Benefits of 'three-parent babies' will likely outweigh the risks, experts claim

Senior science advisers write in praise of controversial mitochondrial transfer technique

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The medical benefits of creating so-called “three-parent” babies are likely to outweigh any risks, according to two senior science advisers who have defended their recommendation to proceed with caution on the controversial in vitro fertilisation (IVF) technique.

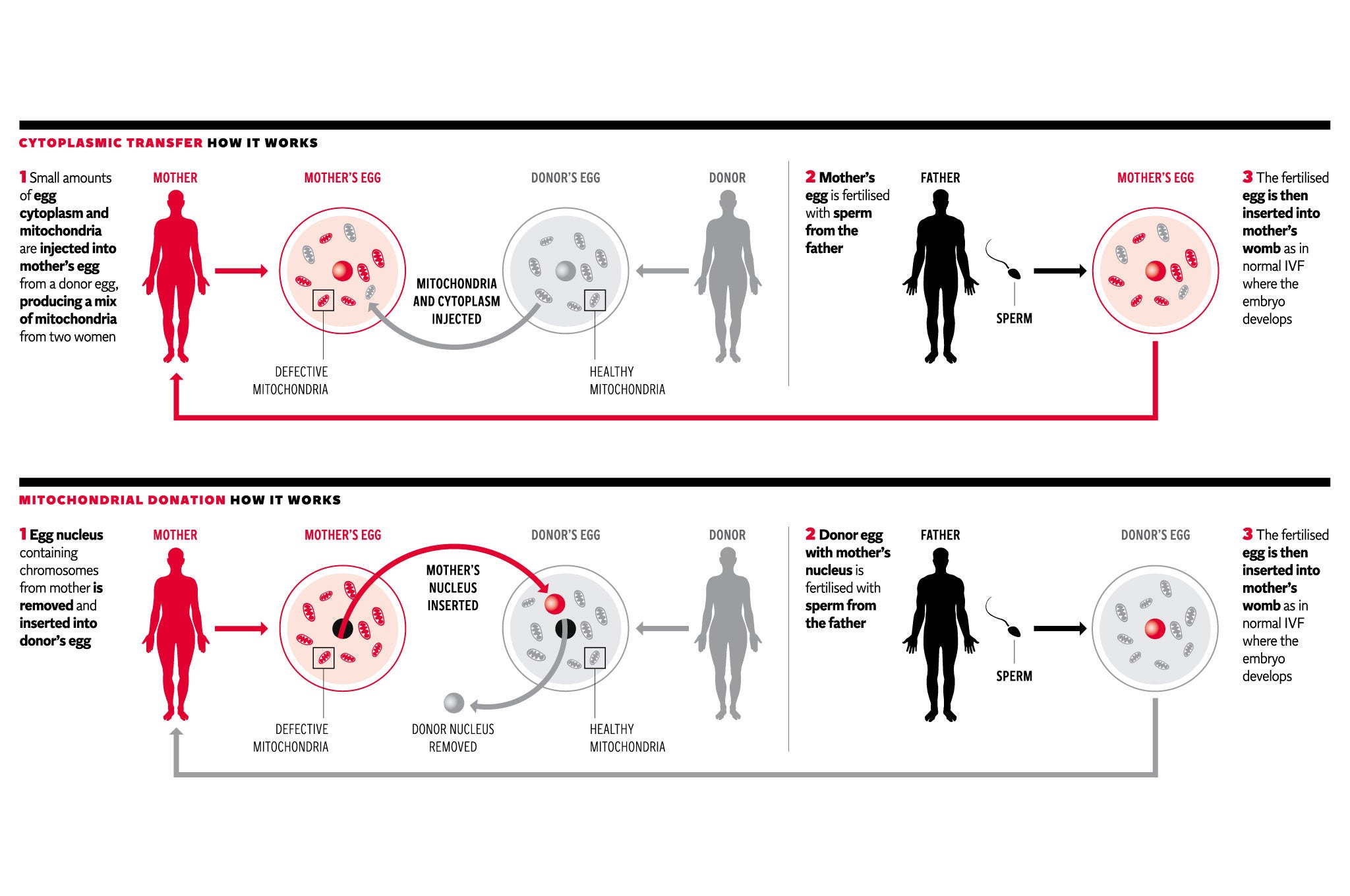

Doubts over the safety of mitochondrial transfer, where the defective “power packs” of a woman’s egg cell are replaced with those from a healthy donor egg, are misplaced, according to Professors Robin Lovell-Badge and Peter Braude, who both sit on an expert panel advising the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA).

Creating IVF embryos with the help of healthy mitochondria from a third party is a viable way of offering women affected by mitochondrial disorders the opportunity of having their own biological children who will be free of the diseases, they said.

“For couples with mitochondrial DNA mutations, there are no alternatives that allow the couple to have genetically related children free of mitochondrial disease,” the two professors write in a joint letter to an American colleague.

“No medical first-in-man technique is ever without risk, whether this be heart or kidney transplants, or the first IVF or the first embryo biopsy for pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. The risk of treatment must be balanced against the certainty of adverse outcome without,” they say.

Professor Lovell-Badge is an authority on embryology and stem cells at the Medical Research Council’s National Institute for Medical Research in north London, and Professor Braude is an expert on genetic testing and IVF at King’s College London. They have spent more than three years reviewing the scientific literature on all issues relating to mitochondrial transfer.

In their letter, the two professors explained that they have been at the forefront of the HFEA’s long deliberations into the science of mitochondrial transfer but have failed to find any convincing evidence to suggest that the technique will be unsafe in humans.

Parliament is expected to vote soon on whether to allow the HFEA to licence mitochondrial transfer which could mean that Britain could soon become the first country in the world to legalise the procedure in fertility clinics treating families with a history of mitochondrial diseases.

In an interview last week with The Independent, Professor Evan Snyder, who chairs a similar scientific panel advising the US Food and Drug Administration on mitochondrial transfer, warned that further research on safety needs to be done before clinical trials could begin in America – which could take between two and five more years.

However, Professors Lovell-Badge and Braude point out that the legal situation in Britain is very different to that in the United States, where creating IVF embryos from three people is not illegal, and all that the Parliamentary vote will do is to put the HFEA on an equal footing to the FDA.

“First, it is important to appreciate that the regulatory process in the UK by the HFEA is different from that in the US. In contrast to the US, where there is no federal regulation of IVF technology, in the UK we have specific legislation that deals with the use of gametes [sperm and eggs] and human embryos in vitro,” they write.

“Thus these Parliamentary regulations are in essence ‘enabling legislation’ which would simply take the UK onto the same footing as the current situation in the US, where the safety and efficacy data determine whether clinical application should be allowed,” they say.

“We are therefore not rushing ahead of the US, and the same issues that concern you and the FDA committee are those that exercised us in our deliberations,” they add.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments