Archaeologists reveal method used by ancient humans to hunt mighty mammoths to extinction

Prehistoric hunters used stone-tipped spears as pikes to kill charging mammoths and mastodons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Early humans in North America hunted mammoths to near extinction by using their spears as pikes planted in the ground rather than as throwing weapons as previously thought, according to a new study.

Among the most frequently unearthed artefacts from archaeological sites in North America dating back 13,000 years are Clovis points, which are sharpened tips made by shaping rocks like chert, flint or jasper.

The special weapons, named after the New Mexico town where they were first discovered, range in size from a person’s thumb to an iPhone. They have a distinct, sharp edge with fluted indentations on the base.

Clovis points have been found across Ice Age sites in America, some lodged in mammoth skeletons. Exactly how early humans used these sharp weapons has been a subject of debate.

Some theories suggested that the special tips were attached to spears to surround and jab mammoths while others suspected that they were used to scavenge wounded animals.

There were a limited number of suitable rocks that could be fashioned into such spears, though, so scientists reasoned that early humans could not have risked throwing or carelessly using these weapons. Experiments also hinted that stone-tipped spears shot at mammoths might have felt no more than pinpricks to the beasts, which weighed upto nine tonnes.

The new study, published on Wednesday in the journal PLoS One, demonstrates that hunters likely braced the spears against the ground and angled the Clovis points upwards, like a pike, to impale the charging mammoths.

“The kind of energy that you can generate with the human arm is nothing like the kind of energy generated by a charging animal. It’s an order of magnitude different,” study co-author Jun Sunseri said.

Such a technique was popular in battles for stopping horses but there was no evidence it was used before the advent of metal weapons.

Researchers said force from this planted pike set-up would have driven the spears deeper into the prey’s body, causing more damage than the strongest prehistoric hunter.

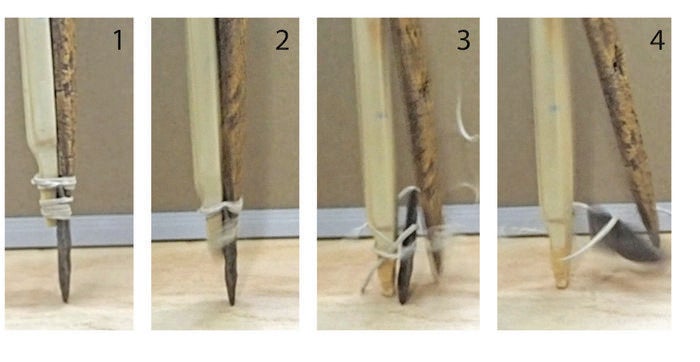

In the study, scientists reviewed historical anecdotes about people hunting with planted spears and conducted an experimental study of stone weapons used as pikes.

They built a test platform to assess how the spear system reacted to the simulated force of an approaching animal and measured the force they could withstand before the Clovis point snapped.

Once sharpened rocks attached to such a mounting system pierced an animal, scientists found that the tips functioned like modern-day hollow-point bullets capable of inflicting “serious wounds” to mastodons, bison and saber-toothed cats.

“This ancient Native American design was an amazing innovation in hunting strategies. This distinctive Indigenous technology is providing a window into hunting and survival techniques used for millennia throughout much of the world,” study co-author Scott Byram said.

Researchers said the Clovis tip is testament to the ingenuity of early Indigenous people in cohabitating the frigid landscape with now-extinct megafauna like mastodons and mammoths.

“Unlike some of the notched arrowheads, it was a more substantial weapon. And it was probably also used defensively,” Dr Byram said.

“These spears were engineered to do what they’re doing to protect the user,” Dr Sunseri added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments