Bones under the hammer: Fossil fetish spurs collectors' market

Forget fine wines and fast cars – today's millionaires prefer collecting dinosaur skeletons. But are they pricing museums out of the market? Rob Sharp reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

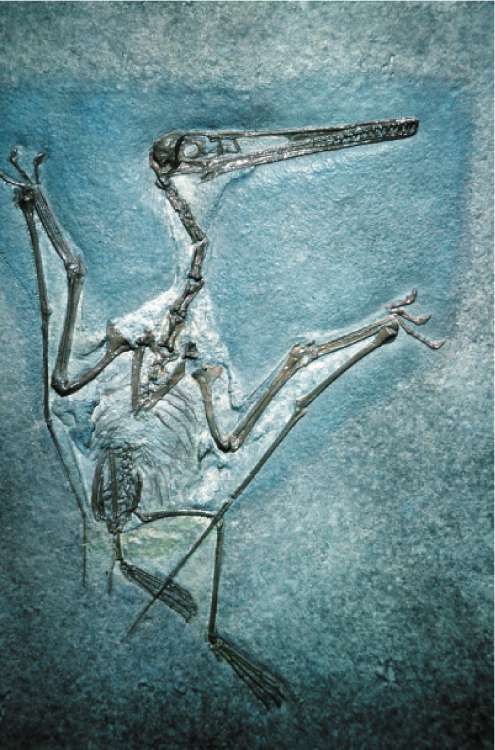

Your support makes all the difference.Dinosaurs are scary. Skeletons, even more so. So a dinosaur skeleton, you'd think, would make most run a mile. But despite their rictus grins and rattling bones, such objects are proving a hit with the rich and famous, always searching for something new to jazz up the country pile or Beverly Hills mansion.

Moneyed collectors are flocking to fossil auctions like never before. Just look at the catalogues of major auction houses over the past six months. In April, a 65-million-year-old Triceratops skeleton went under the hammer in Paris, and sold for a cool £400,000. In March, a prehistoric Siberian mammoth fetched an equally jaw-dropping £200,000 in New York.

With Christie's holding regular dinosaur auctions in the French capital, and similar events being held at Bonhams and fellow auctioneer Chait in Manhattan, there are more opportunities then ever to pick up a bony memento. And they are attracting their fair share of star power.

Among those with a dino fetish are the actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Nicholas Cage, who locked horns in a bidding war to obtain the head of a Tyrannosaurus bataar (the Asian cousin of T rex). Ron Howard, the Oscar-winning director of A Beautiful Mind, is also a fan. Bonhams says its client lists include a raft of Hollywood A-listers, captains of industry and royalty.

But here's the bad news: those who can't afford to keep up with escalating prices are losing out. This includes Britain's museums, whose budgets are pitiful compared to your average Hollywood hotshot or shipping magnate in pursuit of his next palaeontology fix.

"We are increasingly seeing clients coming to our contemporary art or furniture auctions and discovering natural history," says Fleur de Nicolay, fossil auction specialist at the Paris office of Christie's. "Our furniture collectors might be searching for a more decorative piece that would look good next to a master painting. That is why we mix our sales of fossils with our furniture sales. People realise that they are mostly decorative objects, especially ammonites or a fish fossil."

They are more than just decoration, however; dinosaur bones are sound business investments. According to a recent Wall Street Journal report, the price of a Triceratops skull in good condition has increased tenfold over the past decade, to a whopping £125,000. Log on to online auction sites like eBay and search for "fossils"; you'll find any number of ammonites and trilobites (extinct arthropods) up for grabs, and there's even a dinosaur skull for sale.

The people selling them are no doubt spurred on by the knowledge that the most expensive fossil sale ever, in 1997, fetched £4m for one lucky vendor who flogged the remains of a 65-million-year-old dinosaur called Sue, after its finder.

So how can museums compete? The Natural History Museum in London says its fixed annual budget for buying all its science specimens is £30,000. "Private collectors have always been a part of the landscape we work in; indeed the Museum's collection was founded from a private collection," says Angela Milner, the associate keeper of palaeontology at the museum. "But, as a publicly funded institution, we only have limited funds with which to buy specimens and in some cases we may well be priced out of the market."

Richard Edmonds, earth science manager at the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Centre in Dorset, agrees that there is a problem here. "I think it's worth drawing an analogy between funding of the arts and funding for science. If you compare the millions of pounds spent on acquiring the work of modern artists... well, in Dorset, that money would buy us all of the specimens ever found down here, as well as build us a museum in which to show them off."

However, unlike art – in which there is a certain amount of craftsmanship involved – fossil-finding involves an element of luck. The people who bring the objects to light can be amateurs who spend days scouring coastlines in search of fossils released naturally from eroding cliffs. According to Edmonds, any fossils found on the ground belong to the owner of that land. But, he says – and this is what allows the collectors to operate – there is an argument to be made that any fossils lying on the ground have been "abandoned" and are fair game.

Where the problems set in, however, is that there is no guarantee that such objects would have been acquired ethically, for instance, through informing the scientific community of the find. The Plymouth University palaeontologist Kevin Page, who does research on the Dorset coast, says: "My bank account won't stretch to buying back the fossils which have been removed. In theory, our society values our heritage; some of it is of world status. And we are treating it as a commodity. This is unique in Europe where most countries have heritage laws that they enforce. If you say we could sell fossils, why shouldn't we sell bird's eggs? We put in a lot of effort protecting other areas of heritage." Some people believe that science should be beyond the reach of capitalism, even if collectors are operating within the law.

Another issue, according to Scottish Natural Heritage, is that unscrupulous fossil-hunters have damaged heritage sites, sometimes by using power tools or dynamite to unearth and plunder valuable specimens. They sell their finds on the black market, estimated to be worth £50m globally. These specimens often end up being sold alongside the legitimate finds.

Thankfully, however, the vast majority of people collecting fossils are doing so for the right reasons and in the right way. Dr Colin Prosser, principal geologist at the agency Natural England, says: "We are happy for people to collect fossils responsibly. We could encourage it as good practice. Always get permission from the landowner, and avoid dangerous cliffs. Also, make a note of where you get the fossil from. There are many sites where fossil collecting does not damage the source of the resource."

A good example of responsible collecting yielding a public benefit was seen recently in Dorset. Here, the skeleton of a scelidosaurus (a plant-eater) was unearthed several years ago. It is set to go display at Bristol Museum later this month. The professional fossil-hunter David Sole found the skeleton in Charmouth – and he is loaning it rather than selling it at its market value (thought to be about £100,000).

Another collector operating in the area has perfected a technique for extracting entire skeletons of ichthyosaurs (giant marine reptiles) from rock beds. Richard Edmonds says the collector could receive up to £24,000 per skeleton, but adds that the sum could be justified given the effort involved in discovering, excavating and preserving the fossil finds.

Edmonds adds: "If people did not collect fossils from our beaches, the sea would take them away and we would never have known they existed. It is not so simple as saying that taking fossils as a bad thing. As long as people make the scientists aware of what they have found, then we are happy to let them keep it. Many people such as David Attenborough were inspired into a love of the natural world through fossil-hunting. As long as it doesn't deplete the site, it's good."

People can also be encouraged to behave properly through "voluntary registration schemes". Scotland has the Scottish Fossil Code, which tries to ensure that fossil-hunters keep the scientists informed about what they're doing and what they find. "Crucially, it will encourage the responsible collecting and care of fossils," says Colin Galbraith, the director of policy and advice for Scottish Natural History.

But, wherever the fossils, bones and skeletons have come from, one thing is sure; lots of Jurassic parts are set to make an appearance at an auction house near you soon.

Jurassic parts: how much fossils fetch at auction

*The largest and best-preserved Tyrannosaurus rex ever discovered was found in 1990 by the palaeontologist Sue Hendrickson, and named after her. It was sold at a Sotheby's auction in 1997 for £4m, the highest sum ever paid for a dinosaur specimen. It is now on display at the Field Museum in Chicago.

*The second near-complete skeleton of a large dinosaur ever to go for public auction, a Triceratops, went on sale in April at Christie's in Paris. The dinosaur, with its missing bones replaced by resin replicas, was the star attraction at a "monster sale". It was dug up by a rancher in North Dakota and bought by an unnamed "Western European" collector four years ago.

*The most expensive fossilised skeleton ever sold in Britain was a plesiosaur that fetched £35,000 in London in 2005. The plesiosaur – an aquatic reptile, and not a true dinosaur – was distinguished by what is believed to have been its small head, long and slender neck, broad turtle-like body and paddle-like legs.

*Other objects recently up for auction include a plesiosaur tooth in opal from 110 million years ago, and a tibia from a two-metre-high apatosaurus (the long-necked dinosaur formerly known as the brontosaurus) from the Jurassic period, about 150 million years ago. Many of the lots at the Christie's sale in Paris were taken from collections of fossils assembled by European aristocrats in the 18th and 19th centuries, a time when amassing large collections of fossils was fashionable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments