coupled or linked and are responsible for a set of traits in an organism that are very important, such as linking growth rates with reproduction capacity.

The authors found three supergenes conserved in the cod off of Norwegian shores. And the three supergenes were found in different relative abundance in two distinct cod populations: inshore and offshore. This reinforces what we know about cod in the north east Atlantic and is a good thing, since if the cod were all one breeding population they would be more vulnerable to overexploitation.

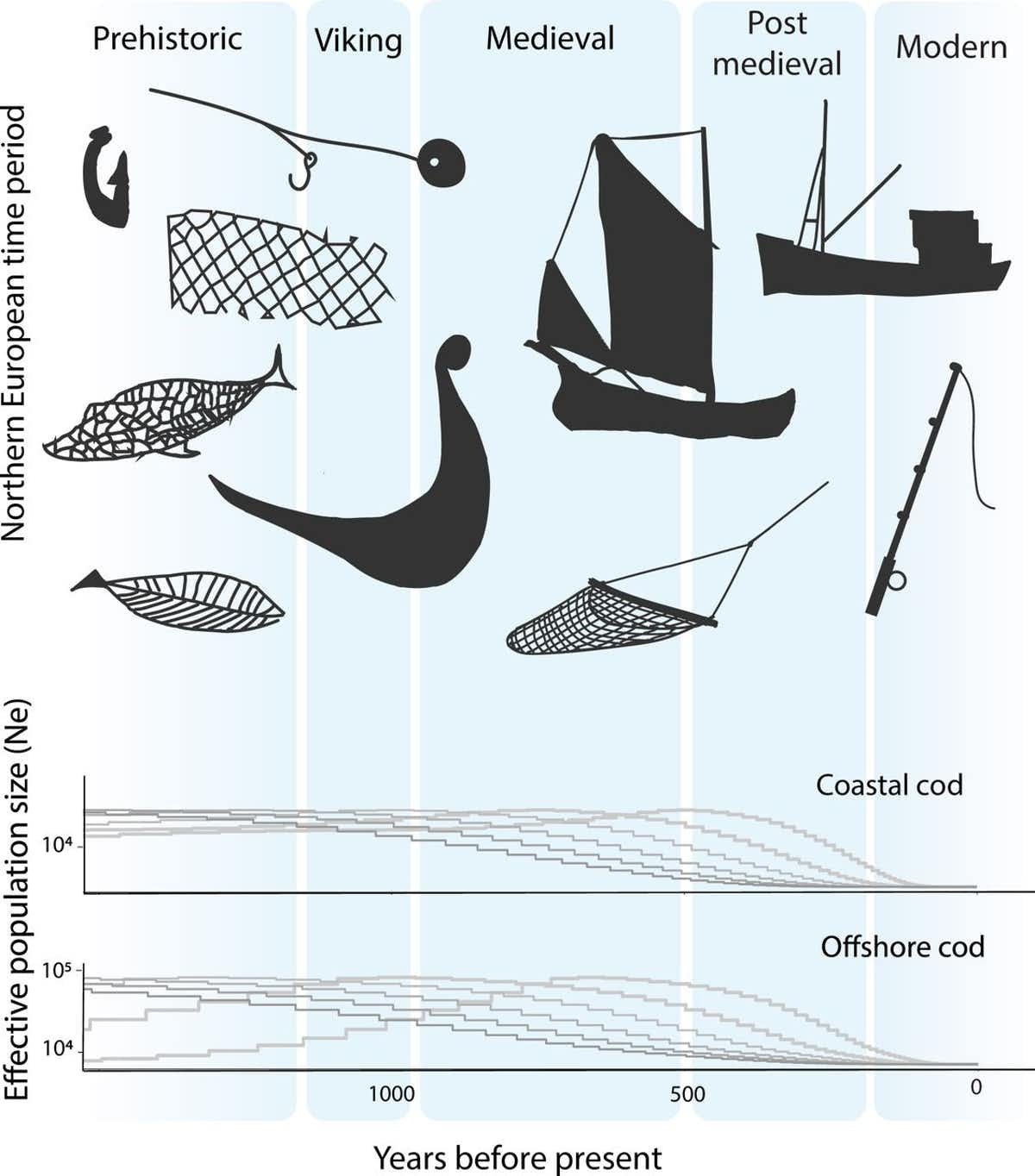

An interesting consequence of this research is that the scientists can combine their genomics approaches with knowledge from old stories and pictures, and records of fish bones and fishing equipment found at archeological sites, in order to reconstruct the likely population sizes of cod through history. Recent studies on several fish species have shown the true baseline of their abundance in seas around Europe is likely underappreciated. Indeed, this new analysis suggests the overexploitation of cod reduced their abundance many hundreds of years before modern commercial fishing began, and the signature of overexploitations is etched in their genome.

How human predators change their prey

Across lots of different species, it is now well recognised that populations are constantly changing, and this includes evolved changes to their body size, shape or traits like growth rate being observed in just a few generations with significant consequences for how population numbers fluctuate.

Scientists recently updated a large data set that now compiles more than 7,000 examples of contemporary changes to biological traits in wild populations. The researchers examined whether observed trait changes, such as a shift in average body size, were short-term and reversible, or whether they were more permanent evolved responses to some change in the local environment such as increasing temperature or an introduced predator.

Their data clearly showed that the largest and fastest rates of trait change were associated with predation, for example when a predator picks off the slowest, smallest, largest or least camouflaged individuals in a wild population, leading to directional change to being smaller, larger, or faster. These rates of change were especially fast when that predator was human.

Theories of human-caused, harvest-induced evolution are now well established. There are many good examples where selective harvest of fish and game species has caused long term change, for example by influencing behaviour, body shape or size and growth rates to sexual maturity. I have carried out laboratory-based research demonstrating both the probability that harvest-induced evolution can occur and the likely impact such permanent genetic change can have on things like population size or resulting yields.

This field of study is not without controversy, but it is now generally accepted that we should take evolutionary selection pressure into account when we utilise wild animals and plants for resources. As new scientific approaches and opportunities to examine the genome of wild animals emerge, we may find more supergenes and the stories they can tell us of how organisms respond to the world they live in.

Tom Cameron is a senior lecturer in ecology at the University of Essex. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments