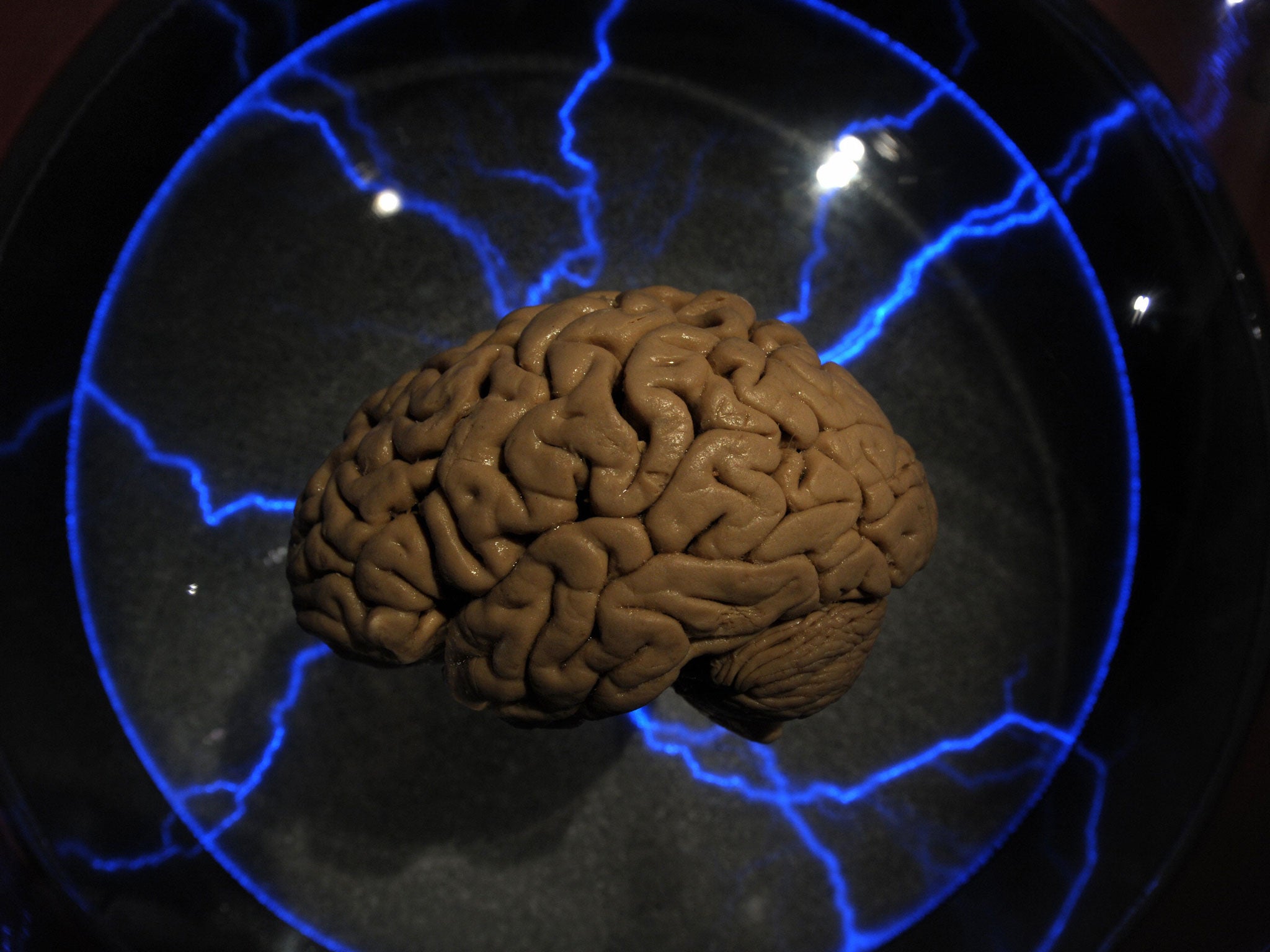

Brain treats rejection like physical pain say scientists

Human brain treats rejection in a similar way to the way it processes pain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The human brain treats rejection in a similar way to the way it process physical pain, new research has suggested.

A scientific study conducted by the University of Michigan Medical School has shown that the brain uses a similar reaction to ease the pain of social rejection as it does to deal with pain caused by physical injury.

A team led by Dr David T. Hsu also found that people who showed high levels of resilience on a personality test also had higher levels of natural painkiller activation.

When the body experiences physical pain, the brain releases chemical opioids into the empty space between neurons, which “dampens” pain signals.

The team asked 18 adults to look at photos and fictitious personal profiles of hundreds of other adults. Each selected some who they might be most interested in romantically, as they would do on a typical online dating website.

Afterwards, when the participants were lying in a PET scanner, they were informed that the individuals they found attractive and interesting were not interested in them.

Researchers monitored the mu-opioid receptor system in the brain, which the team have been examining for the last decade in response to physical pain.

The brain scans of participants who were experiencing this form of social rejection showed highly active opioid systems, meaning the brain was releasing its natural painkiller.

Before beginning the study, researchers told participants that the “dating” profiles were not real, and neither was the “rejection.” However, the simulated social rejection was enough to cause both an emotional and opioid response.

“This is the first study to peer into the human brain to show that the opioid system is activated during social rejection,” Dr Hsu said.

“This suggests that opioid release in this structure during social rejection may be protective or adaptive.

“In general, opioids have been known to be released during social distress and isolation in animals, but where this occurs in the human brain has not been shown until now.”

Dr Hsu noted that the underlying personality of the participants appeared to play a role in how active their opioid system response was.

“Individuals who scored high for the resiliency trait on a personality questionnaire tended to be capable of more opioid release during social rejection, especially in the amygdala,” he said.

“This suggests that opioid release in this structure during social rejection may be protective or adaptive."

He added: “It is possible that those with depression or social anxiety are less capable of releasing opioids during times of social distress, and therefore do not recover as quickly or fully from a negative social experience."

The team concluded that the brain pathways activated by physical and social pain are similar. Studying this response, and the variation between people, could aid understanding of depression and anxiety.

New opioids could therefore potentially be developed as effective treatments for depression and anxiety.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments