Bizarre species found preserved in fool’s gold reveals the secrets of scorpions

There are more species of arthropod than any other group of animals on Earth – we know now more about their history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A 450-million-year-old fossil of an ancient relative of spiders found in fool’s gold could shed light on how scorpions for their pincers.

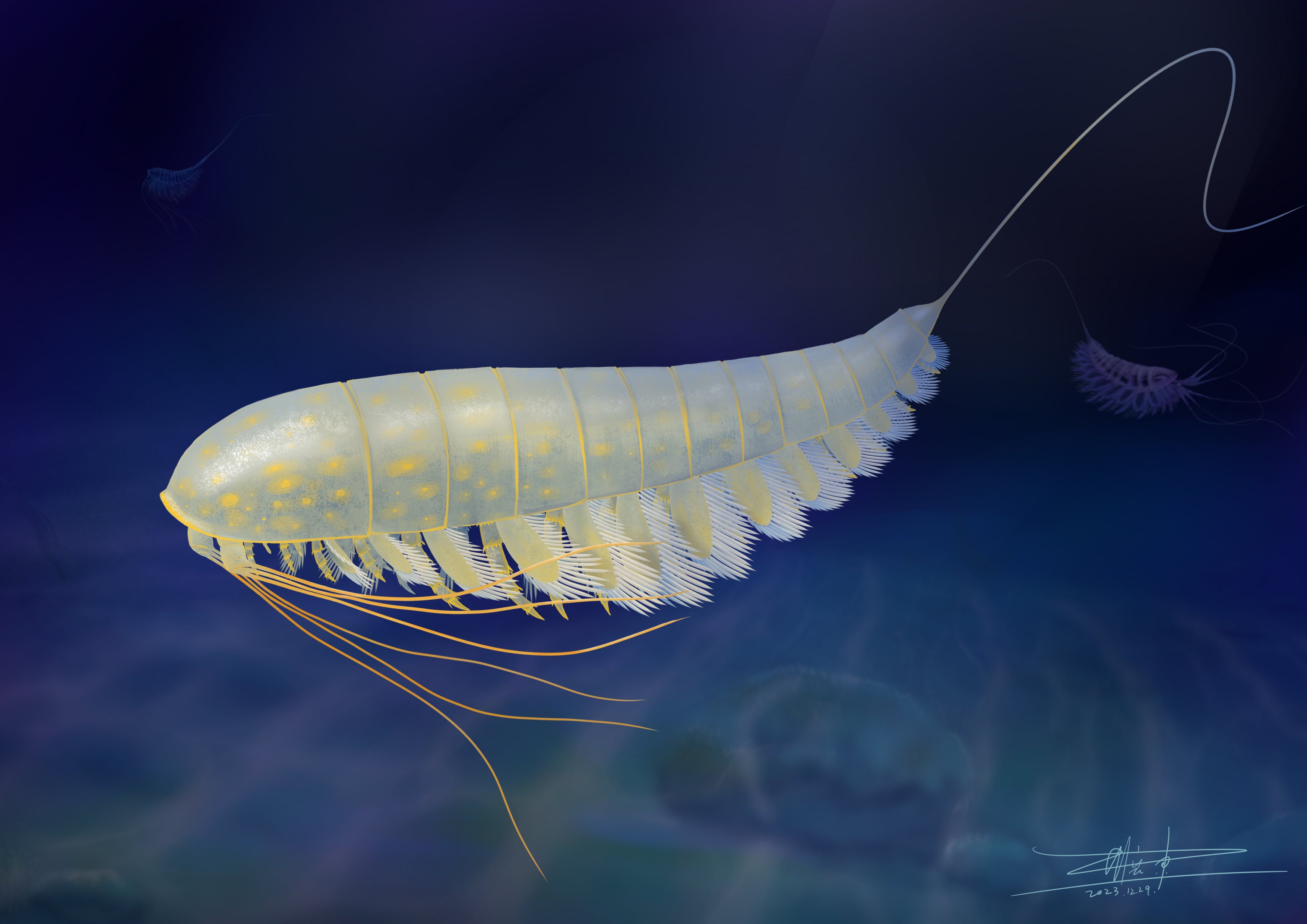

A newly discovered species has been called Lomankus edgecombei, and is distantly related to scorpions and horseshoe crabs.

Named after arthropod expert Greg Edgecombe, the fossil belongs to a group called megacheirans, a group of arthropods with a large, modified leg (called a great appendage) at the front of their bodies that was used to capture prey.

Experts suggest it sheds light on the long-standing riddle of how arthropods evolved the appendages on their heads.

These body parts can include the antennae of insects and crustaceans, and the pincers and fangs of spiders and scorpions.

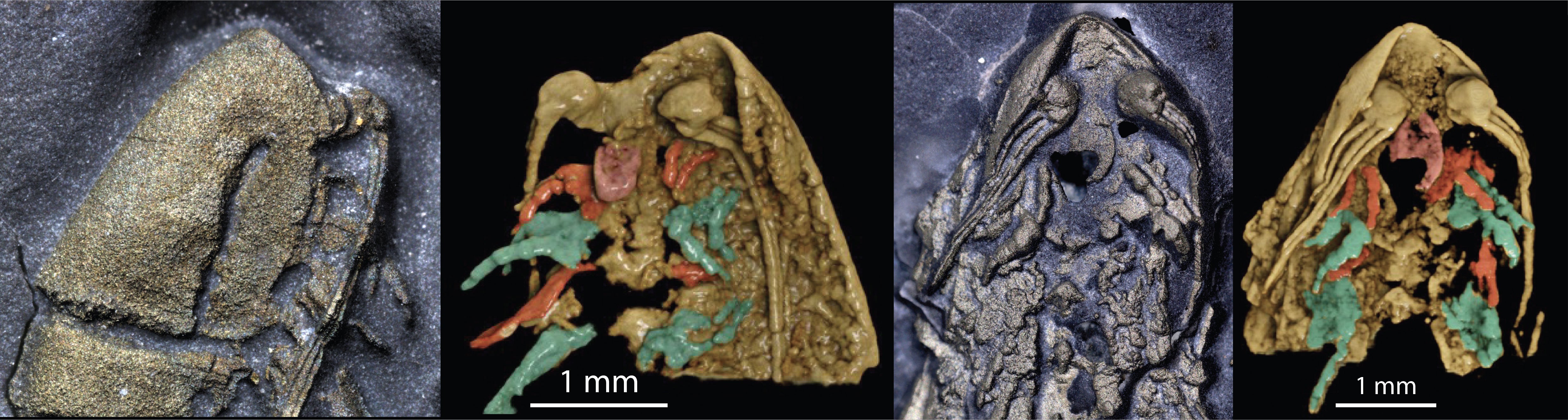

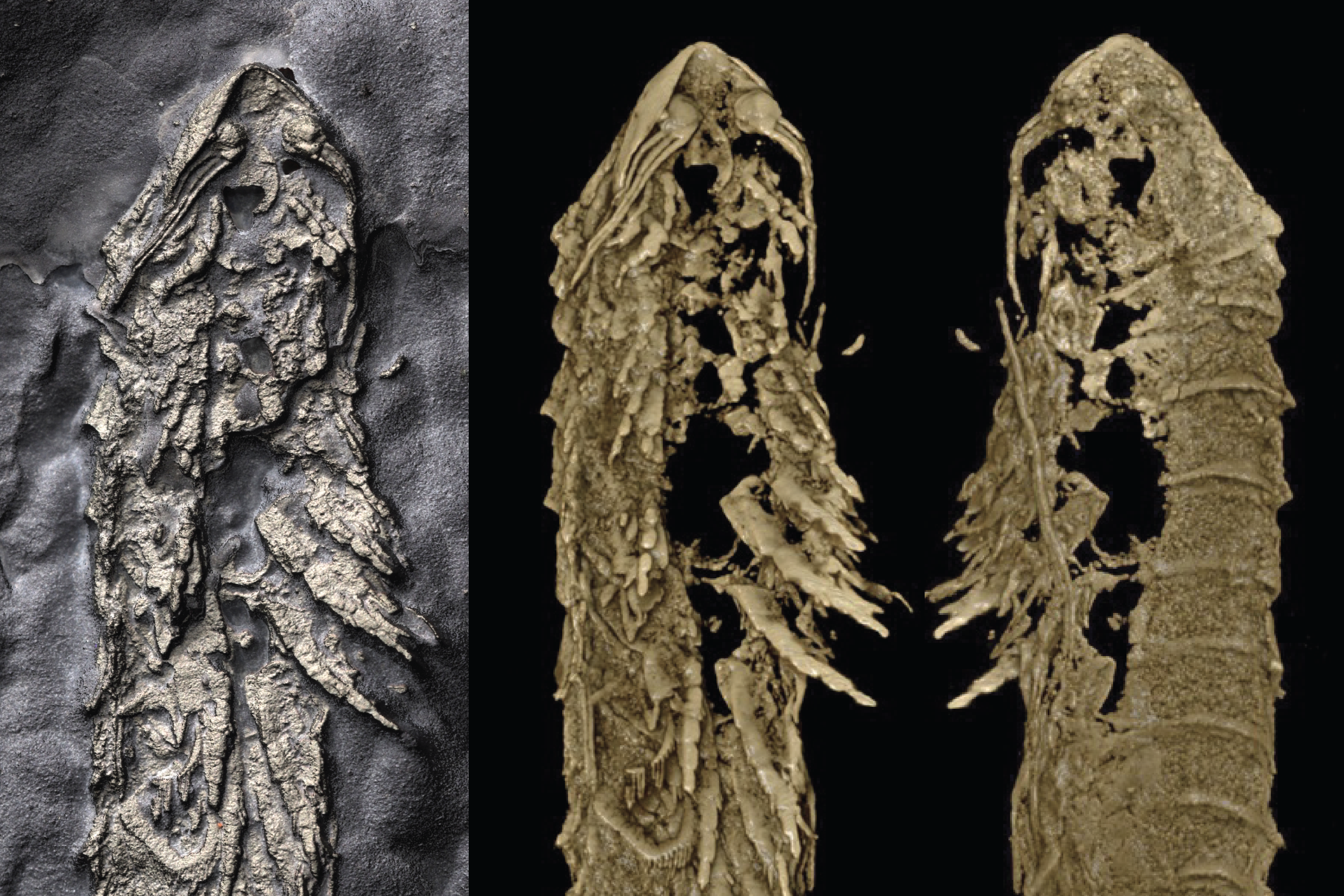

A team of researchers was led by Associate Professor Luke Parry, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, who said: “As well as having their beautiful and striking golden colour, these fossils are spectacularly preserved.

“They look as if they could just get up and scuttle away.”

Megacheirans like Lomankus were very diverse during the Cambrian Period some 538-485 million years ago, but they were thought to be largely extinct by the Ordovician Period (485-443 million years ago).

Experts suggest the discovery sheds light on the long-standing riddle of how arthropods evolved the appendages on their heads.

These body parts can include the antennae of insects and crustaceans, and the pincers and fangs of spiders and scorpions.

The flexible, whip-like hairs at the front of the Lomankus claws suggest the creature was using this frontal appendage to sense the environment, rather than to capture prey.

This indicates that it lived a lifestyle very different from its more ancient relatives in the Cambrian Period.

“Today, there are more species of arthropod than any other group of animals on Earth.

“Part of the key to this success is their highly adaptable head and its appendages, that has adapted to various challenges like a biological Swiss army knife”, said Associate Professor Parry.

According to the study published in Current Biology, unlike other megacheirans, Lomankus seems to lack eyes, suggesting that it relied on its frontal appendage to sense and search for food in the dark, low-oxygen environment in which it lived.

The fossil offers new clues towards solving the highly-debated question of what the equivalent of the great appendage of megacheirans is in living species.

Co-corresponding author Professor Yu Liu, Yunnan University, China, said: “These beautiful new fossils show a very clear plate on the under side of the head, associated with the mouth and flanked by the great appendages.”

These features are similar to living arthropods, suggesting the great appendage is the equivalent of the antenna of insects and the mouths of spiders and scorpions, researchers say.

The fossil was found at a site in New York State, in the US, that contains the famous Beecher’s Trilobite Bed, a layer of rock containing multiple well-preserved fossils.

The animals preserved in Beecher’s Trilobite Bed lived in a hostile, low oxygen environment that allowed iron pyrite, commonly known as fool’s gold, to replace parts of their bodies after they were buried, resulting in golden 3D fossils.