Neanderthals, the world’s first misunderstood artists

Cave paintings in Spain were made by Neanderthals, not modern humans, archaeologists report. The findings add to evidence that Neanderthals were capable of symbolic thought and perhaps language

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s long been an insult to be called a Neanderthal. But the more these elusive, vanished people have been studied, the more respect they’ve gained among scientists.

Last week, a team of researchers offered compelling evidence that Neanderthals bore one of the chief hallmarks of mental sophistication: they could paint cave art. That talent suggests that Neanderthals could think in symbols and may have achieved other milestones not preserved in the fossil record.

“When you have symbols, then you have language,” says Joao Zilhao, an archaeologist at the University of Barcelona and co-author of the new study.

When Neanderthal fossils first came to light in the mid-1800s, researchers were struck by the low, thick brow-ridge on their skulls. Later discoveries showed Neanderthals to have brains as big as our own, but bodies that were shorter and stockier.

By the early 1900s, scientists were describing Neanderthals as gorilla-like beasts, an extinct branch of humanity that could not compete with slender, brilliant humans. Yet evidence from both fossils and DNA indicates that Neanderthals and living humans descend from a common ancestor who lived about 600,000 years ago. Our own branch probably lived mostly in Africa.

For a few hundred thousand years after the split, the ancestors of living humans left behind such basic tools as stone axes for butchering carcasses and spear blades for hunting. But about 70,000 years ago, humans in Africa began showing signs of more abstract thinking. They coloured and pierced seashells, for example, possibly to wear as jewellery.

Modern humans began expanding from Africa, arriving in Europe roughly 45,000 years ago. By then, they had become capable of even more impressive symbolic creations, including ivory carvings and extravagant paintings on cave walls.

Neanderthals disappeared abruptly afterward, about 40,000 years ago, leaving behind a fossil record of their own from Spain to Siberia. Stockier than their African cousins, they appear to have evolved physical adaptations to harsh climates. They made stone tools of their own, which they used to hunt for game, including rhinos and other big mammals.

At first, researchers found no clear evidence of symbolic thought in Neanderthals. But in recent years, that picture has begun to change.

Neanderthals could use feathers and bird claws as ornaments, archaeologists found. But some scientists were sceptical about what these findings meant. Neanderthals might have lived near modern humans, after all, and spotted them making things. Neanderthals were smart enough to copy the ornaments, the thinking went – but not enough to invent them.

This debate was fuelled in part by the difficulty in pinning down a date for human fossils and artefacts.

To determine the age of cave paintings, for example, researchers have traditionally relied on radiocarbon dating. But that method only works if the paint contains carbon-bearing ingredients, such as charcoal. Red ochre, by contrast, can’t be dated this way.

Making matters worse, radiocarbon dating becomes increasingly unreliable beyond about 40,000 years.

Zilhao joined with archaeologists Alistair GW Pike of the University of Southampton and Dirk L Hoffmann, now at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, to see if the prehistory of European art could be brought into sharper focus.

Instead of studying radiocarbon, they would use a different clock to tell time.

As water seeps into caves, it may deposit milky crusts of minerals on the walls, known as flowstones. Flowstones contain tiny amounts of uranium, which slowly breaks down into thorium. The older a flowstone gets, the more thorium builds up inside it.

A flowstone covering a piece of cave art might give Zilhao and his colleagues a minimum age for its creation. The problem was that scientists usually needed big chunks to find enough uranium and thorium to measure. The flowstones on cave art were typically very small.

But Hoffman had been working on ways to drastically increase the sensitivity of the technology so that he could work with much smaller samples.

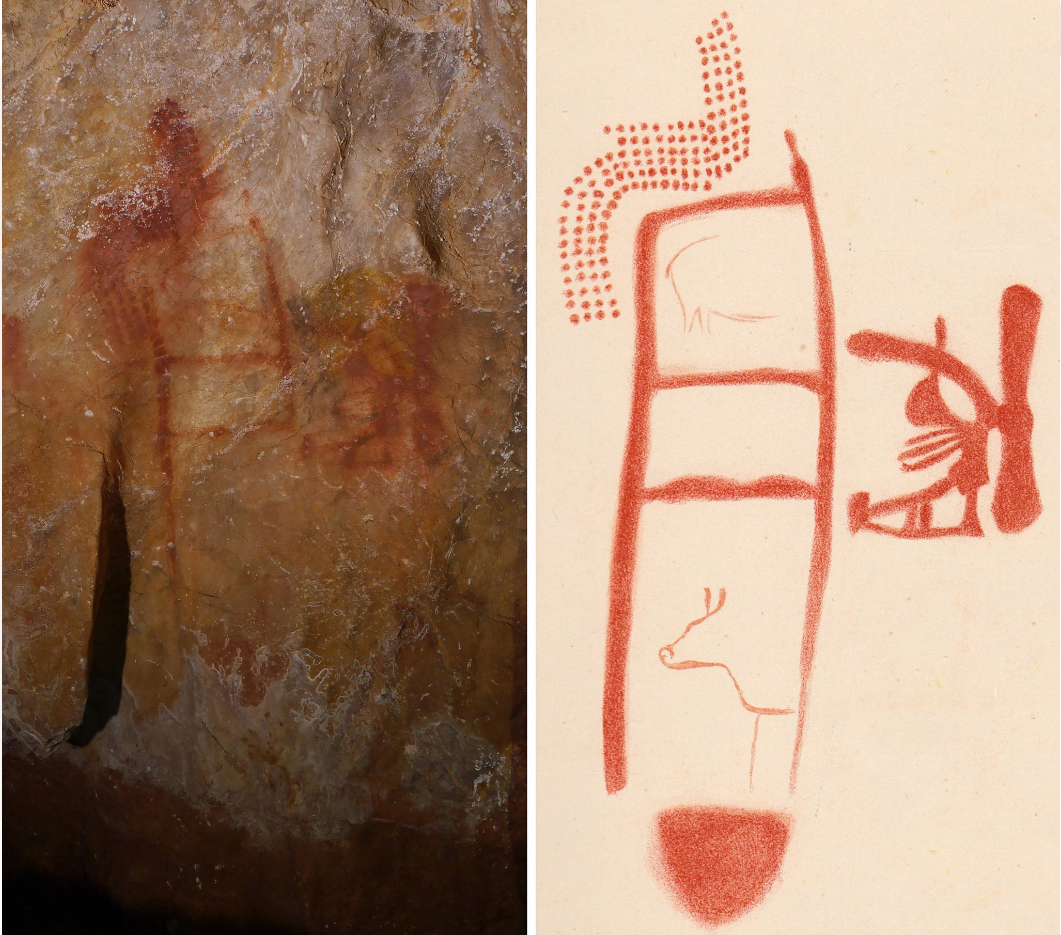

The researchers returned to caves in Spain where ancient paintings had been discovered over the past century. The artists had drawn abstract images on the cave walls, including long lines, patterns of dots and the outline of a human hand.

The team found flowstones covering parts of the artworks and scraped away samples for dating. In three caves, it turned out, some of the art was over 64,000 years old – about 20,000 years earlier than the first evidence of modern humans in Europe.

“They must have been made by Neanderthals,” says Pike.

Wil Roebroeks, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who was not involved in the new study, says the evidence was conclusive. “This constitutes a major breakthrough in the field of human evolution studies,” he says. “Neanderthal authorship of some cave art is a fact.”

Dating flowstones is a big advance on previous techniques for determining the age of cave art, but there is one major limitation: it can only assign a minimum age to cave paintings. Flowstones may have begun forming the day after a painting was finished – or 10,000 years afterward.

But a second study, which Zilhao and his colleagues published last week in the journal Science Advances, hints that Neanderthals might well have been painting long before 64,000 years ago.

The scientists travelled to a cave on the coast of Spain where Zilhao had earlier discovered shells that had been drilled with holes and painted with ochre.

In 2010, he and his colleagues had used radiocarbon dating to estimate the age of other shells in the same layer of rock at 45,000 to 50,000 years old. That result did not tell the team who made the ornaments. Neanderthals might be responsible, but it was also possible that the earliest modern humans in Europe made them.

And the uncertainties of radiocarbon dating also had left open the possibility that the shells were, in fact, far older.

Zilhao returned to the cave in order to try uranium dating. He and his colleagues discovered a layer of flowstone sitting atop the rock where they had found the shell jewellery. That flowstone turned out to be about 115,000 years old. The coloured, pierced shells themselves are probably not much older than that. Up until about 118,000 years ago, the cave was flooded, thanks to sea levels.

That finding provides strong evidence that the shells were made by Neanderthals.

The two new studies don’t just indicate that Neanderthals could make cave art and jewellery. They also establish that Neanderthals were making these things long before modern humans – a blow to the idea that they simply copied their cousins.

“These results imply that Neanderthals were not apart from these developments,” says Zilhao. “For all practical purposes, they were modern humans, too.”

The new studies raise another intriguing possibility, says Clive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar Museum: that the capacity for symbolic thought was already present 600,000 years ago in the ancestors of both Neanderthals and modern humans.

He agreed with Zilhao that the new study supports the idea that Neanderthals used language. In addition to the evidence of symbolic thought, researchers have also found that the inner ears of Neanderthals were tuned to the frequencies of speech, much like our own.

“We don’t know how they spoke or what they said,” says Finlayson. “But they had the ability of speech.”

The cave paintings that Pike and his colleagues have dated are generally abstract. There’s no evidence so far that Neanderthals painted images of lions and other animals, as modern humans did thousands of years later.

But Pike doesn’t think a lack of animal imagery marks a mental deficiency in Neanderthals. It could simply reflect a cultural preference.

“It could just be that they had a different belief system and didn’t think animals were important to depict in deep caves,” he says. “If you have to prepare your pigment and get to a place in the pitch dark to paint a red line, that’s as meaningful as someone painting a bison.”

In the past, many researchers have claimed that mental differences between modern humans and Neanderthals were the reason we are alive today and Neanderthal populations have vanished. Our own ancestors, it’s been argued, were able to come up with creative solutions for survival.

The accumulating evidence puts Neanderthals on a more equal footing.

Their culture developed in parallel with that of modern humans in Africa. And their disappearance is not evidence of inferiority, only of the inexorable mechanics of evolution.

“Neanderthals have disappeared,” says Zilhao. “So have Fuegian Indians. So have Greenland Vikings. Population extinction has been a part of human history forever.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments