Australian gem is 'oldest piece of Earth ever found' - and shows life could have formed on our planet earlier than anyone thought possible

Tiny piece of zircon shows Earth's crust formed at least 4.4 billion years ago - and life could have appeared not long after that

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A gem found on a sheep ranch in Australia has been found to have formed 4.4 billion years ago - making it the oldest piece of our planet ever recorded.

The discovery alters our understanding of the early stages in Earth's formation, and shows that a crust formed on its surface significantly quicker than previously thought.

To put it in context, the solar system itself only came into existence around 4.56 billion years ago, meaning it took at most 160 million years for our planet to develop a crust.

Writing in the journal Nature Geoscience, a team of experts from the University of Wisconsin said their findings showed that early Earth was a more hospitable place than previously thought - and that there is no reason life could not have appeared around 4.3 billion years ago.

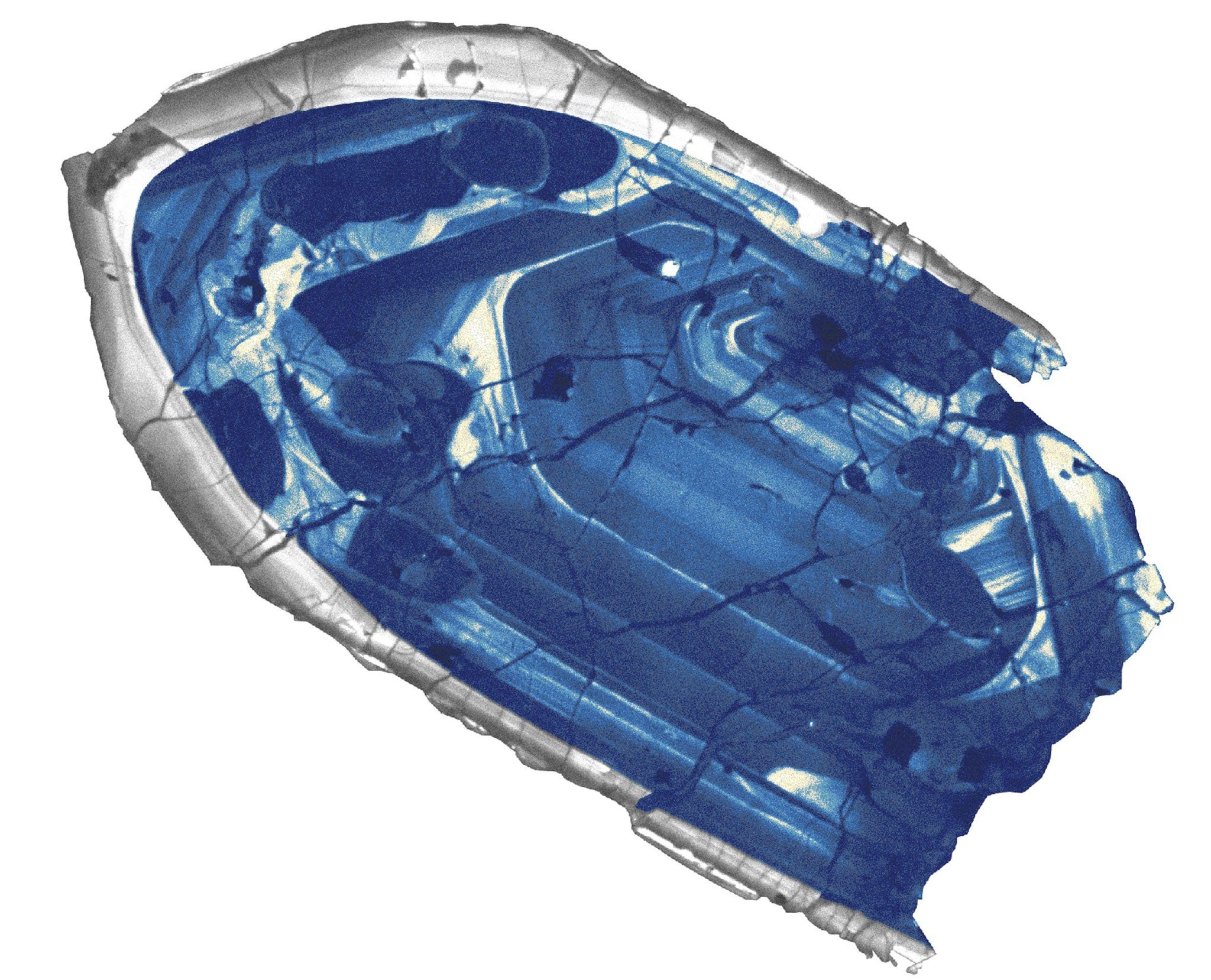

The results are so significant that scientists waited to use two different age-determining techniques on the tiny zircon crystal, found in western Australia in 2001, before publishing their report.

They first used a widely-accepted dating technique based on determining the radioactive decay of uranium to lead in a mineral sample.

But because some scientists hypothesised that this might give a false date due to the potential for movement of lead atoms within the crystal over time, the researchers turned to a second sophisticated method to verify the finding.

They used a technique known as atom-probe tomography that was able to identify individual atoms of lead in the crystal and determine their mass, and confirmed that the zircon was indeed 4.4 billion years old.

The Earth itself formed as a ball of molten rock 4.5 billion years ago, and Wisconsin geoscience professor and report lead John Valley said their findings support the notion of a "cool early Earth" where temperatures were low enough to sustain oceans, and perhaps life, earlier than previously thought.

This period of Earth history is known as the Hadean eon, named after the ancient Greek god of the underworld because of its apparently hellish conditions.

"One of the things that we're really interested in is: when did the Earth first become habitable for life? When did it cool off enough that life might have emerged?" Professor Valley told the Reuters news agency.

The discovery that the zircon crystal, and thereby the formation of the crust, dates from 4.4 billion years ago suggests that the planet was perhaps capable of sustaining microbial life 4.3 billion years ago, Valley said.

"We have no evidence that life existed then. We have no evidence that it didn't. But there is no reason why life could not have existed on Earth 4.3 billion years ago," he added.

The oldest fossil records of life are stromatolites produced by an archaic form of bacteria from about 3.4 billion years ago.

The zircon was extracted in 2001 from a rock outcrop in Australia's Jack Hills region. For a rock of such importance, it is rather small. It measures only about 200 by 400 microns, about twice the diameter of a human hair.

"Zircons can be large and very pretty. But the ones we work on are small and not especially attractive, except to a geologist," Professor Valley said. "If you held it in the palm of your hand, if you have good eyesight you could see it without a magnifying glass."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments