Roman-era rabbit bone reveals creatures arrived in Britain 1,000 years earlier than thought

Rabbits only established in wild in 12th century in UK

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The remains of the UK’s earliest rabbit have been found at a Roman Palace in West Sussex.

The discovery at Fishbourne Roman Palace reveals the animals, which are native to France and Spain, arrived in Britain 1,000 years earlier than previously thought.

The species is a very recent addition to British wildlife, as they were not established in the wild until the mid to late 12th century, and it was previously thought they had first arrived a couple of hundred years earlier.

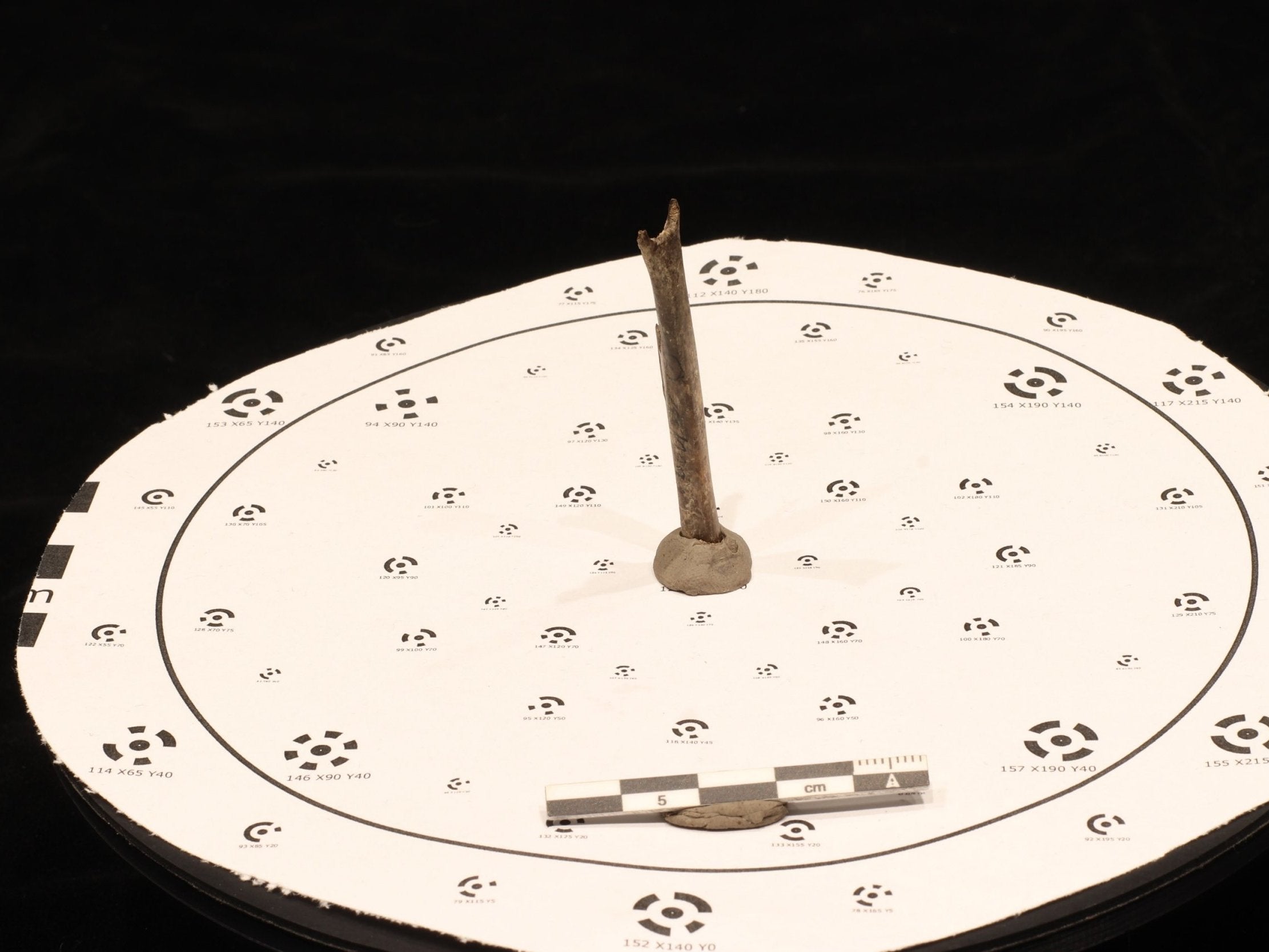

But radiocarbon dating of a 4cm tibia bone indicate the rabbit was alive in 1AD.

The small bone was unearthed during excavations at the palace in 1964, but had been unrecognised at the time.

In 2017, Historic England zooarchaeologist Dr Fay Worley recognised the bone as possibly belonging to a rabbit, and subsequent genetic analysis proved her to be correct.

The bone does not show signs of the animal having been butchered, and further analysis suggested the animal may have been kept in confinement.

Academics from the Universities of Exeter, Oxford and Leicester carried out the analyses.

Further research is continuing to determine where the animal came from and whether it is related to present-day rabbits.

Dr Worley said: “I was excited to find a rabbit bone from a Roman deposit, and thrilled when the radiocarbon date confirmed that it isn’t from a modern rabbit that had burrowed in.

“This find will change how we interpret Roman remains and highlights that new information awaits discovery in museum collections.”

The researchers are also trying to shed light on the origins of Easter celebrations in the UK.

Professor Naomi Sykes, from the University of Exeter, said: “This is a tremendously exciting discovery and this very early rabbit is already revealing new insights into the history of the Easter traditions we are all enjoying this week.

“The bone fragment was very small, meaning it was overlooked for decades, and modern research techniques mean we can learn about its date and genetic background as well.

“We are looking forward to telling people about our ongoing research this week. There’s a lot we don’t know about the origins of Easter, and we’re learning more every day.”

It is not clear how, when or why the rabbit became linked to the Easter festival, although it could be due to the spread of Christian religious beliefs.

The folkloric figure of the Easter Bunny bringing eggs for children is closely linked to German traditions.

Additional reporting by PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments