The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The dimming of Betelgeuse: ‘We have directly witnessed the formation of so-called stardust’

The super star has spent millions of years burning — and now, thanks to a burp, it’s on the brink of doom, writes Dennis Overbye

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Betelgeuse, to put it most politely, burped.

In the autumn of 2019 the star, a red supergiant at the shoulder of the constellation Orion the Hunter, began to dim drastically to less than half its usual brightness, and some astronomers worried — or perhaps were hoping — that it would explode in a supernova.

Astronomers now say that dust was the culprit in the Great Dimming and that Betelgeuse itself was responsible for that dust. A giant blob of gas erupted from the star, the story goes, and then cooled off and condensed into solid particles that temporarily veiled their origin.

“We have directly witnessed the formation of so-called stardust,” Miguel Montarges, an astrophysicist at the Paris Observatory, says in a statement issued by the European Southern Observatory. He and Emily Cannon of Catholic University Leuven, in Belgium, were the leaders of an international team that studied Betelgeuse during the Great Dimming with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) on Cerro Paranal, in Chile.

Parts of the star, they found, were only one-tenth as bright as normal and markedly cooler than the rest of the surface, enabling the expelled blob to cool and condense into stardust. They reported their results on Wednesday in Nature.

The research, they say, shows that such dust formation can occur very quickly and near a star’s surface. From there it can wind up anywhere; as the old saying goes, we are all made from stardust.

“The dust expelled from cool evolved stars, such as the ejection we’ve just witnessed, could go on to become the building blocks of terrestrial planets and life,” Cannon says in the statement.

For once, we were seeing the appearance of a star changing in real time on a scale of weeks

Their new results would seem to bolster findings reported a year ago by Andrea Dupree of the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics and her colleagues, who detected an upwelling of material on Betelgeuse in the summer of 2019.

“We saw the material moving out through the chromosphere in the south in September to November 2019,” Dupree writes in an email. She refers to the expulsion as “a sneeze.” She and Montarges were co-authors on each other’s papers.

But Edward Guinan, of Villanova University, who has followed Betelgeuse intently, was more measured in this enthusiasm. Three other studies favour the growth of cool regions on the surface of the star to explain the significant decrease in light.

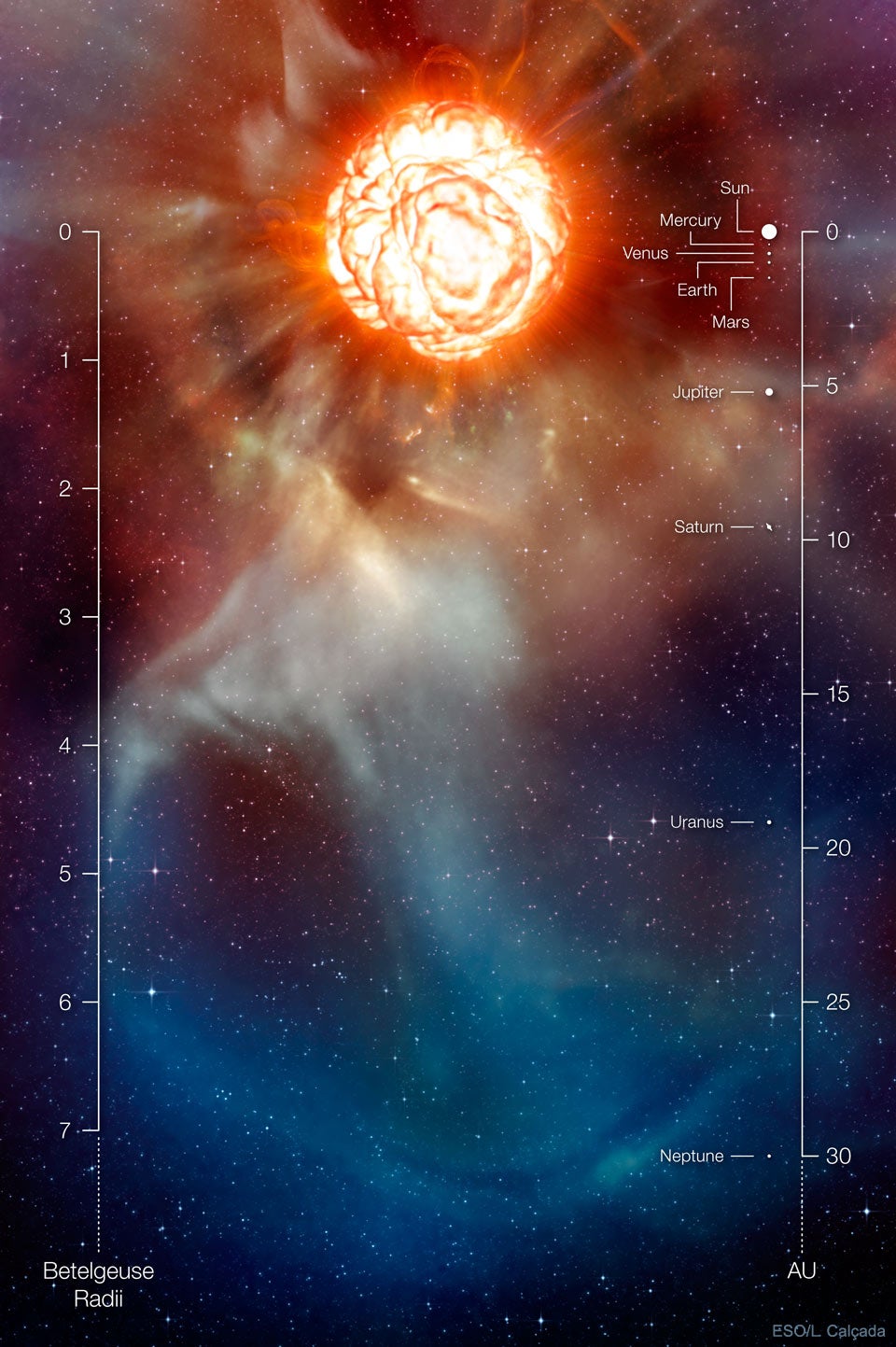

Betelgeuse is a so-called red supergiant, 887 times as large as our own sun. Its surface, like the sun’s, resembles boiling oatmeal as blobs of gas rise, conveying heat and energy. Such blobs on the sun are often described by American astronomers as comparable in size to Texas.

“In France, we say that the sun’s convective cells are as big as France,” Montarges says in an email. “It’s really funny to see each country comparison.”

But on Betelgeuse, he says, those blobs are half as wide as the star itself, 350 million miles across. There are only a few of them at any given time.

Betelgeuse also undergoes a 400-day cycle of pulsation, dimming and brightening, although usually not nearly to the extreme it just exhibited.

Montarges and Cannon began to observe Betelgeuse in 2019 with a special instrument called SPHERE on the VLT, which allowed them to follow changes on the surface of the distant star in high resolution.

“For once, we were seeing the appearance of a star changing in real time on a scale of weeks,” Montarges says in his statement. In late 2019 they observed that one part of the star was only one-tenth as bright as it had been the year before and about 300 to 500 kelvin — 540 to 900 degrees Fahrenheit (or 282 to 482C)— cooler than the rest of the star.

Montarges and his colleagues reason that the boiling star ejected a blob of gas months if not years before the Great Dimming. The gas cloud was about as big as the star. It hung around Betelgeuse as gas because the region around the star was still too warm for the cloud to condense into dust until the next cycle of shrinkage and cooling.

“Then the photosphere cooled,” Montarges notes, “probably in the initially bright region that ejected the clump.” That would have lowered the ambient temperature in the cloud enough for dust to nucleate and shroud its birthplace.

“This adventure with Betelgeuse was really exciting,” Montarges says.

And so, for now, Betelgeuse is back to normal — whatever “normal” means to a star on the brink of doom. That the star will eventually blow up is certain. Betelgeuse, pronounced “beetle-juice” and also known as Alpha Orionis, is at least 10 times and maybe 20 times as massive as the sun. If it were placed in our solar system, it would engulf everything out to Jupiter’s orbit.

Red supergiants are stars in the last violent stages of their evolution. Betelgeuse has already spent millions of years burning primordial hydrogen and transforming it into helium, the next lightest element. The helium is burning into more massive elements. Once the core of the star becomes solid iron, sometime within the next 100,000 years, the star will collapse and then rebound in a supernova explosion, probably leaving behind a dense nugget called a neutron star.

That will be quite a show. The last bright supernova in our galaxy occurred in 1604 and was as bright as Venus in the sky, Guinan says.

He says that he still glances at Betelgeuse every day but that lately he has become convinced that an even larger supergiant known as VY Canis Majoris is more likely to blow first.

“I have been observing since 1980,” he says, “and I am now 79 and don’t have much more time left to see these supernovae.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments