British Museum uses CT scans to show mummies' faces after thousands of years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The British Museum has turned to the latest technology to unlock the secrets of its mummies, one of the institution’s most popular visitor attractions, along visitors to explore cases that have remained closed for centuries.

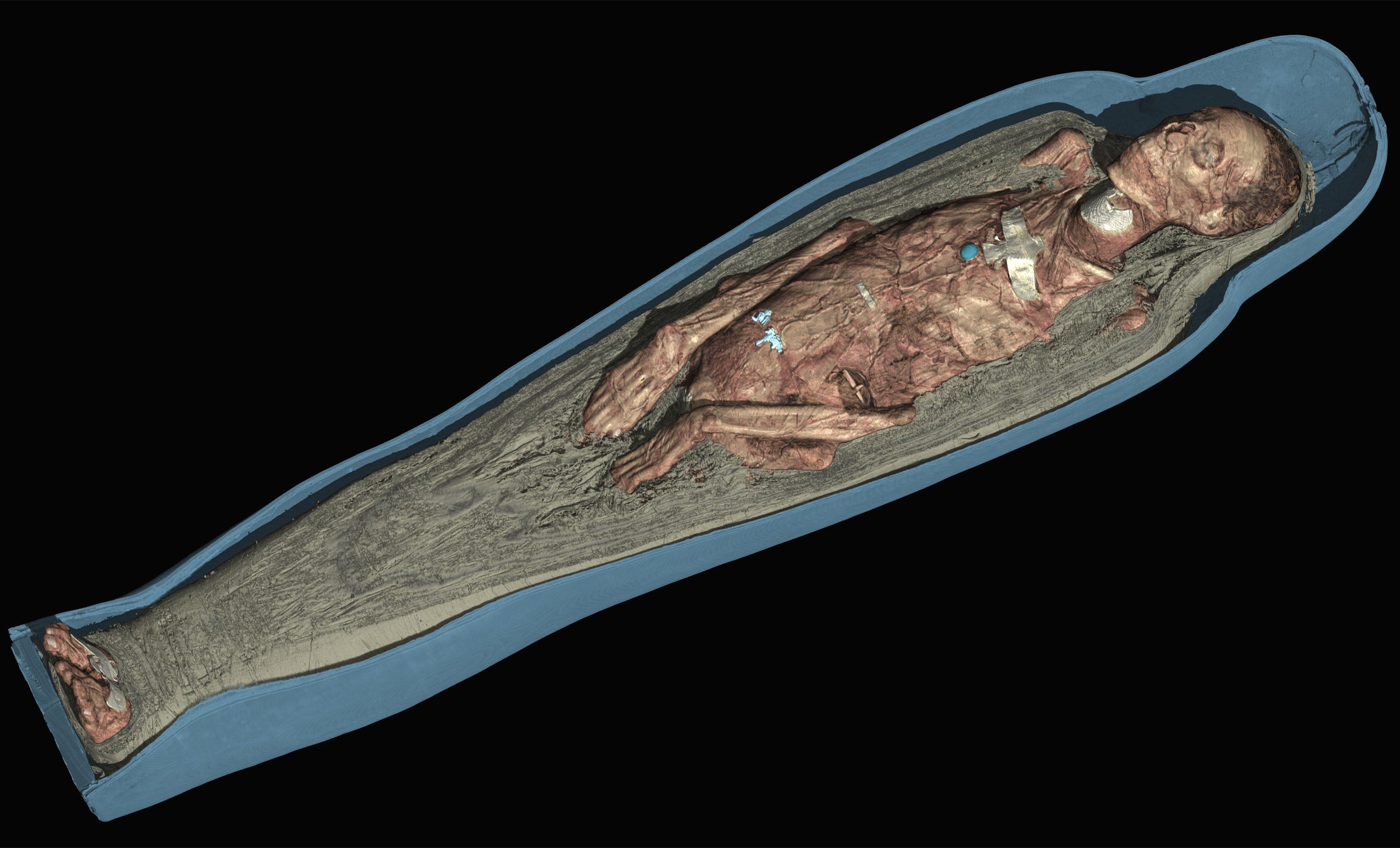

The analysis with cutting edge CT scanners has revealed the faces of some of the mummies for the first time, including that of a chantress from the Temple of Karnak, and has given valuable insights into the embalming and burial processes. All without opening the cases and disturbing the bodies.

A major new exhibition, "Ancient lives, new discoveries", opens next month and will tell the story of eight mummies from the Museum’s collection of 120 from ancient Egypt and Sudan.

Interactive screens will allow visitors to explore inside the cases, unwrapping the bodies and offering a closer than ever look at the remains.

Neil MacGregor, director of the British Museum, said: “Why is it from the age of six we are all fascinated by the mummies? It’s universal. It is the fact that the body can physically survive over 5,000 years. And it’s exciting being physically close to someone of long ago.”

The cases were taken to several hospitals including the Royal Brompton, where they were scanned.

“The scans build 3D models of the mummies and look at those with incredible clarity of detail,” curator John Taylor said. “The CT scans allow us to go on a journey beneath the wrappings and beneath the skin to see everything inside.”

The results will allow visitors to understand the lives of those who have been mummified more than ever before.

Dr Taylor said: “We’ve learnt a huge amount within a few months about mummies some of which have been in the museums for over 100 years. We can see their faces, the objects inside, and work out their age at death and the illnesses they suffered from.”

The first mummy entered the museum’s collection in 1756 and none has been unwrapped in 200 years.

They were x-rayed in the 1960s and CT scanned three decades later. Yet the technology advances in medical science has now advanced to a level where CT scans can produce images of “unprecedented high resolution”.

The information can be recreated in the computer and 3D printed. In the exhibition a plastic replica of the jawbone of one of the mummies will be on display as will the amulets inside the casket of another.

The eight mummies were selected from a period of over 4,000 years from sites in Egypt and the Sudan to reveal “different aspects of living and dying in the ancient Nile Valley,” the curator said. The museum plans to scan all 120 of its mummies.

One man mummified around 600BC in Thebes was found to have multiple abscesses which would have left him in considerable pain and may even have contributed to his death. “We don’t know his name,” Dr Taylor said. “He would have been a person of high status.”

The most extraordinary discovery was that the spatula used to scoop the brain through the nose in the mummification process had snapped off in his skull and was picked up by the scanner.

Dr Taylor said: “The tool in the back of the skull was quite a revelation as embalmers tools are something we don’t know much about. Very few can be identified. To find one inside a mummy is an enormous advance. That was an important find.” They now plan to recreate and print the tool using 3D printing technology.

The exhibition will also feature a female singer called Tamut, from Thebes in around 900BC, who was given the highest level of mummification available at the time.

Dr Taylor said that from inscriptions on the case it was clear she was a chantress in the Temple of Karnak. The researchers used the technology to find out the age of the mummies when they died by imaging the pelvis. Tamut was “at least in her 30s or 40s”. They found the sex of other mummies and pathological conditions they suffered.

The scans show how well preserved her skin and hair is, and gives visitors the first ever look at her face. It also found how amulets and other trappings were placed on the body. It was revealed that she had considerable plaque in her arteries which may have been responsible for her death.

Daniel Antoine, curator of physical anthropology at the British Museum, said getting ever closer to the mummies “feeds the public’s imagination. It’s a remarkable privilege to see someone’s face from the past.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments