Curly hair allowed early humans to ‘stay cool and actually conserve water’

‘We think scalp hair provided a passive mechanism to reduce the amount of heat gained from solar radiation’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Curly hair may have been an adaptation in early humans that helped them stay cool while conserving water, according to a new study.

The research, published on Thursday in the journal PNAS, sheds more light on how the evolutionary adaptation of hair texture may have enabled human brains to grow to modern-day sizes.

Scientists, including those from Penn State, studied the role human hair textures play in regulating body temperature.

“Humans evolved in equatorial Africa, where the sun is overhead for much of the day, year in and year out,” study co-author Nina Jablonski from Penn State said in a statement.

“Here the scalp and top of the head receive far more constant levels of intense solar radiation as heat. We wanted to understand how that affected the evolution of our hair. We found that tightly curled hair allowed humans to stay cool and actually conserve water,” Dr Jablonski explained.

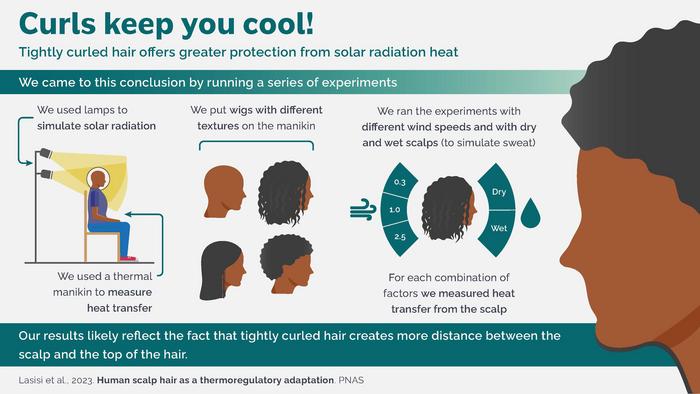

Researchers used a thermal manikin – a human-shaped model that uses electric power to simulate body heat.

This set up allowed them to study heat transfer between human skin and the environment, as well as from human hair wigs, to examine how diverse hair textures affect heat gain from solar radiation.

Scientists programmed the manikin to maintain a constant surface temperature of 95F (35C), similar to the average surface temperature of skin, and set it in a climate-controlled wind tunnel.

They took base measurements of body heat loss by monitoring the amount of electricity required by the manikin to maintain a constant temperature.

Researchers then shined lamps on the manikin’s head to mimic solar radiation under four scalp hair conditions – none, straight, moderately curled and tightly curled.

They estimated the difference in total heat loss between the lamp measurements and the base measurements to determine the influx of solar radiation to the head.

Heat loss at different windspeeds and after wetting the scalp to simulate sweating was also calculated.

All of this helped scientists model how diverse hair textures would affect heat gain in 86F (30C) heat and 60 per cent relative humidity – similar to the environments in equatorial Africa.

While all hair was found to reduce solar radiation to the scalp, tightly curled hair provided the best protection from the sun’s radiative heat while minimising the need to sweat to stay cool.

As early humans began walking upright in equatorial Africa, researchers said the tops of their heads increasingly bore the brunt of solar radiation.

Studies have shown that the brain is sensitive to heat and the larger it grows, the more heat it generates, with too much of it likely to cause heat stroke.

While humans developed sweat glands to efficiently keep cool, sweating comes at the cost of losing water and electrolytes.

Based on the latest study, scientists suspect scalp hair likely evolved as a way to reduce the amount of heat gain from solar radiation, thereby keeping humans cool without having to lose electrolytes and water.

“Around 2 million years ago we see Homo erectus, which had the same physical build as us but a smaller brain size. And by 1 million years ago, we’re basically at modern-day brain sizes, give or take,” said Tina Lasisi, another study author.

“Something released a physical constraint that allowed our brains to grow. We think scalp hair provided a passive mechanism to reduce the amount of heat gained from solar radiation that our sweat glands couldn’t,” Dr Lasisi explained.

The research provides preliminary evidence that can improve our understanding of how human hair evolved.

Studies done on skin colour and how melanin protects people from solar radiation have helped shape some decisions on the amount of sunscreen needed in certain environments.

Similarly, the new findings can help understand if a certain hair type may be better suited to thrive in specific conditions.

“When you think about the military or different athletes exercising in diverse environments, our findings give you a moment to reflect and think: is this hairstyle going to make me overheat more easily? Is this the way that I should optimally wear my hair?” Dr Lasisi explained.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments