Archaeologists discover 10,000-year-old rice beer recipe in China

Findings highlight broader cultural environment in which early rice agriculture developed in Asia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of rice beer dating back about 10,000 years at a site in Eastern China, providing further insights into the origins of alcoholic beverages in Asia.

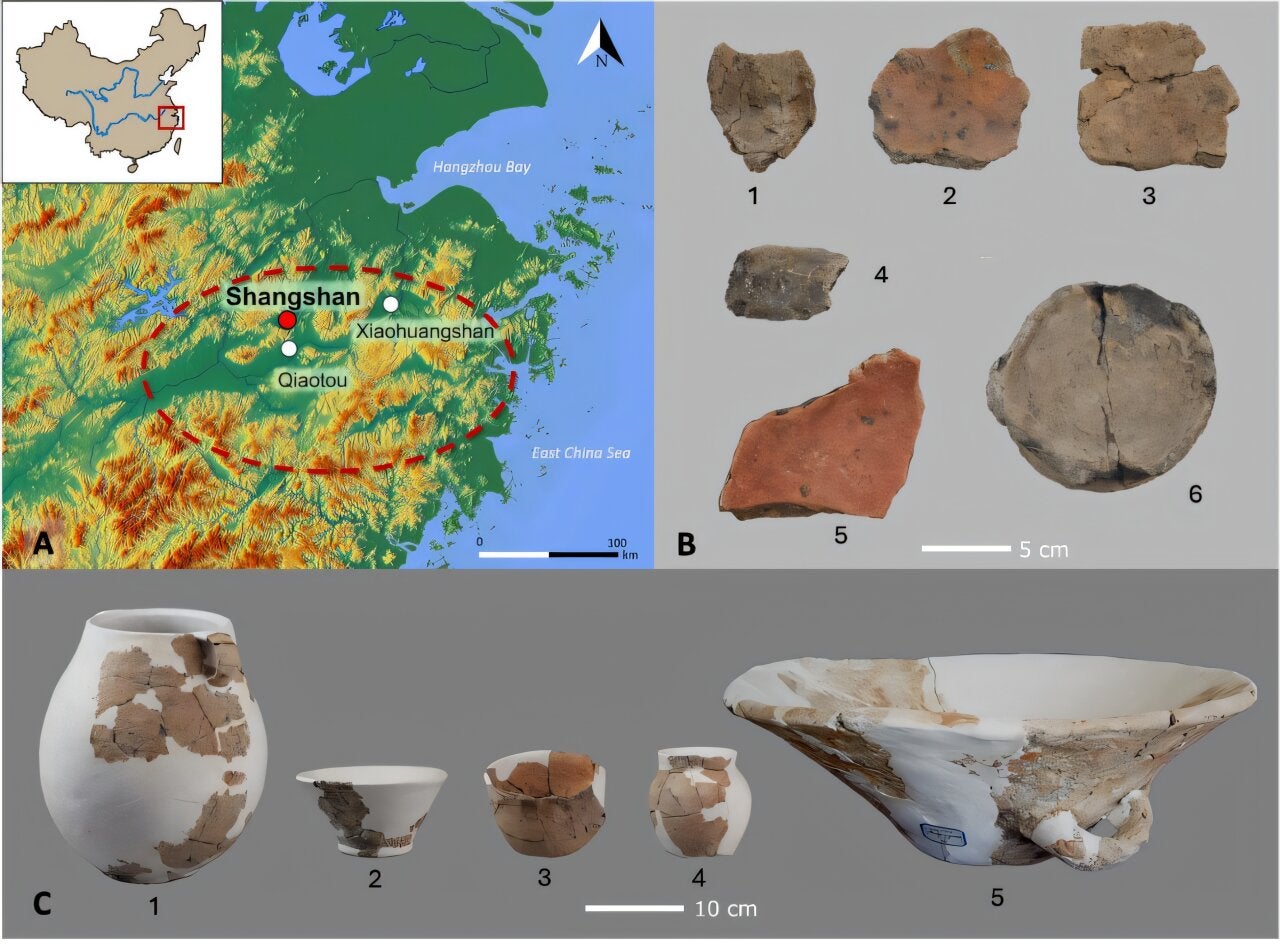

The discovery at the Shangshan archaeological site in China’s Zhejiang Province unveils the cultural and environmental context of the practice of rice fermentation in the region as well as the broader development of early agriculture in Asia.

In the research, published in the journal PNAS on Monday, scientists twelve pottery sherds from the early phase of the Shangshan site dating to about 10,000 years ago.

“These sherds were associated with various vessel types, including those for fermentation, serving, storage, cooking, and processing,” study co-author Jiang Leping from China’s Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (ICRA) said.

Researchers analysed residues from the inner surfaces of the pottery as well as the pottery clay and sediments in their surroundings.

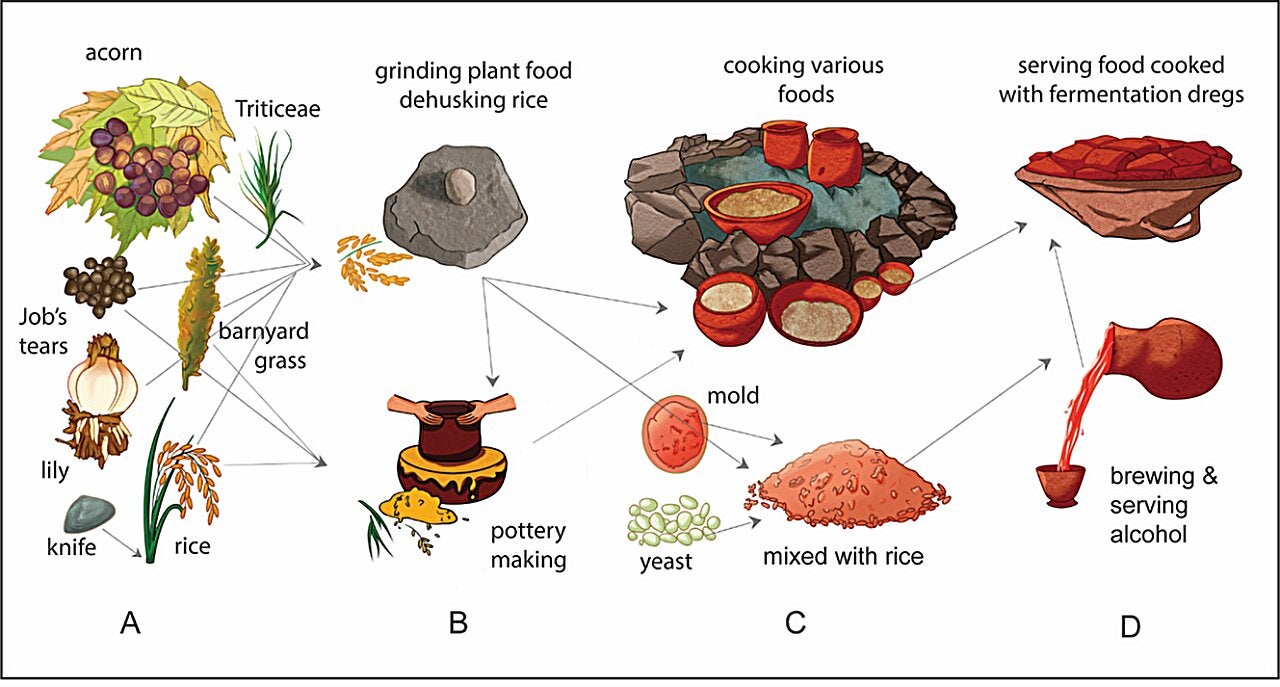

They particularly focussed on identifying the source of tiny plant fossil remains, starch granules, and fungi in these samples, revealing insights into the pottery’s uses and the food processing methods used by the ancient people of the time.

A “significant presence” of domesticated rice fossil remains was found in the pottery residues as well as tiny fossils of starch granules, Job’s tears, barnyard grass, Triticeae, acorns, and lilies, scientists said.

“This evidence indicates that rice was a staple plant resource for the Shangshan people,” Dr Leping said.

Archaeologists also found that rice husks and leaves were used in pottery production, demonstrating the integral role of rice in ancient Chinese culture.

The starch granules, scientists noted, showed signs of degradation and gelatinisation by enzymes, processes characteristic of fermentation.

They also found moulds and yeast cells, some of which are typically used as starters in traditional brewing methods.

These fungi remains, according to scientists, showed developmental stages typical of fermentation.

The fungal residues were found to be particularly in higher concentrations in globular jars compared to other different pottery vessel types uncovered at the site.

This suggests vessel types used by the ancient culture were closely linked to specific functions, and the globular jars may have been purposely produced for alcohol fermentation.

Researchers also analysed sediments from the site as control samples, which were found to have significantly fewer starch and fungal remains than pottery residues.

Overall, these findings confirm that the pottery residues were directly linked to fermentation activities.

The research highlights the emergence of brewing technology in the early Shangshan culture as closely linked to rice domestication and the period’s warm and humid climate.

“Domesticated rice provided a stable resource for fermentation, while favourable climatic conditions supported the development of qu-based fermentation technology, which relied on the growth of filamentous fungi,” Liu Li, another author of the study, said.

“These alcoholic beverages likely played a pivotal role in ceremonial feasting, highlighting their ritual importance as a potential driving force behind the intensified utilization and widespread cultivation of rice in Neolithic China,” Dr Li said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments