Scientists blow a bubble that does not move – and it's a big deal

Being able to control a bubble could help doctors treat blood clots and prevent problems in nuclear power plants

It is a lesson learnt by generations of children who have had fun blowing bubbles – they wobble around all over the place and they never last long.

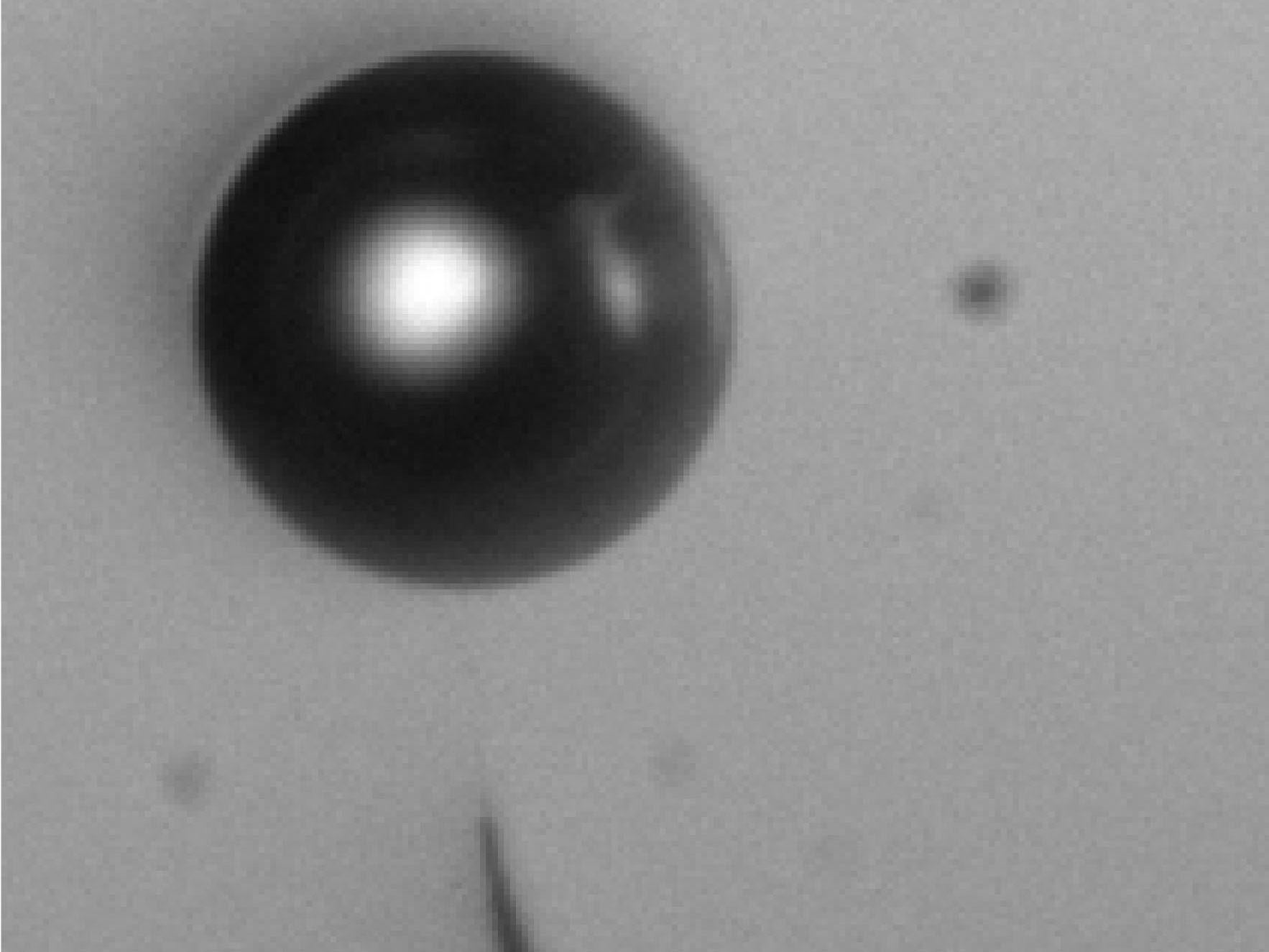

But now scientists in France have managed to immobilize a tiny bubble in water in a surprising breakthrough that could help doctors treat blood clots.

Normally bubbles in a liquid will naturally be pushed upwards, a phenomenon described by Archimedes in 250BC. “Any object, wholly or partially immersed in a fluid, is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object,” the great mathematician wrote.

And until now, no-one had found a way to stop this process from happening.

However, researchers at Aix-Marseille Université found they could create microbubbles by running electricity through a tiny electrode in water.

By changing the frequency of the electricity they discovered they could make the bubble stay a set distance from the electrode, according to a paper in the journal Applied Physics Letters.

So instead of slowly rising through the water, it would stay in a fixed position. And if they moved the electrode, the bubble went with it.

In a statement, the American Institute of Physics (AIP), which publishes the journal, said: “Controlling bubbles is a difficult process and one that many of us experienced in a simplistic form as young children wielding a bubble wand, trying to create bigger bubbles without popping them.”

The Aix-Marseille Université researchers “demonstrated they could immobilize a microbubble created from water electrolysis as if the Archimedes’ buoyant force that would normally push it to the surface didn't exist”, AIP said.

“It is a stable situation: No matter which direction the electrode moves, the bubble remains above and at the same distance from the electrode,” the statement added.

It is believed that while the surface of the bubble does not move, there is a significant amount of movement with hydrogen or oxygen molecules entering the immobilized bubble through its lower surface and leaving through the top.

The AIP added: “This new and surprising phenomenon … could lead to applications in medicine, the nuclear industry or micromanipulation technology.”

The statement said the controlling microbubbles was “critical to numerous applications in medicine”, including breaking up blood clots and deliberately blocking an artery during surgery to prevent blood loss.

It is also important in the nuclear industry where tiny bubbles in liquid coolants can cause a problem.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments