Emperor Caligula’s ‘Floating Palace’ mosaic finally returns home

A 2,000-year-old artefact that had ended up in the home of a Manhattan antiquities dealer is now in an Italian museum, writes Elisabetta Povoledo

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If stones could speak, the mosaic unveiled recently at an archaeological museum just south of Rome would have quite the tale to tell.

It was crafted in the first century for the deck of one of two spectacularly decorated ships on Lake Nemi that the emperor Caligula commissioned as floating palaces. Recovered from underwater wreckage in 1895, the mosaic was later lost for decades, only to re-emerge several years ago as a coffee table in the living room of a New York City antiques dealer.

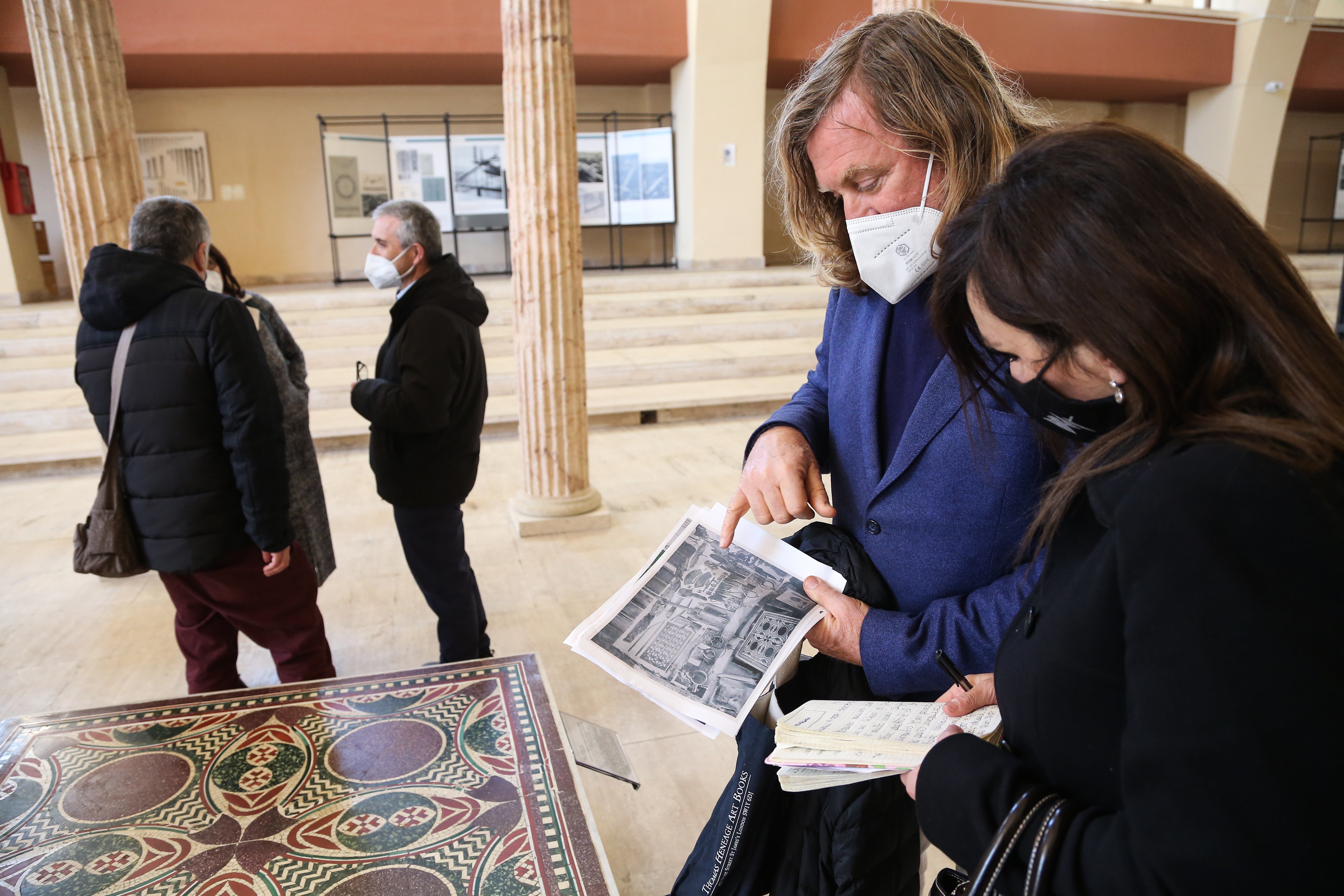

“If you look at it from an angle, you can still see traces of a ring from a cup bottom,” said Daniela De Angelis, director of the Museum of the Roman Ships in Nemi, referring to the piece’s modern use. The mosaic has been installed in the museum next to two other marble fragments salvaged from Caligula’s ships and was put on display on 11 March.

Read More:

“For us, it’s a great satisfaction today to see the mosaic in this museum,” said Major Paolo Salvatori of Italy’s elite art theft squad, whose investigations led to the mosaic’s return. “Bringing back cultural artefacts to their original context” is the ultimate goal of the squad, he said, and the recovery of the mosaic reflected cooperation among the squad, Italy’s cultural authorities and law enforcement in the United States.

Caligula’s rule only lasted from AD 37 to 41, but he enthusiastically embraced the trappings of the position, including an opulent residential compound on the Esquiline Hill in Rome, a villa on the southwest shore of Lake Nemi and the two ships.

“They were floating palaces,” whose “aquatic luxury” was likely inspired by a renowned barge used by Marc Antony and Cleopatra on the Nile, said Massimo Osanna, director general of Italy’s national museums.

Scholars are unsure whether the ships had a specific purpose, although some have posited that one was used for the worship of the Egyptian goddess Isis. In any case, Caligula did not skimp on the ships’ decor, which included mosaics on the walls, intricately inlaid marble floors, decorated fountains and marble columns. Bronze figures decorated the beams, headboards and other wooden parts.

If ancient sources are to be believed, Caligula was a deranged and despotic ruler with a voracious sexual appetite and a vicious streak of cruelty, but modern scholarship has thrown doubt on those accounts.

In all likelihood, the fire that destroyed the two ships was caused by a deliberate choice on the part of the German soldiers

“There’s a lot of fake news about Caligula,” said Barry Stuart Strauss, a professor of history and classics at Cornell University. “I don’t want to make him out to be a nice guy or something,” he said, because Caligula executed a number of senators, had a sharp tongue and made many enemies. And when Caligula was assassinated in AD 41, “it wasn’t difficult to find people who wanted to assassinate him”, Strauss added. “But we can’t trust the myths.”

With Caligula’s death, the ships were destroyed and sank to the bottom of the lake. Various attempts to raise them over the centuries were unsuccessful as well as damaging, and the wrecks were repeatedly plundered, De Angelis said.

In 1895, antiquarian Eliseo Borghi managed to recover part of the ship’s decorative bounty, including some of the bronze decorations and parts of the marble floor. These items – including the recently returned mosaic, which he had restored using fragments of ancient marble integrated with modern pieces – were sold to museums in Italy and elsewhere in Europe as well as to private collectors.

The location of the deck mosaic would have likely remained unknown had it not been for the 2013 presentation in New York of a book by an Italian marble expert, Dario Del Bufalo, on the use of red porphyry in imperial art. He happened to show a photograph of the missing mosaic.

“That’s Helen’s table,” Del Bufalo recalled one of the attendees exclaiming. Helen turned out to be Helen Costantino Fioratti, president of L’Antiquaire and the Connoisseur, a Manhattan fine art and antiques gallery.

Del Bufalo said that he had assisted Italy’s art theft squad in identifying Fioratti’s mosaic as the section of the marble floor restored by Borghi. The piece was seized by US authorities in 2017 and returned to Italy. Fioratti said at the time that she and her husband had bought the mosaic in good faith, in the late 1960s, from a member of an aristocratic family.

“She cared a lot about that table,” Del Bufalo said on the opening day of the exhibition. He said that the marble had been seized because Fioratti could not prove that it had been legally exported to the United States. She was never charged with any crimes in Italy.

Caligula’s ships were finally recovered between 1929 and 1931, after the lake was drained, an enterprise that exemplified “the highest feat of Italian hydraulic engineering,” said Alberto Bertucci, mayor of Nemi, which is arguably better known for its strawberries than its archaeological heritage.

The Nemi museum was specially designed in the 1930s to house the massive ships – which measured roughly 240 feet long and 78 feet wide – as well as other artefacts dredged up at the time, including fragments of mosaics and brass tiles that covered the roof of a structure on one of the ships.

But on the night of 31 May 1944, the ships were destroyed by a fire that scholars believe was deliberately set by vengeful German troops.

“There was little left afterward because the fire was devastating,” De Angelis said. But some artefacts survived because they had been sent to Rome for safekeeping.

“The fire in the museum was ignited to destroy, and it did not disappoint,” said the Reverend John McManamon, a visiting scholar at the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University, who has written a book on the ships that is scheduled to be published next year. McManamon’s research backed the conclusions of a 1944 investigative commission that found that “in all likelihood, the fire that destroyed the two ships was caused by a deliberate choice on the part of the German soldiers”, he wrote in an email.

Read More:

Bertucci said he had initiated discussions with Italy’s Foreign Ministry about demanding compensation from the German government for the destruction of the ships. Any money received would be used to build scale models of the ships and to “return to humanity what was lost,” he said in an interview earlier this month.

“Today is a very important day,” De Angelis said at the mosaic unveiling. “Visitors to the museum will find a new addition in its natural place, alongside other marble fragments from the ship, as if it had never been away.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments