Flying chariots and exotic birds: How 17th-century dreamers planned to reach the moon

We’ve only travelled into space in the past 100 years – but humanity’s desire to reach its closest neighbour is far from recent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People have been dreaming about space travel for hundreds of years, long before the arrival of the spectacular technologies behind space exploration today – mighty engines roaring fire and thunder; shiny metal shapes gliding in the vastness of the universe.

We’ve only travelled into space in the last century, but humanity’s desire to reach the moon is far from recent. In the second century AD, Lucian’s True History, a parody of travel tales, already pictured a group of adventure-seekers lifted to the moon. A whirlwind delivered them into the turbulence of lunar politics – a colonial war.

And much earlier than any beep of a satellite, these dreams of moon travel were given real, serious thought. The first technical reckoning of how to travel to the moon can be found in the 17th century.

This was inspired by astronomic discoveries. For a long time, it was thought that the world was encapsulated with ethereal or crystal spheres, in which nested celestial bodies. But then Galileo managed to compile enough observational data to support Copernicus’s theory of heliocentrism. This meant that for the first time, the moon began to be considered an opaque, Earth-like object.

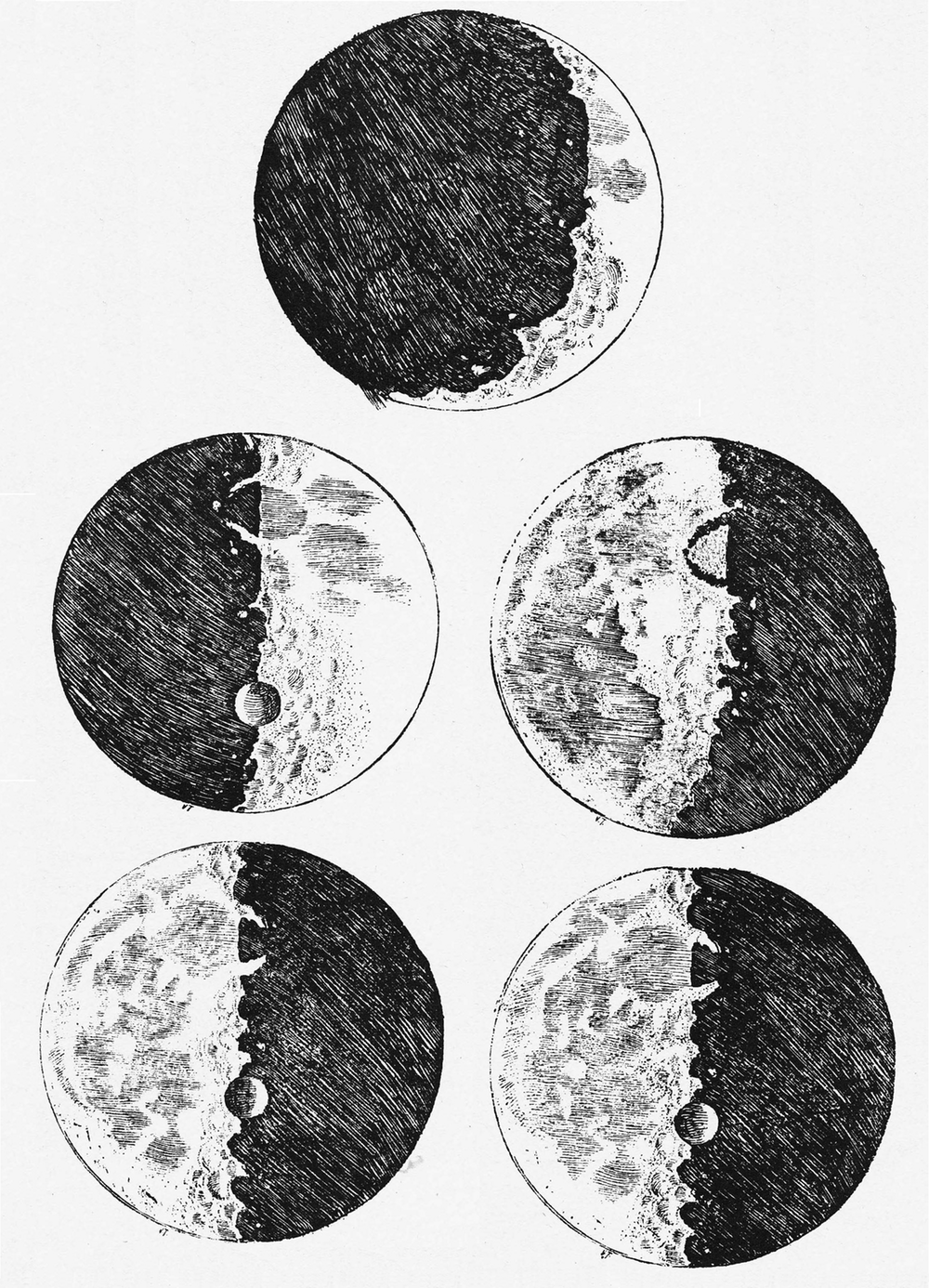

Galileo’s Starry Messenger, published in 1610, even featured some sketches of the eerie moon relief. In 1620, Ben Jonson’s masque, News from the New World Discovered in the Moon, was performed before King James I, entertaining the court with satire but also elucidating the newest astronomical viewpoints.

It was in the context of this moon fervour that John Wilkins, a 24-year-old graduate of Oxford University, published in 1638 the first edition of his book The Discovery of a World in the Moone. The book popularised Galileo’s description of the moon as a solid and habitable world.

A World in the Moone

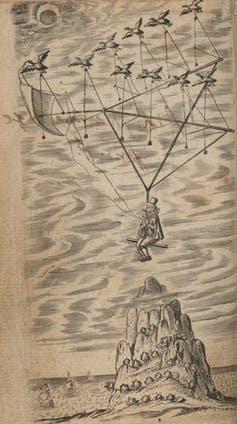

When preparing the much edited and lengthened second edition of The Discovery, eventually published in 1640, Wilkins was impressed by Francis Godwin’s story The Man in the Moone, also appearing in 1638, in which a character named Domingo Gonzales is transported to the moon in a chariot towed by a flock of geese.

After reading this piece of 17th-century science fiction, Wilkins suggested that not only must occasional travel to the moon be possible, but also regular visits and habitation. The moon was the ultimate travelling destination of his time, and moon travel a technological achievement pushing the historical and providential limits for mankind.

Appreciating various fictional scenarios, Wilkins aimed to “raise up some spirits eminent for new attempts and strange inventions”, and to contemplate practical ways of “bringing the moon closer” by travelling through space. In the pragmatic tone of an artisan, the second edition of the Discovery ruminates on the technicalities:

“I do seriously, and upon good grounds, affirm it possible to make a flying chariot.”

Wilkins describes and designs various flying apparatuses driven by manpower, or towed by majestic exotic birds, and even imagines an engine to be contrived on the same principles as the legendary mechanical doves and eagles.

He was also alerted to the challenges of moon travel, and even expressed a slight vexation that divine providence did not endow the human body with any natural means of flying. Enumerating the impediments to flight from the Earth, he humorously warns that there won’t be any "castles in the air to receive poor pilgrims, or errant knights”. He discusses the nature of gravity, and how difficult it would be to bring food and water to the moon, and to survive the cold and thin lunar air.

In perspective

But Wilkins also states with perfect assurance that the ways of conveyance through space would eventually be discovered. He predicts that “as soon as the art of flying is found out”, humans “will make one of the first colonies, that shall transplant into that other world”, all glorifying the future of air travel.

The Discovery ends with Wilkins prophesying that posterity will likely be surprised at the ignorance of his age. But this isn’t the feeling kindled in his modern readership – although many of his conclusions about the moon are indeed mistaken. Even though the answers were premature, our contemporary investigations of the moon still follow the same trajectory of questions as did his Space Odyssey 1640: the presence of water, the possibilities for regular travel and colonisation. Young John Wilkins meant to provoke the readers’ curiosity concerning “secret truths” about nature, and fulfilled this purpose for centuries ahead.

Space explorations tend to be viewed primarily as manifestations of spectacular – and, alas, costly – technologies. Is this not the reason why the moon flight program has been jammed for years? In the 17th century, motivation to design the means of travel to the moon was similar to our contemporary stimuli for space exploration as they were formulated at the dawn of the Apollo spaceflight program. People dreamed of pushing the boundaries of humankind, and of bringing to life a great deal of useful knowledge.

After all, it is not only machinery that drives human beings into space, but humanity’s curiosity and imagination prompting the desire to reach beyond the possible.

Maria Avxentevskaya is a researcher in early modern studies at Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments