How our autistic ancestors played an important role in human evolution

Thousands of years ago, people who displayed autistic traits may have been highly respected in society for their skills and talents

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When you think of someone with autism, what do you think of? It might be someone with a special set of talents or unique skills – such as natural artistic ability or a remarkable memory. It could also be someone with enhanced abilities in engineering or mathematics, or an increased focus on detail.

This is because despite all the negative stories of an “epidemic of autism” most of us recognise that people with autism spectrum conditions bring a whole range of valued skills and talents – both technical and social – to the workplace and beyond.

Research has also shown that a high number of people not diagnosed with autism have autistic traits. So although many of these people have not been officially diagnosed, they might be were they to go for autism-related tests. These people were unaware they have these traits, don’t complain of any unhappiness, and tend to feel that many of their particular traits are often an advantage.

This is what we mean when we talk about the autism spectrum – we are all “a bit autistic” – and we all fit somewhere along a spectrum of traits.

And we know through genetic research that autism and autistic traits have been part of what makes us human for a long time.

Research has shown that some key autism genes are part of a shared ape heritage, which predates the “split” that led us along a “human” path. This was when our ancient ape ancestors separated from other apes that are alive today. Other autism genes are more recent in evolutionary terms – though they are still more than 100,000 years old.

Research has also shown that autism for the most part is highly hereditary. Though a third of the cases of autism can be put down to the random appearance of “genetic mistakes” or spontaneously occurring mutations, high rates of autism are generally found in certain families. And for many of these families this dash of autism can bring some advantages.

All of this suggests that autism is with us for a reason. And as our recent book and journal paper show, ancestors with autism played an important role in their social groups through human evolution because of their unique skills and talents.

Going back thousands of years, people who displayed autistic traits would not only have been accepted by their societies, but could have been highly respected.

Many people with autism have exceptional memory skills, heightened perception in realms of vision, taste and smell and in some contexts, an enhanced understanding of natural systems such as animal behaviour. And the incorporation of some of these skills into a community would have played a vital role in the development of specialists. It is very likely these specialists would then have become vitally important for the survival of the group.

One anthropological study of reindeer herders said: “The extraordinary old grandfather had a detailed knowledge of the parentage, medical history and moods of each one of the 2,600 animals in the herd. He was more comfortable in the company of reindeer than of humans, and always pitched his tent some way from everyone else and cooked for himself. His son worked in the herd and had been joined for the summer by his own teenage sons, Zhenya and young Sergei.”

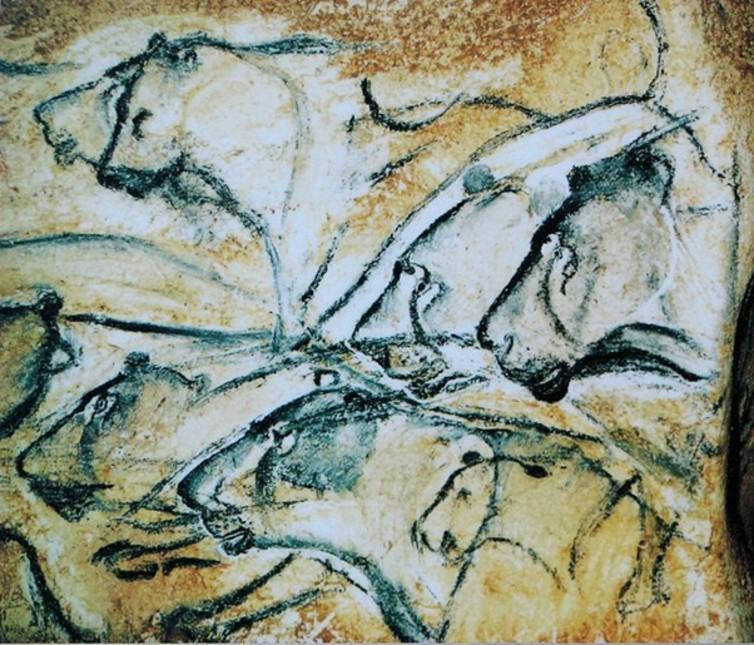

Further evidence can be found in traits shared between some cave art and talented autistic artists – such as those paintings found in the Chauvet Cave, in southern France. This contains some of the best preserved figurative cave paintings in the world.

The paintings show exceptional realism, remarkable memory skills, strong attention to detail, along with a focus on parts rather than wholes.

These autistic traits can also be found in talented artists who don’t have autism but they are much more common in talented autistic artists.

But unfortunately despite the potential evidence, archaeology and narratives about human origins have been slow to catch up. Diversity has never been a part of our reconstructions of human origins. It has taken researchers a long time to move beyond the image of a man evolving from an ape-like form that we so typically associate with evolution.

It is only relatively recently that women have been recognised as playing a key role in our evolutionary past – before this evolution narratives tended to focus on the role of men. So it’s no wonder that including autism – something which is still seen as a “disorder” by some – is considered to be controversial.

And this is undoubtedly why arguments about the inclusion of autism and the way it must have influenced such art have been ridiculed.

But given what we know, it is clearly time for a reappraisal of what autism has brought to human origins. Michael Fitzgerald, the first professor of child and adolescent psychiatry in Ireland to specialise in autism spectrum disorder, boldly claimed in an interview in 2006 that: “All human evolution was driven by slightly autistic Asperger’s and autistic people. The human race would still be sitting around in caves chattering to each other if it were not for them.”

And while I wouldn’t go that far, I have to agree that without that “dash of autism” in our human communities, we probably wouldn’t be where we are today.

enior lecturer in the archaeology of human origins at the University of York. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments